Capitalism, Slavery, and the Industrial Revolution

The Williams Thesis, Part I

This post is intended to be the first installment of a trilogy. Part I, below, covers the debate up to the late 1980s. The second will run through debates among economic historians since 1990, focusing especially on exchanges between Harley, Findlay and O’Rourke, McCloskey, and Zahedieh. The last will survey research in economics on the Atlantic economy and slave trade up to the present.

This series is not about the economics of plantation slavery, which was brutal, profitable, and fully compatible with capitalism. It’s about the role that slavery played in endogenously generating modern growth in Britain. With that in mind, the TL;DR:

Profits from the slave trade were not demonstrably large compared with British national income.

While they were pretty big compared with industrial investment, supposing them to be significant requires implausibly assuming that all profits were saved and that all profits went into industry, rather than land or trade/services.

The Jamaican plantation economy did generate substantial wealth, but for the same reasons in (2) it’s not clear that they actually financed much investment. Many Jamaican planters repatriating money to Britain did what you’d expect them to do—buy estates.

Moreover, it’s possible that the wealth generated by the Jamaican plantations was completely offset by A) elevated sugar prices due to mercantilist tariffs and B) the costs of Jamaica’s garrisons and naval defense.

Debating Williams’ financing channel was unlikely to prove fruitful anyway; capital accumulation probably did not cause British industrialization, given the modest set-up costs of even large factories.

By the 1980s, most pro-Williams historians had given up on fighting about “small ratios” in favor of an “Atlanticist” view emphasizing British exports to New World plantation economies rather than investment capital; this view was more or less accepted by several anti-Williams historians.

In August 1962, an Oxford historian became the first Prime Minister of a newly independent Trinidad and Tobago. He was the country's only Prime Minister until 1981, winning an unbroken string of elections up to his death at the age of 69, by which time he’d been dubbed the “Father of the Nation.”

Among economic historians, Eric Williams is better known for his 1938 Ph.D. thesis, published in 1944 as Capitalism and Slavery. Williams, a Marxist, argued that slavery catalyzed British industrialization during the 18th century and that "the monster [capitalism] then turned around and destroyed its progenitors [slavery]"—manufacturers no longer needed the West Indian plantations and abolished an obsolete slavery. Williams wanted to show that abolitionism played a minor role in emancipation (the Marxist elevation of the material over the ideological). But economic historians have mostly focused on his preliminary claim, which we now call the "Williams thesis": that Britain's involvement in the slave-based Atlantic economy caused the Industrial Revolution.

For a short book, Capitalism and Slavery ranges over an enormous variety of topics, so it's hard to pick out the core tenets of the “Williams thesis,” other than the basic association between slavery and British industrial development. Williams focused on surplus capital, drawing a channel from profits derived in the Atlantic trade and the plantation economy to investment: "the profits obtained provided one of the main streams of that accumulation of capital in England which financed the Industrial Revolution" and "supplied part of the huge outlay for the construction of the vast plants to meet the needs of the new productive process and the new markets."

Capitalism and Slavery was, as Kenneth Morgan (2000) charitably suggests, written "at a time when statistical presentation in economic history was much less rigorous than today." He means that Williams' approach was scattershot. I've isolated three parts of the original Williams thesis: 1) that profits from the slave trade were an irreplaceable source of industrial finance 2) that the wealth of Caribbean planters played a similar role 3) that the Atlantic economy was, in general, important for British development. To support 1), Williams pushed a 30 percent figure for profits on the slave trade, which would have been more than twice the "normal" rate for the day. His data was totally inadequate for the purpose, consisting largely of lists of rich Britons who'd somehow made at least a pound or two off slavery. So there was a lot of room for early cliometricians—who cut their teeth with controversial debunkings of historical theories—to challenge his expansive claims.

The Williams thesis is economic history's longest-running debate. And because slavery is often perceived as capitalism's original sin, it just won't go away. Williams has been revived in the twenty-first century by the popular book Power and Plenty by Ronald Findlay and Kevin O'Rourke, as well as recent interventions by economists Stephen Redding, Stephen Heblich, and Hans-Joachim Voth. We're starting in 1944, and with almost eighty years of terrain to cover, we're going to have to split this up into three posts. The first will tackle the initial (and heated) debates over points 1) and 2), ending with the work of Barbara Solow in the late 1980s. The second will explore the economic history literature since Solow, focusing on the evolution of the Williams thesis to cover broader assertions of the importance of the Atlantic economy (3). The third and final version will survey the recent work of economists in raising the ghost of Williams in a new conceptual garb, based on models of agglomeration economies and financial frictions.

The trade profits and plantation wealth debates happened sort of simultaneously, so we'll weave between them as we go. What we'll see is that the original formulation of the Williams thesis was basically completely wrong, and by the early 1980s that had become pretty obvious. But a revived version, emphasizing the importance of the broader “Atlantic system” to British industrialization, had replaced the old profits contretemps and become orthodox by 1987.

Slave Trade Profits

At the core of the Williams thesis is an argument that profits from the slave trade launched British industrialization by contributing to capital formation. This claim rests on answers to three empirical sub-questions: 1) how big were the profits relative to other industries and the overall size of the economy? 2) did profits rise prior to industrialization? 3) did slave trade profits specifically make a difference? The first phase of the debate centered on 1). Williams himself attempted no real analysis of systematic profits, instead adducing specific instances in which slave traders had reaped enormous gains—like John Tarleton, who’d turned £6,000 in 1748 into almost £80,000 by 1783. As I noted above, Williams guessed that average profits were 30 percent. As his detractors showed, he was totally wrong.

The first critiques of Williams' profit-based arguments came from Bradbury Parkinson (1951), an accountant, who demonstrated how to actually read slavers' account books. In Hyde et al. (1952), he and two co-authors showed that outcomes for Liverpool slave traders were highly varied, ventures were risky, and partnerships broke up frequently, all of which lowered returns. The main series used for this project, the 1757-84 accounts of William Davenport, was later studied by David Richardson (1975). Richardson disaggregated the 67 extant voyage accounts in the Davenport records and found that 49 were profitable and 18 were losses. Moreover, he found that the average profit was 8.1 percent per annum, substantially lower than Williams' back-of-the-napkin estimate.

Roger Anstey's The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition, 1760-1810 sought to extend the profit analysis beyond single voyages in a constricted time period. He matched data from the voyage accounts to the numbers and prices of slaves sold in the Americas, concluding that profits rose from 8.1 percent in 1761-70 to 13.4 percent in 1781-90 before falling back to 3.3 percent in 1801-7. The average annual profit during those fifty years was 10.2 percent, slightly higher than Richardson's figure, but still much lower than Williams'.

Thomas and Bean (1974) devised a third and final approach to minimizing the profits of the slave trade, which was to theoretically examine the market structure of each stage in the transport of slaves from Africa to America. Since all stages of the commerce open to Europeans could be freely entered, they argue that levels of competition were extremely high and that all inputs but the slaves themselves were supplied perfectly elastically. So marginal firms should only have experienced temporary periods of non-zero profits. In a phrase that must have annoyed the heck of their adversaries, Thomas and Bean write that "[t]he 'invisible hand' eliminated any long-run economic profits." Indeed, the potential profits were actually passed on to the African slavers—the "fishers of men"—themselves.

Stanley Engerman (1972) asked the macro-question (3): "to what extent was the over-all level of investment in society raised by the profits of the slave trade?" Engerman noted that Williams' model, unlike his own neoclassical "new economic history" reasoning, assumed that resources weren't fully employed; so Williams was led to count any resources (e.g. capital and labor used in shipping and on plantations) used in the slave trade as gains. His procedure is simple: count the number of slaves exported, estimate the profits per slave, multiply the two figures, and compare the result to the investment share of British national income.

Engerman's profit-per-slave figures were probably (intentionally, to bias the analysis against himself) gross overestimates, as he just subtracted 1/4 the Jamaica price to account for costs. Even using the overstated profit numbers, slave profits were usually less than .5% of British GDP, and less than .1% using Anstey's more accurate estimates. Assuming a 5 percent investment rate and that slave traders saved every penny of their returns, the slave trade contributed at most 10.8 percent of British capital formation at its peak and as little as 2.4 percent at its trough. Only if one assumes that A) Engerman's upper-bound estimates are correct B) all profits were saved and C) all saved profits went into industry do you get a significant outcome—that slave profits peaked at 54 percent of industrial and commercial capital formation. Using Anstey's empirically derived figures, however, Engerman comes out with a much smaller (but still inflated!) 7 percent. Anstey himself conducted a similar exercise three years later and found that profits from the slave trade accounted for .11 percent of national investment.

In short, the first wave of new economic history studies to tackle the slave trade portion of the Williams thesis effectively shattered it.

A Plantation Revolution?

Williams also alleged that the wealth of the Caribbean plantations, obviously derived from slavery, was a second source of funds for British industrialization. The West Indies were the richest part of the first British Empire, valued at £50-60 million in 1775 and £70 million in 1789. The region's population rose by 40 percent from 1750 to 1790, sugar production by 11 percent, and exports to Britain by 9 percent. Once again, Williams amassed examples, this time of conspicuously wealthy Jamaican planters who invested their savings in British industry. They included Richard Pennant, a Liverpool MP who put the proceeds from his 600-slave, 8000-acre plantation into slate quarries in North Wales, and the Fuller family, whose interests included Jamaican estates, charcoal ironworks, and gun foundries.

But Williams made too much of his already small sample. Richard Pares (1950) showed that William Beckford, a millionaire who owned 14 sugar plantations and over 1000 slaves, invested little of his vast wealth in British industry. Many others, like John Pinney, were content with channeling funds into government securities and land. It's also unclear how much Jamaican money came back to Britain; some historians have alleged that it only came back with emancipation, which would be far too late to play the role Williams allows it.

Richard B. Sheridan's "The Wealth of Jamaica in the Eighteenth Century" (1965) examined records of Jamaican inventories. They found that their average value rose from £3819 in 1741-5 to £9,361 in 1771-5, a movement almost entirely driven by increases in the number (2x) and price (+76%) of slaves. He valued Jamaica's sugar estates at £18 million sterling, which sent an annual income flow to absentee planters and merchants of £1.5 million—amounting to 8-10 percent of British national income. That would be quite a lot! But his analysis was, well, imperfect. Since Sheridan had no aggregate data on financial flows between the colonies and the capital, his line of argument is essentially that 1) planters were rich 2) riches were produced by slaves 3) that money must have gone back to Britain 4) especially into British industry and 5) that this funding proved the critical margin in establishing new enterprises. As you can tell, there are lots of assumptions here!

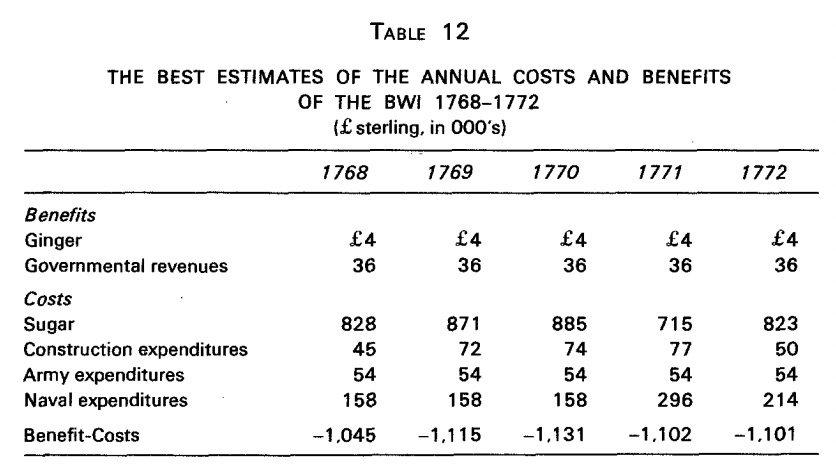

Surprisingly, Robert Thomas (1968) critiqued Sheridan's analysis without touching assumptions 1-5. Instead, he proposed a cost-benefit analysis of Britain's possession of the West Indies for the British consumer. Warships and garrisons were expensive (an average first-rate ship, in John Brewer's oft-quoted example, could cost 10 times a large factory), as were the preferential tariffs granted to Jamaican planters to protect the imperial sugar market. Thomas actually felt that Sheridan had underestimated the value of the West Indies, but that this was both totally irrelevant by comparison with Britain's overall wealth and a poor return on defense costs.

Thomas asks what the counterfactual return to investing this wealth (£37 million) gradually in the British economy might have been; picking out the lower-bound 3.5 percent rate on risk-free consols to bias his own estimate downward, the number to beat was £1.295 million. But Sheridan didn't account for the elevated prices that consumers paid for the discriminatory sugar tariff, which set consumers back £383,250 per annum, or the massive costs of defense (£115,000 on troops and £315,895 for ships). Deducting these sums from the annual total left only £660,750 in social return, or 2 percent per annum. By Thomas's logic, Britain would’ve had higher income by just buying riskless assets.

Sheridan (1968) replied that Thomas had overstated the size of the non-sugar staples sector and thus the wealth of Jamaica/the West Indies, artificially reducing the return on capital. He also adduced a list of "invisible" sources of profits like insurance, remittances via North America, bullion from the entrepot trade, and sales of Jamaican industry that altogether raised his rate of return to 8.4 percent, even including Thomas's cost deduction.

Coelho (1973), meanwhile, backed Thomas, arguing that the high import prices on Caribbean sugar diverted resources and defense costs drained £1.1 million per annum out of Britain. Capital was being transferred from Britain to Jamaica—inverting the Williams thesis entirely! It was the increasing efficiency of the British economy during the Industrial Revolution that made the West Indies a profitable place to invest, and not the other way around.

So why did Britons submit to the planter monopoly? Coelho (like Ogilvie's explanation for guild persistence) blamed regulatory capture. Since the primary beneficiaries of the colonial system were the powerful plantation and mercantile interests, they had the lobbying power to keep Parliament on their side. Indeed, many planters ended up as MPs themselves, including the aforementioned Beckford and Pennant. It was thanks to the West India interest that Britain kept Canada, and not Guadaloupe, at the end of the Seven Years' War; the planters feared the consequences of increased (and highly efficient) competition in the imperial trading system.

Enter Solow

The plantation debate then went quiet, but in 1981, Joseph Inikori (get used to seeing his name) attacked the low-profit position hacked out by the new economic historians of the '70s. Inikori was annoyed with Thomas and Bean. Rather than an efficient market with free entry, he asserted, the slave trade was noncompetitive, dominated by fewer than a dozen top firms with much higher productivity than their peers. This small, closed group was able to exploit the inequities of market structure—inelastic supplies of trade goods and credit—to earn monopolistic profits of up to 50 percent, well in excess of Williams' exaggerated guess and several multiples of the 10 percent figure agreed on by Anstey and Richardson. Inikori discards the Davenport accounts, for which he only finds a maximum of 14 percent profits, on the grounds that Davenport had ignored non-British markets and used smaller ships than the bigger traders who appeared after 1780. Inikori also attacked Anstey for using an excessively low slave price and volume.

Anderson and Richardson (1983) returned serve with a comprehensive critique of Inikori's analysis. Inikori based his average profit calculations on a sample of just 24 voyages; thus a few key observations—five voyages fitted out by just one firm, Thomas Leyland & Co. between 1797 and 1805, that earned 71 percent returns—could skew the results. Moreover, successful firms were more likely to have preserved records, creating an upward bias. The remaining nineteen earned just 12 percent per venture, lower than in the Davenport sample. In focusing on venture rather than annual profits, moreover, Inikori ignored the substantial delays that investors faced in getting their money back. The most successful voyage in Inikori's sample, that of the Lottery in 1802, made a huge venture profit of 138 percent. But few of the proceeds were collected until 1811, nine years after the ship sailed! Anderson and Richardson argue that traders thought on the basis of annual return on capital, and that considering time factors profits were substantially lower. Moreover, Inikori's claims about concentration were pretty ephemeral—the largest eight firms in Liverpool controlled just 58 percent of investment, which is by no means exceptional. And as the table attached shows, there were a ton of little firms surviving alongside the large ones with high rates of turnover, indicating the possibility of entry.

Inikori (1983) responded that Anderson and Richardson failed to address his contention that the big firms did better in normal times and then made their fortunes in boom periods, but he himself avoided the essential point that traders rose and fell with the times, and that marginal firms were able to offer effective competition.

William Darity (1985) then entered and lambasted everyone. He argued that the "market structure" debate was pointless; bickering over the amount that excess actually exceeded "normal" profits gave no indication of how big those profits really were, and using primary sources to deduce profit levels was fraught by the "Darwinian" selection of successful traders' accounts. But Darity still thought profits were large. Reviewing the debate between Inikori and Anstey, he showed that the estimated rate of return was a function of slave prices, shipping tonnage (a proxy for outlay costs), the volume of slave imports, and the fraction of the voyage's value that returned to England as trading goods. Increasing the number of slaves imported to 1.9 million and the price to £45, estimated profits could be as high as 30.8 percent, very much in Williams territory.

Barbara Solow (1985) continued the revisionist turn with an attack on Engerman (1972). She does not contest his figures but rather argues that his maximally exaggerated estimate (all slave trade profits invested in industry) in which profits represent 39 percent of industrial and commercial investment is actually very large. For context, no single industry in the modern United States has made a contribution of equivalent scale. That's right, but it's totally irrelevant because of the implausible assumptions involved in creating this upper bound. Sure, if trading profits were large, if all wealth was invested, and if all that investment went into industry, then there might be a case for Williams. But we know that the first is uncertain and the latter two are just flat-out wrong. So I don’t really see the point of this critique.

More convincingly, she adds that if Sheridan's West Indies profits are added to Engerman's total, then slave-related commerce could have contributed 5 percent of national income, or nearly 100% of gross investment. From this perspective, she suggests that the Williams thesis is irrefutable, if not provable. I guess. But that still doesn’t deal with the Engerman assumptions. There’s zero reason to suppose that planters were especially likely to invest all, or even most, of their savings in industry. Finally, she uses a simple model to show that reinvesting the capital sunk in slave enterprises into the British economy would have reduced domestic profits, investment, and thus national income. This exercise is entirely speculative and I’m not sure why you should believe that the effect was of a substantial magnitude.

David Richardson (1987a) ripped the scab off the wound of the profits debate with a further analysis of the market structure and internal workings of the slave trade. He argued that slaves were expensive to transport and subject to high and highly variably levels of mortality during the Middle Passage, which, combined with the competitive market structure (sure to incite controversy) should have limited profits below 10 percent. Darity (1989) responded by basically repeating his 1985 points in a slightly more muted fashion (abandoning, for example, the inflated number of slaves transported from 1760-1800) and criticizing the low slave price assumed by Richardson. Richardson (1989) in turn replied that Darity had basically just copied Inikori and argued that the latter's high price estimates were derived from an overestimate of the share of slaves sold in foreign markets, where they fetched higher prices. He also noted the irony of Darity's claim that the profits debate was a "diversion" while still leaping into it once again.

Inikori, Darity, and Solow have one thing in common: though they can't resist bickering about profits, they all rightly disdain the debate as a red herring. In a remark that presages the later development of his broader theories, Inikori (1981), for example, writes:

[T]he emphasis on profits in the explanation of the role of the slave trade and slavery in the British industrial revolution is misplaced. The contribution of the slave trade and slavery to the expansion of world trade between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries constituted a more important role than that of profits. The interaction between the expansion of world trade and internal factors explains the British industrial revolution better than the availability of investible funds. This is the more so because it is now known that industries provided much of their investment funds themselves, by plowing back profits. In other words, capital investment during the years leading to the industrial revolution was related not so much to the rate of interest on loans (depending on the availability of investible funds) as to the growth of demand for manufactured goods, which provided both the opportunity for more industrial investment and the industrial profits to finance it.

Darity also focused on colonial commerce, arguing that "[i]t was not profitability or profits from the slave trade that were essential in Williams's theory, but that the American colonies could not have been developed without slavery" and labeling the profits debate a "numbers game" and a "diversion." Finally, Solow proposed that slavery "made more profits for investment, a larger national income for the Empire, and a pattern of trade which strengthened the comparative advantage of the home country in industrial commodities." Indeed, Engerman himself had pointed out the failings of his own neoclassical approach to determining the role of the slave trade, admitting that

It is rather clear that a basically static neo-classical model cannot provide a favorable outcome for arguments such as those of Eric Williams. That form of argument depends upon sectoral impacts resting on various imperfections in capital and other markets, and upon the characteristics of specific income recipients.

For whatever reason, then, the participants in the Williams debate accepted that the old arena of debate either was no longer or had never been productive. By 1985, Williams' own supporters had essentially abandoned the original thesis in favor of a new line of argument emphasizing trade and the Atlantic economy.

Toward the Atlantic Economy

The "Atlantic economy" focus of the 1980s generation wasn't a coincidence. The first volume of Immanuel Wallerstein's influential four-book The Modern World-System came out in 1974, and the second in 1980. Wallerstein argued that the emergence of a world economy in which a specialization between manufacturing countries in a "core" region and primary product exporters in a global "periphery" helped to spur industrialization in the former and an unequal pattern of development. He also linked the accretion of wealth in the periphery to capital accumulation in the core, in line with the Williams debates of the preceding decade. Indeed, Wallerstein cites Williams in volumes I and III. In one sense, what Wallerstein and other writers with dependista leanings, like Amin and Gunder Frank, did was to extend the Williams thesis to apply to the broader process of unequal exchange with regions outside the Western European core.

Wallerstein's books drew a heated response from Patrick O'Brien (1982) in the EHR. O'Brien, in one of economic history's most memorable lines, declared that "for the economic growth of the core, the periphery was peripheral." Most of Europe's trade was internal and most of its industries did not require large shipments of raw material. The periphery generated only sufficient funds to finance 15 percent of investment spending during the Industrial Revolution. O'Brien scoffed at the notion that "without imported sugar, coffee, tea, tobacco, and cotton, [Western Europe's] industrial output could have fallen by a large percentage." Leaving aside the empirically dubious claim that the IR could really have functioned without cotton supplies, O'Brien's figures don't really show that the periphery was very peripheral. On the contrary, O'Brien estimates that for 1784–86, profits from trade with the periphery amounted to £5.66 million, versus £10.30 million for Britain's total gross investment in the British economy—over 50%. Whether 7 percent is big or small may be debatable; 50 percent isn't. Nevertheless, Wallerstein appears to have backed down in his rather feeble 1983 comment on O'Brien's paper, in which he calls the claim that peripheral profits were essential to the IR a straw man.

A number of studies tried to explicate the role of mercantile capital in British, especially Scottish, industrialization. Devine (1976, 1977) showed that profits from the Atlantic trade were invested in shipbuilding, snuff mills, sugar refineries, glassworks, ironworks, textiles, coal mines, and other industries in London, the western ports, and their hinterlands. Bristol, for example, had twenty sugar refineries in its city center during the mid-eighteenth century and also housed copper and brass works. Liverpool developed similar facilities. Glasgow, home to the "tobacco lords," saw the rise of textiles, iron, sugar refining, glassworks, and leather manufactories. Yet it's not possible to show that the capital invested in these enterprises specifically came from the peripheral trade, as opposed to the other domestic ventures in which merchants engaged. Indeed, Devine (1975) actually calculated that only 17 percent of the investment in Scotland's cotton industry c. 1795 was financed by colonial traders; the proportion financed by colonial funds must have been even smaller. Further, Kindleberger (1975) argued that merchants engaged in reselling products made small profits.

Wallerstein's emphasis on the broader international pattern of trade, however, offered a way past the old "small ratios" debates. Research during the 1980s began increasingly to focus on trade and manufacturing development rather than investment funds, especially in light of the low levels of fixed capital actually needed in most British enterprises. Inikori (1987), for example, wrote that "To understand the broader relationships [between slavery and industrialization] the emphasis must be shifted from profits and the availability of investible funds to long-term fundamental changes in England: the development of the division of labor and the growth of the home market; institutional transformation affecting economic and social structures, national values, and the direction of state policy; and the emergence of development centers."

A special 1987 issue of the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, later published as a Solow-edited book (on the “legacy of Eric Williams”), heralded the change in direction. Solow, Inikori, and even Richardson, the main authors tackling the "industrialization" side, all accorded the Atlantic economy an important role in British economic development. Solow's article placed British slavery in the West Indies in the broader context of European conquest-driven plantation agriculture and discussed the formation, by 1700, of an "Atlantic system" (echoes of Wallerstein) based on slavery. Britain shipped manufactures to North and Latin America, Africa, and the West Indies. Africa exported slaves. The West Indies bought slaves and manufactures while exporting sugar. Even the free North American colonies were dependent indirectly on slave labor, since they sold their timber and fish to the West Indies planters, using the proceeds to buy British cottons and metal wares.

Solow argued that "slave-sugar complex" increased economic activity in the Atlantic basin, raising Britain's overall output thanks to the country's (assumed) endemic underemployment, and boosting the productivity of capital (investment) by introducing an elastic supply of labor. She also drew a straight line between industrial exports (60 percent of additional output over 1780-1800) and structural transformation. She appears to back off the claim that slavery "caused" the Industrial Revolution, but doesn't really, echoing Deane and Cole's argument that exports drove the eighteenth-century surge in manufacturing and that the American market took most of it. Solow's argument lacks, well, really any kind of provable claim or supporting statistical foundation—of course slavery was important, but by how much and against what counterfactual?—so it's hard to evaluate. But its general drift exemplifies the new, expanded interpretation of the Williams thesis as referring to the role of the entire Atlantic trading zone existing solely because of coerced African labor.

Richardson took a slightly different tack. Though his contemporary work on the "numbers game" attacked the Inikori-Darity-Solow position on high profits, he remained convinced that the slave-sugar complex contributed to British industrialization (which makes his vitriol toward the trio somewhat perplexing). His article points to the growth of British sugar imports, tied to rising incomes partly, changing tastes, and the availability of complementary goods (tea), in raising demand for British exports in the Caribbean. African and American markets took 10 percent of British exports in 1700 and 40 percent in 1800.

The most important single factor [in driving the British export boom], however, was rising Caribbean purchasing power stemming from mounting sugar sales to Britain. As receipts from these sales rose, West Indian purchases of labor, provisions, packing and building materials, and consumer goods generally increased substantially after 1748, reinforcing and stimulating in the process trading connections be-tween various sectors of the nascent Atlantic economy. Data on changes in West Indian incomes and expenditure at this time are unfortunately lacking, but … gross receipts from British West Indian sugar exports to Britain rose from just under £1.5 million annually between 1746 and 1750 to nearly £3.25 annually between 1771 and 1775 or by about 117 percent.

Rising West Indian proceeds from sugar sales had a direct impact on exports from Britain to the Caribbean and, as planters expanded their purchases of slaves from British slave traders, on exports from Britain to Africa also. Customs records reveal that the official value of average annual exports from Britain to the West Indies rose from £732,000 between 1746 and 1750 to £1,353,000 between 1771 and 1775, and that exports to Africa rose over the same period from £180,000 to £775,000 per annum.

Like Solow, Richardson also argues that North America's balance-of-payments surplus with the Caribbean was necessary to offset its trade deficit with Britain. Summing up, he finds that the West Indies added nearly £1.75 million to British exports from the late 1740s to the early 1770s, accounting for nearly 35 percent of the growth in British overseas sales. But there's a twist. After accounting for re-exports, Richardson finds that the Caribbean exports (of which 95 percent were manufactured) accounted for just 12 percent of the growth (Deane & Cole numbers) in British industrial output from 1748 to 1776. That's not nothing, but it's hardly the stuff of revolutions, either. And it assumes that resources used in producing Caribbean exports could not have been reemployed, exaggerating the colonial contribution.

But Joseph Inikori's article—"Slavery and the Development of Industrial Capitalism in England"—is by far the most sweeping. Borrowing from development/trade economics and Marxist theory, Inikori adumbrates his own theory of Britain's rise. Medieval England was a classic undeveloped economy, lacking adequate markets for land, labor, and capital, with little division of labor and bad institutions. Two autonomous forces operate to produce economic and institutional change: population and external commodity trade. Without the latter, the former tends to produce Malthusian crises. Trade, however, led to the development of private property, the format of a landless proletariat, institutional change, and the creation of a "sociological milieu" for scientific and technological discovery. In short, basically all factors in British development are endogenized to the growth of the export sector.

In medieval England, the raw wool trade led to the cultivation of marginal soils and the development of a land market, giving the country a more "capitalist" internal structure than France. This allowed the English to better exploit the opening of the Atlantic trade. As population growth threw Continental economies into crisis, Britain tapped woolen markets in southern Europe and for "other manufactures" in the Americas to create employment opportunities outside agriculture. Inikori argues that this foreign demand far exceeded that generated by income and population growth at home. Indeed, both of the latter two were consequences of trade (following Wrigley's early links between demography and income)!

And trade was a consequence of slavery. The New World's low population and large natural resource base combined with a high price of white labor raised slave prices in West Africa, leading to the extension of coerced labor. Slaves were the workforce of the American plantation economies, which in turn grew rapidly after the late seventeenth century and furnished the exogenous demand for British manufactures that drove institutional and structural change. Without slaves, the "Atlantic system" would have been smaller. Without the Atlantic system, the scaling up of textiles would have been impossible, especially given the weakness of European demand for manufactures amid Continental protectionism and proto-industrial development.

Inikori's theory was the most complete and sophisticated to date in 1987—indeed, it's more plausible than the one that Williams offered. The profits of the slave trade are incidental to Inikori's narrative, being the mechanism by which coerced labor was elastically supplied to New World plantations. Nevertheless, the "Britain-as-East Asian-developing country" story is incomplete. Why, for example, did Britain export sheep in the Middle Ages, and why was the English state so enthusiastic about and successful in doing so? Why didn't these agricultural commodity exports prove a resource curse?

Inikori also doesn't really explain the links between textile production and technological change, and his assumption that discovery depends on "social context" is totally half-baked. The same goes for institutions. It's actually sort of a Smithian doux commerce take on North: institutions and markets solve all problems, so we just need to explain why they arise—and we can do it with the Atlantic trade! His explanation of why Britain's colonies mattered, but those of her mercantile rivals didn't, isn't an explanation at all—idiosyncrasies of colonies lead to idiosyncratic national outcomes? Really? And treating export demand as an exogenous factor discounts the role of internal factors (plantations only exist because Englishmen want sugar), culture, and political economy in creating export markets. Inikori also doesn't rigorously explore backward linkages from wool to cotton (I guess textiles are textiles!), obscures specifics of production technology, and ignores coal, iron, and steam.

Nevertheless, the fact that Solow and Engerman (who’d smote the Williams thesis fifteen years before) had come together to edit the volume indicates a rough consensus about the big thematic shift in how historians thought about the economics of the slave trade. For the most part, they abandoned a very wrong position and moved on to one that, despite less direct empirical evidence, is more in line with our intuitions about how economic growth happens. We’ll tackle that in Part II.

Very good and useful! Some thoughts:

1. Someone should do a Fogel-No-Railroads study on No-Cotton. What if a disease had killed all the cotton in the world in 1500? People wouldn't have gone naked. They would have used flax and wool, the more expensive threads. How much would GDP have fallen? Would growth have been affected at all?

2. Similarly, how about No-Settlement? What if the Spanish had taken the entire New World and not allowed settlement north of Mexico? How much European GDP would be lost?

3. Similarly, No-Black-Slaves.

4. As many in the survey noted, the first-order effect of having a big slave economy in the New World is to hurt industrialization in Britain, not promote it. The Spanish having a lot of wealth in the New World from minerals didn't lead to Spanish industrialization; more the opposite. If Jamaica plantations ahve amazing profit rates, that means all the British capital would flow to Jamaica, not Yorkshire.

5. GOIng the other way, but small: When a Jamaican planter made his pile, he used it to buy an estate in England, to be sure. But that's just a transfer, to the extent it's land rather tahn mansions. The old squire, enriched by the Jamaican purchase money, would invest it, whether in cotton mills or back to Jamaica for slaves and expansion of the sugar plantations.

Gosh, much to ponder, much to consider. Thank you for this interesting take on a much misunderstood period.