Keeping Up with Economic History

A Guide to Productivity and Efficiency... in your Academic Reading.

Staying current in anything—sports, news, literature, etc.—is hard. But for the economic historian, academic or amateur, following recent research and understanding the state of the art is literally part of the job—and much of the fun. In this week’s newsletter, I’m offering a few suggestions for keeping up with our ever-changing discipline.

One of the primary benefits of diving into any field is watching the work progress (or digress) and discussing the newest findings with friends and peers. With the constant flow of information available in and around the academic literature, however, it’s difficult to know where the research and researchers stand. The key debates in economic history—the Great Divergence, the slavery question, the pace of the Industrial Revolution—are easy to see in hindsight, but with talks, papers, and articles going public on a daily basis, sorting the important from the irrelevant seems an overwhelming task. How are we to extract a useful signal from all this noise?

Here are a few of my suggestions, focused on the three main channels through which I consume information related to research in economic history. Two basic principles underlie the whole structure: focus intensively and filter aggressively. The former ensures that you hear only from those you care about; the latter that you hear only what you care about. Feel free to sample the ideas that seem appealing and modify them at will; your interests will at best overlap only partially with my own.

Twitter

Twitter can be a distraction and a time-suck, but there’s great content out there if you know where to look. On any given day, the #EconTwitter and #econhist communities are drawing attention to papers, announcing seminars, and chatting about the latest findings in their respective fields. In the ideal, it’s a mixture of discussion forum and message board without geographical constraints. The question is how to see only that content.

Answer: Twitter lists. Though Twitter doesn’t promote this feature, I’ve found it essential to using the platform. Building and maintaining a list is painstaking and takes time, but fortunately, I’ve done the hard work for you. For the last year, I have meticulously curated an economic history list, consisting of 128 academics from around the world (and a few journalists, too) that I take to be representative of the active research community. Whether it’s Adam Tooze’s chart barrage or another Pseudoerasmus mega-thread, interesting data and papers are perpetually floated; . theories propounded and pilloried; and recondite tomes screenshotted. Scholars requesting data, extending conference invitations, and offering research posts show up on a daily basis. This is more than just convenient; aggregating all these disparate voices creates a semblance of a conversation, giving the reader and participant a sense of what’s going on in economic history at the time.

You can follow the list HERE. If you know anyone who should be on this list who isn’t already, please let me know.

Feedly

Economics is blessed with a litany of talented academic bloggers, but keeping track of updates to their disparate websites is inconvenient. Remembering to check EconLib, MR, and Conservable economist is not worth the mental effort, and subscribing to all of them is a path to an unusably cluttered inbox.

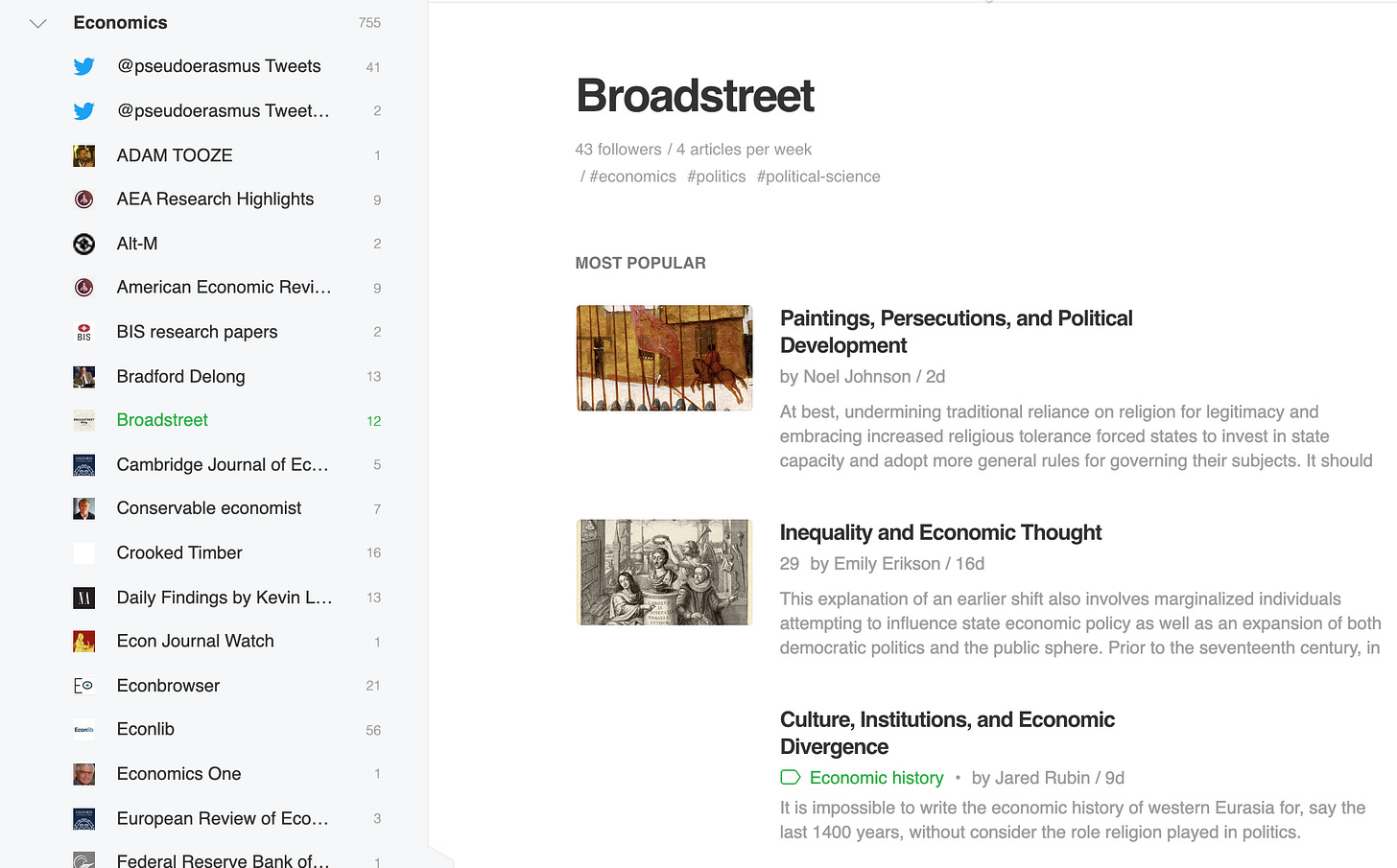

Luckily, RSS feed readers offer a streamlined solution. I use Feedly, available in both paid and free versions. Simply enter the links of the blogs and newsletters that you want to follow, and the latest updates will appear—usually in readable form—in your aggregated feed. You can sort these into category-based folders, which Feedly in turn orders by recency and popularity. Moreover, the paid version uses natural language processing to pick out topics of interest (“economic history,” say), creating a purely subject-focused subfeed from articles culled from all of your blogs.

I use Feedly to follow most of the usual economics blogs, as well as dozen or so journals—the Economic History Review, the Journal of Economic History, and the European Review of Economic History, among others. A relatively new feature is the ability to follow Twitter users, so I’ve added Pseudoerasmus to the list. I’ve found that most productive economic history feeds are Broadstreet, the Long Run (accessible introductions to EHR articles), and Bradley Hansen’s blog.

Email

Most of us have oversubscribed to newsletters—no thanks to Substack!—and other email services, with the result that we read only small percentages of the contents of our inboxes. Or maybe I’m the only one intimidated into apathy by a thousand unread messages. In any event, I have a few propositions for making email usable again. First, take the obvious step and reduce your direct email subscriptions to a few critical publications—those that you read thoroughly and no others. In economic history, those might be Anton Howes’s Age of Invention, the EH.net mailing lists, and Vincent Geloso’s blog. You can relocate the rest to Feedly, which does—see above—the hard work of content curation for you.

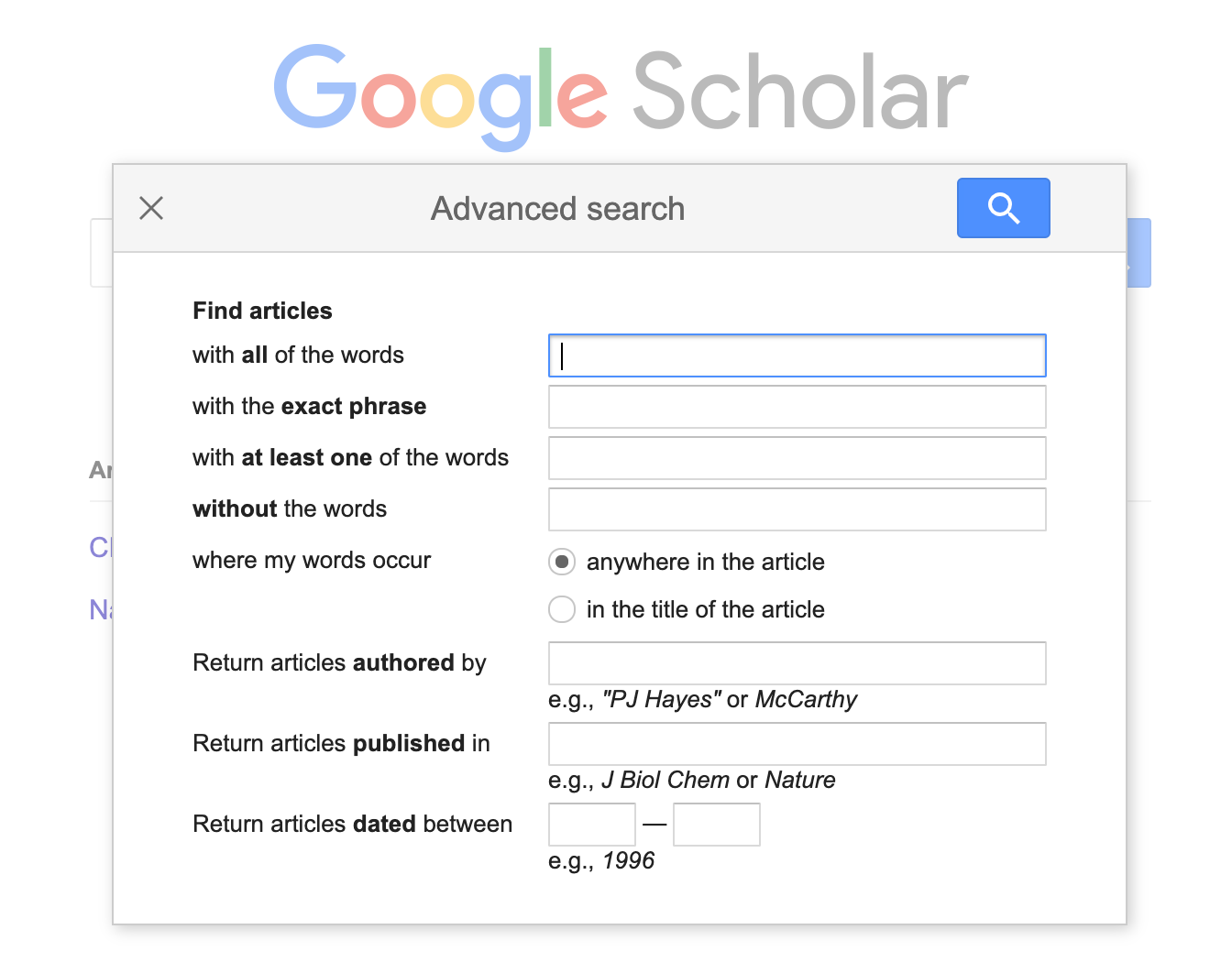

The real secret to email-based reading, however, is Google Scholar alerts. Many of you likely already have some general keyword searches, but few know that you can be far more efficient. By using the “Advanced Search” feature, you can get notifications for new publications citing specific papers—so whenever research is published with a bearing on a canonical work in the discipline, links will show up in your inbox. The choices of topic will be idiosyncratic to the individual, but I’ve found that alerts for Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence and Robert Allen’s “The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War” frequently produce results worth reading.

As I noted above, these tips can be modified and selected from piecemeal, and how you use them will depend on your interests and reading preferences. Nevertheless, I think that using them in some fashion can help to make the colossal, painstaking task of sifting through recent research and publications a little easier and more enjoyable.