Week of January 10, 2021

Wages, wages, and more wages. And a bit about trade.

In the latest edition of The Kedrosky Review, economic history elements have staged a complete takeover—for which I am wholly unapologetic. I review work on British and Indian wages, which appear to have diverged long before the era of colonization, as well as Greg Clark’s analysis of the effort-based character of American farm incomes. I also cover the role of tariffs in nineteenth-century Europe as well as that of trade in Indian industrialization, and discuss the first of (what will presumably be) many critiques of the cross-country regression literature.

Links

Poverty or Prosperity in Northern India? New Evidence on Real Wages, 1590s-1870s

Pim de Zwart and Jan Lucassen | The Long Run | June 3, 2020

Building off of archival British and Dutch sources, the authors construct a new database of real wages from towns in Northern India, covering a wide range of occupational classes—artisans, unskilled hands, and bookkeepers. Valuing wages relative to the price of a “subsistence basket” of goods reveals that the Great Divergence between Indian and European wages dates to the end of the seventeenth century, when incomes began a secular decline until the Bengal famine of 1769-1770. This evidence conflicts with hypotheses attributing economic prosperity to the pre-colonial Mughal empire and the collapse of Indian welfare to poor British administration. Indeed, wages were below levels required to purchase the daily subsistence basket for a family, indicating that Indian laborers were compelled to work for extended periods of the year before the Europeans arrived—and that they had to be assisted in breadwinning by women and children.

The Skeptic’s Guide to Institutions

Dietrich Vollrath | Growth Economics | November 18, 2014

I mentioned last week that I intended to discuss some critiques of the AJR “Colonial Origins” paper, and this series of four posts does that and more. Each of the first three reviews a “generation” of works in the institutional economics literature, an approach that Vollrath admits is “going to sound very antagonistic as I do this, which isn’t completely fair, but makes it more fun to write.” And more fun to read. His objection to the first generation of studies revolves around the fact that they fabricated “governance quality” indices as statistical centerpieces. These indicators (such as Polity IV) are at once “inherently arbitrary” and given “a strict numerical interpretation,” rendering the results all but meaningless (e.g. “Western-style social democracies are different from poor countries”). Moreover, they often reflect varying. outcomes rather than true institutional differences. The second generation, of which “Colonial Origins” was perhaps the flagship model, added instrumental variables to the cross-country regression style of the first. It inherited the arbitrary measure problem and also added the issues of instrument endogeneity (drivers of settler mortality likely affects GDP through other channels) and low data quality (36 of 64 observations have inferred data, which might come from a completely different ecoregion). The third generation (such as Dell’s 2010 “Mining Mita” paper) solved the ambiguity and endogeneity problems hampering the first two waves, but still failed to isolate the effects of institutions. “One possibility is that there was some other institutional structure left behind by the mita that limited development,” Vollrath writes. “But we have no evidence of any institutional difference between the mita areas and others. We simply know that the mita areas are poorer, and that could be evidence of a poverty trap rather than any specific institution.” His objections are well-founded and trenchant; considering that these studies are regarded as gold-standard works of economic history, the article is a concerning and necessary read.

The Bairoch hypothesis (or the “tariff-growth paradox” of the late 19th century)

pseudoerasmus | pseudoerasmus | December 25, 2016

The pseudonymous pseudoerasmus examines the evidence for the “tariff-growth paradox” suggested by economic historian Paul Bairoch, who argued that European countries that levied higher tariffs experienced faster growth during the pre-World War I globalization era. This informal finding was confirmed by an econometric study conducted by Kevin O’Rourke in 2000, supported by the work of Michael Clemens and Jeffrey Williamson, and contested by Douglas Irwin, who argued that the correlation was the result of settler economies using tariffs for revenue purposes. The former studies find that the relationship is strong for rich countries, weaker for the non-European periphery, and negative for the European periphery (e.g. Spain, Russia, the Balkans, etc.). Pseudo quotes Clemens and Williamson as suggesting that high-tariff countries exported to lower-tariff counterparts:

[E]very non-core region faced lower tariff rates in their main export markets than they themselves erected against competitors in their own markets. The explanation, of course, is that the main export markets were located in the Core, where tariffs were much lower.

Thus “Great Britain and others acted as free-trade sinks for exporting countries such as the United States (and Wilhelmine Germany) which protected their steel and other industries.” He draws a parallel between this scenario and the situation of the East Asian Tigers during the Cold War, when American markets served (for political reasons) as the importer of last resort in spite of the tariffs and subsidies wielded against US goods.

How (much) were British workers paid ? Evidence beyond wage rates

Judy Z. Stephenson | The Long Run | October 7, 2016

In this short blogpost, Stephenson summarizes the results of a 2016 conference on wage formation in the early industrial world held at the Institute for Historical Research. The participants generally found that day wages were both more complex and less broadly important than they had been treated in previous research. One study, conducted by Leigh Shaw-Taylor, proposed that cliometricians like Greg Clark and Robert Allen had failed to understand that the wages of the poor rather than average worker were predicted to shift under Malthusian theory. Jane Humphries and Ben Schneider presented evidence against Allen’s high-wage explanation, showing that only the most productive spinners in the country conformed to his expectations (derived from surveys by Arthur Young). Other studies reported variously that the incidence of casual labor rose during the 19th century, that unskilled Swedes earned below subsistence wages, and that miners were paid variable sums depending on season, efficiency, and work engaged. Stephenson herself presented a review arguing that few workers in 1800 (at least in London) were in fact paid in day wages, and that these figures are therefore not to treated as representative in the construction of macroeconomic aggregates. There’s more at the link, which is an excellent and concise survey of some of the empirical evidence informing debates on the origins of the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

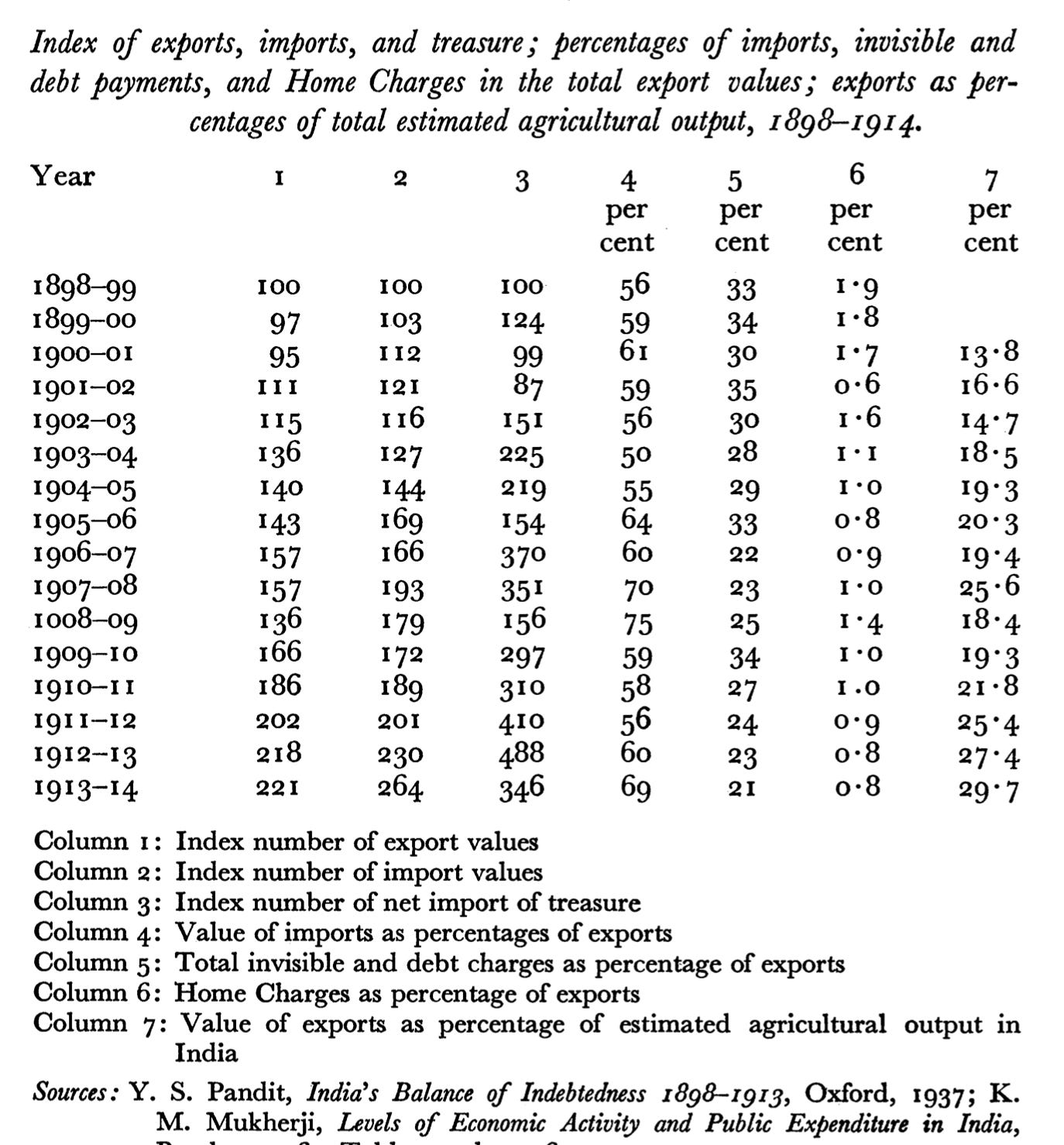

India's International Economy in the Nineteenth Century: An Historical Survey

K. N. Chaudhuri | Modern Asian Studies | 1968

Reviewing a series of central debates in Indian economic history, Chaudhuri contends that previous research has been dogged by methodological and theoretical errors, amounting to a “lack of understanding [of] the simplest terminology of international trade theory.” Nationalist historians such as R. C. Dutt, for example, showed a tendency to credulously accept popular interpretations of events and proceed in confirming them without questioning plausibility. The most controversial of these is the problem of international trade, which many uncritically assumed had contributed to Indian poverty through deindustrializing imports and the extraction of treasure. To the “crude view” that British competition destroyed Indian textiles, Chaudhuri replies that “[t]he general expansion in India's economy in the nineteenth century brought about by the construction of railways and the extension of agriculture, together with the rapid development of the cotton mills in the I870s and '80s, might actually have increased the size of the textile industry proportionately from what it had been in pre-British days,” adding that the true effect is at the very least unclear. He also attempts to refute the so-called “drain theory,” which postulated that there was an export surplus on India’s current that went unpaid as the result of interest, debt, imperial salaries, and freight charges. Dutt suggested that these fees absorbed as much. as a quarter of the national income. Chaudhuri, on the other hand, concludes that if “unilateral transfers” existed they were small and did not constitute a “net depressor” on the Indian economy.

Productivity Growth without Technical Change in European Agriculture before 1850

Gregory Clark | The Journal of Economic History | June 1987

Following the research agenda of “Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed?”, his more famous paper of the same year, Clark collects further evidence for the role of worker productivity and effort in determining wages. He shows that the differences between the pay of Anglo-American and Eastern European farm pay during the nineteenth century can be almost completely ascribed to more “intense labor” in the former regions. Clark demonstrates that a relationship exists between efficiency rates and wages across a variety of tasks (from threshing to reaping), and therefore that soil quality, land availability, and technology were minor factors in determining agricultural incomes.

The main source of high American and British outputs per worker was, it seems, high yields per acre compared with Eastern Europe. This appears to imply that the foundation of American and British farming prosperity was the use of advanced agricultural techniques, since there is no evidence that the soil quality in the northeastern United States or Britain was inherently any higher than that of the rest of Northern Europe. But while advanced techniques explains higher yields per acre, it cannot explain the higher output per worker in America and Britain, since in grain farming most of the labor inputs were proportional not to the area of land farmed but to the output.

The invariant bond between labor input and output suggests that most productivity differences, which governed the rewards, were the result of the speed with which Americans and Englishmen worked. “[E]ven where the same harvest technique was used,” Clark writes, “American and British workers were able to perform the work many times as quickly as in Eastern Europe or medieval England.” Once again, (as he specifically states in his conclusion), the character of labor determined the success of industries endowed with similar technologies and showed that exogenous variations in workforce quality (or at least attitudes) were important determinants of economic success.