Week of December 27, 2020

Monetarism, Free Trade, and the History of Economic Thought

This week, I’ve pillaged the JEP once again for two papers in the history of economic thought and another meta-paper attempting to justify that discipline as a relevant part of economic science. Though I am skeptical of the arguments made for the latter point, the fact that two prominent economists (not historians) wrote the former papers hints that some do take intellectual history seriously as a method of understanding contemporary ideas. I also look ahead to the potential stance of Janet Yellen at the Treasury in the context of her tenure as chair of the Federal Reserve and overview a simulation of an early trade shock in nineteenth-century England.

Merry (belated) Christmas, and enjoy the reading.

Links

George Selgin | CMFA Working Papers | December 3, 2020

Leafing through the minutes of Federal Reserve meetings and speeches from the last decade, Selgin examines the motives behind Janet Yellen’s 2015 interest rate hike ahead of her assumption of power at the Treasury. He argues that, far from becoming hawkish or properly responding to improving economic conditions, Yellen was pushing through a pre-arranged return to perceived “normal” rates. This was based not on unemployment or inflation data, or even a flawed application of the Phillips Curve trade-off between the two, but on a semi-aesthetic view of where rates had stood during the pre-crisis decade. The result was monetary tightening in the midst of a flagging recovery and the prolonging of the slump. Selgin alleges that the hikes, though moderate, were contrary to the Fed’s mandate, and that the “normalization trap” into which it backed itself represented a major policy error. The tone of inevitability assumed by the Presidents’ announcements casts doubt on the claims to technocracy made about the central bank. Remember what I wrote last week about a foolish consistency?

No History of Ideas, Please, We’re Economists

Mark Blaug | Journal of Economic Perspectives | Summer 2001

Two decades ago, the history of economic thought (HET) had long been an antiquarian science, rejected by orthodox economists since Pigou as a catalogue of “the wrong opinions of dead men.” Blaug, the author of the now-standard textbook Economic Theory in Retrospect, sets out to prove the utility of his subdiscipline and lay out the reasons for its decline in American universities. The latter appears to be relatively obvious; modern economists are mathematicians, not philosophers, and have limited time (and interest) to expend on side projects in history that might otherwise be allocated to quantitative training and publication. As for the use of HET, Blaug argues—unconvincingly—that studying economic ideas in their original contexts is necessary (or at least more marginally productive than math) for complete understanding. He differentiates between rational reconstructions, in which classic theories are rewritten as contemporary economic models, and historical reconstructions (Schumpeter’s “geistesgeschichte”), which interpret works in a manner presumably agreeable to the original authors, and states his preference for the latter on the grounds that rationalism teaches one more about mathematical modeling than the ideas under study. He labels the conclusion of Kenneth Arrow and Frank Hahn that Adam Smith discovered the possibility of Pareto-optimal equilibria under perfect competition a “historical travesty,” for example, and shows Robert Lucas’s evaluation of Hume’s quantity theory of money to be based on an anachronistic misreading. His “ultimate justification” follows: every idea is “the end-product of a slice of history” and cannot be fully comprehended without an understanding of its “intellectual development.” He draws an analogy here between learning calculus through the Newton-Leibniz debates and assimilating Keynesianism through the confusions of Hayek and Robbins in the face of the Depression. As attractive as this notion may seem, however, there appears to be less applicability for modern economics, which has steadily become less theoretical and more quantitatively empirical over the last two decades. As long as economic ideas exist in rigorous and useful forms, the question “So What?” remains as devastating as ever for the intellectual historian.

J. Bradford DeLong | Journal of Economic Perspectives | Winter 2000

Looking back on a century of macroeconomic history, DeLong puzzles at the disappearance of a monetarist tradition whose chief precepts—the salience of frictions, the superiority of monetary policy, and the necessity of policy rules—were so central to the prevailing New Keynesian orthodoxy. He divides monetarist thought into four distinct schools: First, Old Chicago, Classic, and Political Monetarism. The former was comprised of the disciples of Irving Fisher, who crafted a mathematical quantity theory of money (as Hume had not) but could not explain—to Keynes’s disdain—business cycle fluctuations in employment and output. Old Chicago monetarism, allegedly a rational reconstruction of Milton Friedman, presented a sophisticated analysis of the limitations of monetary policy—the variability of the velocity of money and the multiplier in a world of fractional-reserve banks. Classic monetarism, pioneered by Friedman, sought to rectify these issues through banking reform (a 100 percent reserve system) and controlled money stock growth. The analytical stability program failed, but the residual anti-statism would prove influential during the neoliberal turn, reaching its apogee with the breakdown of the Phillips Curve and the Volcker Fed. Finally, Political Monetarism was a “stripped-down” Classic school whose simplistic assertions that velocity was actually stable and that money aggregates predicted demand proved empirically false, leading to the fall of monetarism as a distinct entity.

William J. Baumol | Journal of Economic Perspectives | Winter 1999

Thanks to the acerbic pen of John Maynard Keynes, modern economics attributes to the French classical economist Jean-Baptiste Say the dictum that “supply creates its own demand,” painting him as the founding father of trickle-down theory. Baumol convincingly demolishes this myth. Say’s “Law of Markets” was more sophisticated and nuanced than recent authors believed. The central package of claims did include the assertion that the production of goods creates the income required to purchase them, but also accepted that partial overproduction might occur in the short term before being rectified by shifting profits under perfect competition. Say himself, in his correspondence with Malthus, wondered at the tendency for a “general overstock” of certain goods to arise, and even advocated that unemployment be ameliorated by public works programs. Baumol argues that Keynes’s flawed critique of Say as a proto-liquidationist in the mold of Schumpeter was the product of negligent reading and that later authors (like Oskar Lange) were similarly lax, comprehending only the first part of the Law. Furthermore, much of the Law—such as the notion that saving is immediately invested—had been derived from previous authors, specifically Adam Smith. Say, in sum, was neither as inflexible nor original as his contemporary caricatures propose.

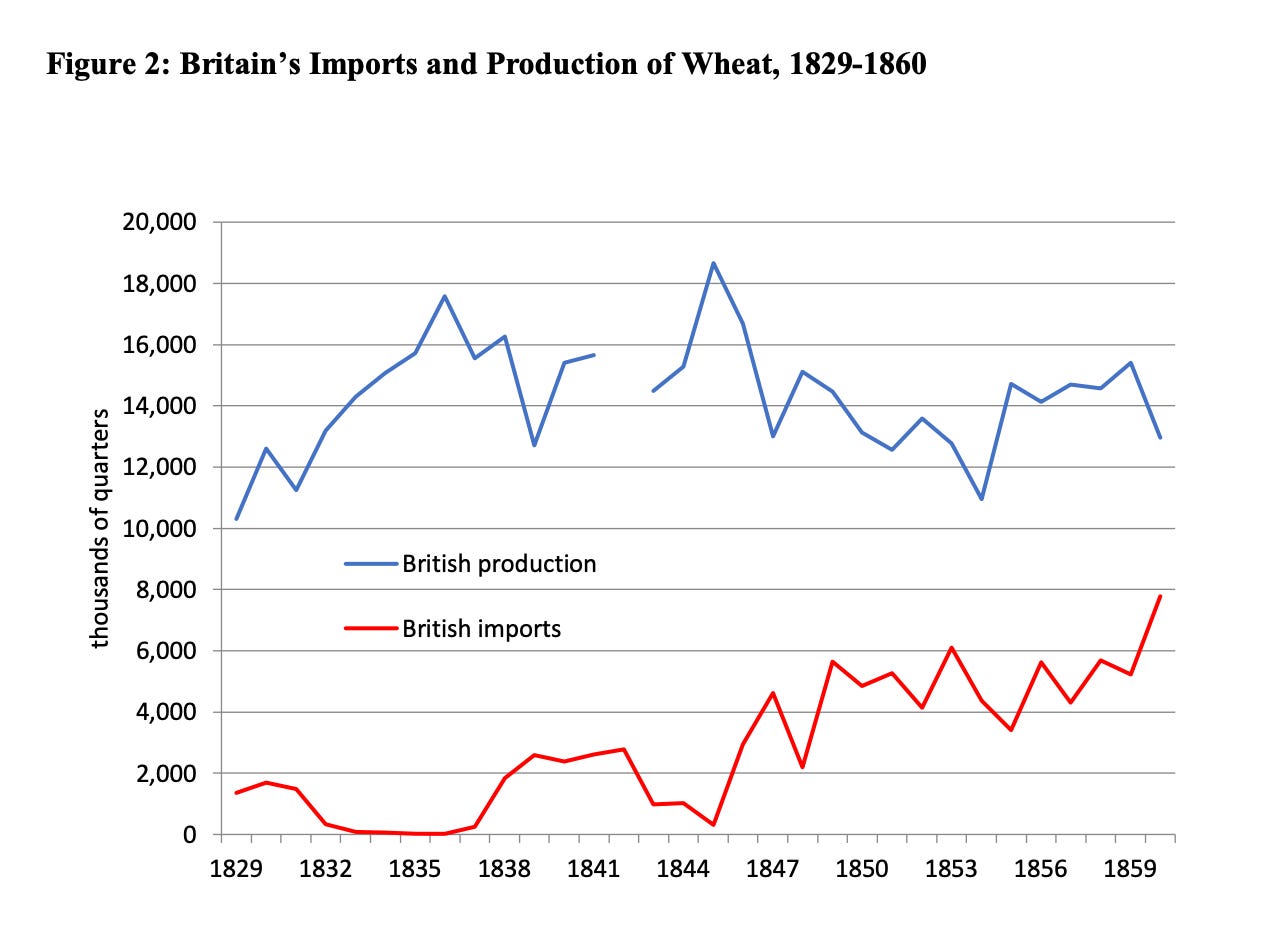

The Economic Consequences of Sir Robert Peel

Douglas A. Irwin and Maksym G. Chepeliev | NBER | November 2020

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, a cash-strapped British parliament passed the Corn Laws, a restrictive set of tariffs on imported grain. After decades of popular criticism, led by Malthus and Ricardo, Sir Robert Peel—then the Prime Minister—pushed through the abolition of the tax. The economic welfare results are reported in the above paper, which runs a simulation based on a general equilibrium model and input-output tables. While overall prosperity was static, reflecting the turning of trade terms against Britain (which raised import and lowered export prices), the top 10 percent of earners lost some income share to the bottom 90 percent. Landowners, undercut by imports (which rose by 67 percent), lost three percent and workers gained one percent, leading Irwin and Chepeliev to conclude that the tariff reduction was a redistributionary “pro-poor” policy. The fact that efficiency gains from open borders are outweighed by the adverse terms-of-trade effect is interesting, too, and reflects the class tensions frequently sparked by international commerce as interest groups experience differential outcomes.