The Endogenous Revolution and the Industrial Revolution

Bob Allen, E. A. Wrigley, and the Feedback Loops that Transformed Britain

Following last week’s post on urban pull, I discuss the process of “simultaneous causation” supposed by Robert Allen and E. A. Wrigley to have created positive feedback loops between city growth and agricultural productivity. I also speculate on the causes of Britain’s escape from the negative feedback that characterized even the most advanced European economies during the period.

Most historical explanations are unidirectional. The Global South de-industrialized because new textile technologies allowed British producers to undercut domestic hand-producers with low prices. Steam engines lowered freight rates by dropping shipping times, integrating global markets for foodstuffs. One of high wages, foreign trade, or British ingenuity—or some combination thereof—started the Industrial Revolution. One-way causation doesn’t imply a lack of complexity or nuance, but rather a particular perspective on the relationship between causes and consequences: assuming independent and dependent variables that interact in ways easily amenable to statistical testing. Endogeneity is something to be avoided or compensated for when building hypotheses, especially qualitative ones, not built in. Yet truly independent variables and outcomes without backward causation are rare in realistic explanations. History is endogenous. Two of the most compelling explanations of early modern British development—those of Robert Allen and E. A. Wrigley—embrace that fact, and better understanding the mechanics of their theories is essential to coming to grips with the precocity of Albion.

Last week, we discussed some ideas promulgated by Pseudoerasmus and Anton Howes on the interaction between Britain’s high-wage urban economy and the pre-1700 agricultural revolution—namely, that urban demand for food and labor was the main driver of agrarian change. Yet an “industry leads agriculture” view, while provocative, is an oversimplification of the proposed dynamics. The Pseudo-Howes position (or “monolith,” as Joe Francis terms it) is based on a research program honed by Allen and Wrigley over more than three decades. Both scholars present slightly different interpretations of the city-country relationship, and broadly see something less than eye-to-eye on the overall course of British development. Yet one obvious thread unites the two: the feedback mechanism. Allen and Wrigley agree that agriculture and industry were involved in a process of simultaneous causation—that urban manufactures stimulated the expansion of farm output and productivity, which in turn allowed a greater share of the population to migrate to cities. This positive feedback loop was almost unique in Western Europe and led to a near-unprecedented degree of urbanization and structural transformation. Only the Netherlands, a country with analogous characteristics, could boast the same extent and qualities of urban development by the late eighteenth century, but this apparent parity would not last. Wrigley states his version of the theory most succinctly his 2016 book The Path to Sustained Growth:

Agricultural productivity set limits to the urban growth that could take place, but agricultural productivity was itself strongly influenced by urban demand. In the absence of a substantial urban sector, in rural areas there was little incentive to produce an output greater than that needed to meet local needs. In other words, agricultural productivity and urban growth might be characterised by either negative or positive feedback. If the urban sector was trivially small and stagnant there would be minimal incentive for increased agricultural output since any surplus over local rural needs would be unable to find a market. If, however, the urban sector was significant and growing it created an incentive to increase agricultural output, thus ensuring that demand and supply remained in balance as urban growth progressed (Wrigley 2016, p. 45).

Cities needed rural areas to provide food, fuel, and raw materials. In England, these products were primarily grain, firewood, and wool. The efficiency with which English farmers could supply them to the cities was the rate-limiting factor on the pace of urbanization. In 1600, the 200 thousand inhabitants of London consumed the produce of 640,000 acres, assuming that 3.2 acres of grain (and no meats, cheeses, or fruits) were needed to feed one person. A similar calculus applied to 1800, when London’s population had swelled to nearly one million, yields a figure of 3.1 million acres—and for England’s entire urban contingent, 7.6 million acres, or two-thirds of the arable acreage of the country. Demand for non-cereal foods and fodder for transport horses would have increased this “footprint” even more. Since all this had to come from the agricultural surplus, the possibilities of maintaining such a population—let alone as a large share of the total—would have been strictly limited. And we haven’t even accounted for the 11.46 million acres (31 percent of the Anglo-Welsh land area) required to meet urban firewood needs. Fortunately, grain yields improved significantly from 1600 to 1800, doubling from 12 to 24 bushels per acre. This reduced the food catchment area of Britain’s cities to just 2.7 million acres—so land area used increased by a factor of 2.5 against a seven-fold surge in the urban population. Since the rural workforce remained static, urbanization leapt ahead while farm labor productivity doubled.

English agriculture was truly exceptional in Europe. Belgium, for example, started off with high yields per acre, but only raised them by increasing labor inputs and diminishing productivity. Since the surplus per worker determined the size of the non-rural population, Wrigley attributes the fall in the Flemish urbanization rate, from 23.9 to 18.9 percent, to this deterioration. Belgium was characteristic of most pre-modern economies. Falling marginal returns to farm labor with increasing population proved an equal drag on even the most productive European agricultural systems. Cities were small and stagnant, imparting minimal (and diminishing) incentives for expansion in the agrarian sector. Thus negative feedback was the Continental rule. But Britain was different. Cities like London served as powerful and growing sources of demand, pushing farmers to invest and improve. The security of urban markets allowed specialization to occur, especially between meat- and grain-producing regions, launching inter-regional trade in foodstuffs. City demand also provoked improvements in the country’s transportation infrastructure, which integrated markets and allowed farmers across the nation to respond to commercial incentives.

The existence of a large and rising demand for food, fodder, and organic raw materials associated with dynamic urban growth brought major changes in the scale and character of the demand for agricultural products and thereby induced matching changes in their supply. And once in train there was feedback between the two. The expectation that such demand would grow made increased investment in agriculture appear prudent rather than hazardous. As a result the growth of the urban sector was not constrained by increasingly tight supplies of food and industrial raw materials (Wrigley 2013, pp. 67-8).

Wrigley wasn’t certain why England, and not the Continent, was characterized by positive feedback. He noted that pontificating about resolutions to the country’s chicken-and-egg problem would be “idle,” given the deep and long-standing between demand, infrastructure, and productivity. The exceptional early modern expansion of London remained “imperfectly understood” and “puzzling,” though he did attribute the eighteenth-century rise of secondary towns to the “vigor of growth” in industrial cities and ports. Some of Britain’s agricultural advances might have been due to technical innovation and the adoption of crops (clover, sainfoin) and methods from advanced regions, such as the Netherlands and Flanders. In any event, Wrigley makes clear that much of this would have been for naught had England failed to exploit its reserves of coal, which loosed the land constraint for fuel (a more biting issue than grain by the eighteenth century). The coal trade—especially the Tyne-London shipping route—also relied on urban demand for development, but this exogenous relief mechanism ended up being just as important as positive feedback. For Wrigley, the absence of fossil fuels meant that collision with a hard Malthusian ceiling was inevitable for advanced organic economies.

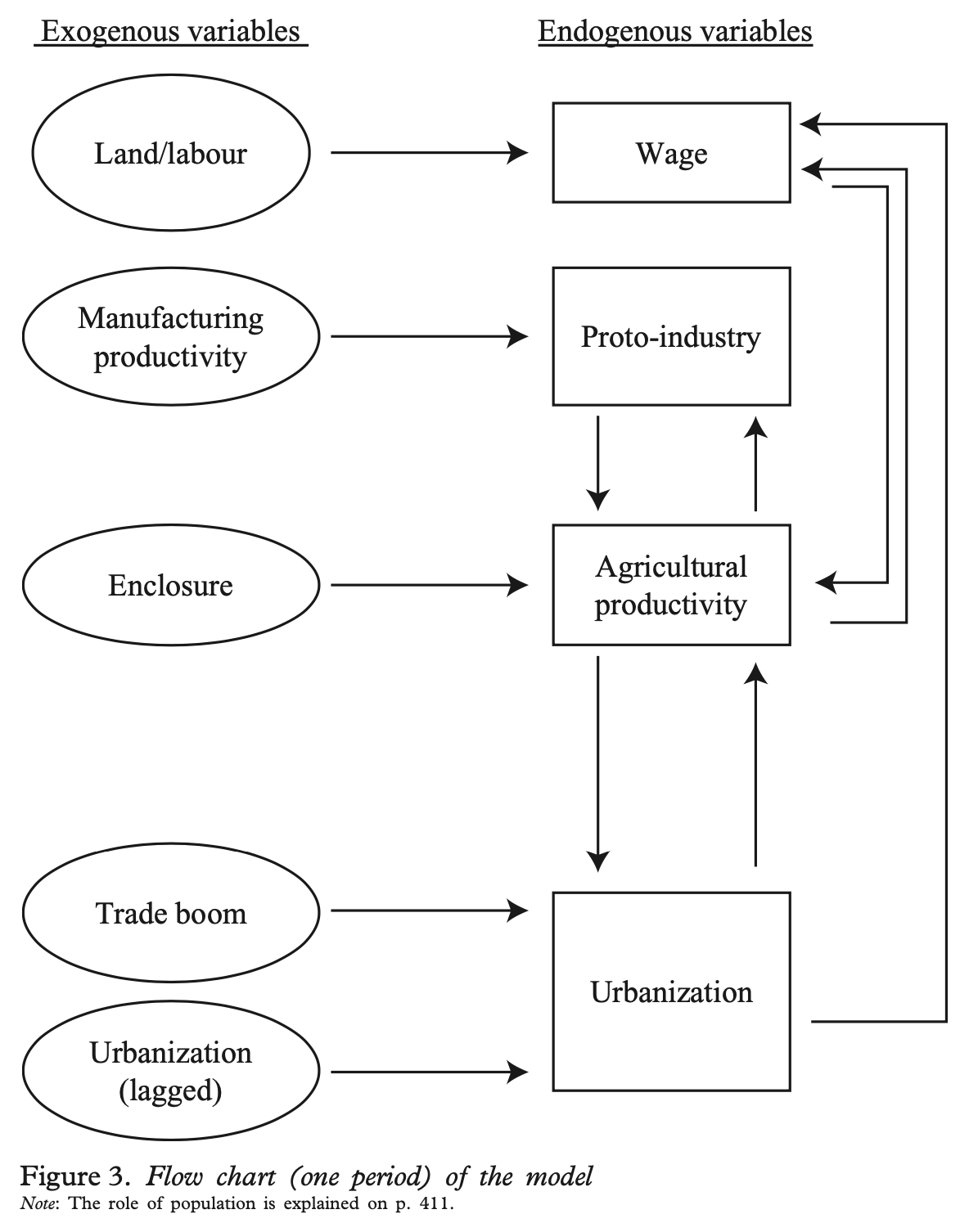

Allen took a quantitative tack toward unraveling the urban-rural feedback loop. In his 2003 paper “Progress and Poverty in Early Modern Europe,” he developed a five-equation model simulating the paths of population, wages, urbanization, agricultural productivity, and proto-industry in a series of pre-industrial economies. If you’ve read his more famous work, The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, you’ll probably be familiar with the flowchart—borrowed from the paper—describing the interactions between sets of exogenous (trade, the land/labor ratio, manufacturing productivity, and enclosure) and endogenous (the above listed) variables. Trade and farm surpluses boost city size, which in turn increases rural productivity and wages. Wages increase agricultural product, which in turn influences the growth of proto-industry and also rebounds back upon real incomes. In short, the model is a “recursive system,” in which four equations solve for the endogenous variables in terms of each other and the exogenous variables. “[T]he view of development is one in which living standards, urbanization, proto-industrialization, and agricultural revolutions were mutually reinforcing,” writes Allen. “None was a prime mover pushing all of the others forward.” His model tests the quantitative significance of each of the proposed “outside influences” on the feedback mechanism, as well as the strength of the links between the outcomes.

For our purposes, the crucial equations are those assessing the role of the various exogenous and endogenous factors in determining urbanization and agricultural productivity. In the former case, farm efficiency and trade volumes—as well as persistence—were the principal factors determining city size. Agricultural productivity, however, was primarily driven by the urban and proto-industrial shares of the population as well as the real wage rate. Agrarian institutions, especially enclosure, made next to no difference. Urban demand, operating both through the size of the non-rural population and through high wages, put pressure on agriculture to increase output through investment, technological adoption, intensive cultivation, and specialization. The successful growth of productivity in turn enabled cities and industry to expand even further, raising wages and restarting the cycle once again. Allen’s England was transformed by an upward spiral of rural and urban expansion, both of which were powerful incentives for change in the other. Even without the advent of the coal-based energy economy, the stirrings of exponential growth were apparent.

But Wrigley’s puzzle remained apparent: why did this positive feedback loop exist in England, but not on the Continent? What allowed the Isles to transcend the near-universal braking mechanism of diminishing returns to labor, transforming population growth from a curse into a boon? Unlike Wrigley, Allen felt that the origins of the feedback process could be identified. At the end of the paper, he simulated the trajectory of the English economy in a variety of counterfactual scenarios to determine the importance of a bank of exogenous factors in producing the country’s differential growth path. He found that enclosure had next to no effect on real wages, agricultural TFP, and urbanization, ruling out the exogenous transformation of agrarian institutions as a motive force in British development (as Marx, Brenner, and a swathe of English economic historians had supposed). In the absence of the “landlords’ revolution,” Britain would have grown at an identical rate to that which actually occurred. What actually explained Britain’s structural divergence from the continent up to 1800 were the twin forces of trade and manufacturing productivity. In the absence of these two factors, urbanization, agricultural TFP, and real wages would have collapsed back to continental levels and either stagnated or declined after 1500. Commerce and industry fully explained Britain’s exceptional city growth by comparison with the continental norm. “In the absence of the growth-promoting factors,” Allen argues, “the history of England would have resembled that of France, Germany, or Austria.”

The seventeenth century saw a shifting in the balance of wool manufacturing from Southern to Northwestern Europe, as the English and Dutch began to produce the “new draperies,” light worsted patterned on Italian styles. The imitations actually drove out the original Italian varieties—despite equivalent wage and input costs—thanks to a surge in productivity, which doubled between 1550 and 1620 (while that for traditional broadcloths remained static). By 1700, 40 percent of the country’s woolen output was exported, and this quantity represented 69 percent of all manufactured exports. Three-quarters of London’s exports and re-exports were of cloth in the 1660s, most of which went to the Mediterranean. We need not posit that these industries comprised an especially large share of the country’s—or even London’s—total product to see their vital differentiating role. Trade not only employed “20,000 dockworkers,” but also required a complex array of ancillary professions and services: domestic transport providers, insurers, shipbuilders, coopers, rope-makers, and many others. And these people in turn needed to be fed, clothed, housed, and heated. Small additional stimuli could account for larger additional regional concentrations beyond direct contributions to employment and GDP. Induced improvements to transport infrastructure (roads and canals) increased the locational advantages for other industries moving to urban areas. And this all neglects the urbanization directly produced by trade in the form of new cities; in East Anglia and Norwich (which doubled in size from 1600 to 1700), new industrial concentrations arose, attracting foreign and domestic artisanal talent. Port towns like Bristol and Great Yarmouth doubled in size during the seventeenth century, while Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool (quadrupled in size from 1700 to 1750) arose from nothing to become three of the country’s largest cities by 1750. A brief glance at the list of England’s most populous urban centers in that latter year leaves one under no illusions as to the causes of town development.

We can thus spell out the dynamics of the feedback loop for Britain. International trade, imperialism, and the development of the exportable “new draperies” created a large, high-wage urban economy. Faced with the “challenge” of feeding this swelling non-rural population, farmers increased output—stimulated by rising prices—and economized on labor (through pastures and engrossment). Manufacturing productivity also pushed farmers to deliver more raw materials, fuel, and labor to the burgeoning centers of rural industry. “[T]he hallmarks of the English agricultural revolution… should be seen as responses to an urbanized, high wage economy rather than as autonomous causes.” Higher agricultural productivity in turn released the constraints preventing larger shares of the population from migrating to cities, raising wages and restarting the feedback loop as a greater surplus was required for its maintenance. With each cycle, commercialization, infrastructural development, and capital accumulation all increased. So did industrial and proto-industrial agglomerations, especially in textiles, which may have provided—after a series of tinkering-based innovations—the launching-pad for British take-off. The exogenous motion imparted by trade and manufacturing to each loop kept the cycle spinning forward rather than backward, as was the Continental norm.

Industrial and commercial success drove the transition from negative to positive feedback. What remains to be explained, then, is not the direction of change in early modern Britain, but rather the sources of England’s early modern dominance in manufacturing and trade. Even before the Industrial Revolution, she had supplanted the Dutch Republic—the previous leader—in both categories, capturing the entrepot trade, European export markets, and Amsterdam’s role as Europe’s commercial and financial capital. As England waxed, the Netherlands waned, with agricultural productivity and GDP per capita stagnating—further evidence that organic economies needed an outside stimulus to urban demand to keep the feedback mechanism positive. We must also discover the extent to which English commercial and proto-industrial development determined the advent of the Industrial Revolution, and the potential mechanism by which this happened. Was England’s destiny merely “advanced organic economy” status without the further intercession of coal? Or was positive feedback sustainable, perhaps even potentially exponential? Allen’s approach is geared toward the empirically-contested high-wage explanation, so we need to look for other potential links between urbanization and industrialization. We can entertain hypotheses regarding increasing returns to scale from industrial concentration, innovation stimulated by market size, and a host of other possibilities. But this remains the hazy frontier of our knowledge of the British Industrial Revolution.

Great article David! Maybe I have to read this many times 😅

This was a truly encouraging read. Too often, economic history is framed in overly simplistic, linear terms—where factor X (be it technology, capital accumulation, or Enlightenment ideals) leads neatly to outcome Y, typically the Industrial Revolution or the rise of Europe. But as your essay powerfully illustrates, the reality is far more complex. The emergence of modern economies was driven by intricate interactions and reinforcing feedback loops among many factors.

As someone who has long believed in this dynamic, nonlinear perspective, I’ve hesitated to articulate it publicly—especially on Substack. I did explore a related idea back on Medium, focusing on how expanding market size could create a feedback loop of growth (https://medium.com/@exchangism/history-de12d6a41fc4 – long post, but the key points are at the end). Your post has given me the push I needed to write more openly about this on Substack as well. Thanks for the inspiration.