Week of January 24, 2021

Divergence, Invention, and Inversion

This week, we explore a series of important topics in economic history, including several quite close to my heart. We begin with a critique of Pomeranz’s views of the Great Divergence showing early disparities in incomes and living standards across Eurasia. We’ll then discuss the theoretical underpinnings of invention under the high-wage explanation, the dynamics of long-run economic growth in England, and the social and economic basis for the English Civil War and Glorious Revolution. Each of these papers is exceedingly important in the economic history literature, and all of the authors are effectively canonized in the discipline.

Stephen Broadberry and Bishnupriya Gupta | Economic History Review | 2006

Following the publication of Kenneth Pomeranz’s groundbreaking The Great Divergence, the notion—presented forcefully in the book—that Eurasia in 1800 was “a world of surprising resemblances” gained traction in economic history and related fields. Pomeranz proposed that the lead regions of Asia, such as the Yangzi delta, were comparable with Europe’s most prosperous areas (the Netherlands and Britain) until the Industrial Revolution, when coal and colonies enabled the latter to escape from the pressures of rampant population growth. Broadberry and Gupta shatter the empirical basis for this theory. They show that while grain wages were close across Eurasia, silver wages diverged earlier, being significantly lower in Asia in 1500. This, the authors argue (via the Balassa-Samuelson framework), is evidence of low productivity in the tradable goods sector (manufactures). Europeans could purchase greater quantities of the latter with their higher silver wages and lower prices, while Asians necessarily had cheap crops because of their low wages. Broadberry and Gupta conclude—adding evidence on urbanization rates—that the leading East Asian regions actually resembled the lagging European periphery, where the same structure of low silver wages and high grain wages prevailed for similar reasons.

Robert C. Allen | Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization | February 1983

In a paper that appears in hindsight a theoretical framework for his later The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Allen argues that much innovation during the nineteenth century occurred through a process of “collective invention”—that is, through small increments in design inspired by the free exchange of technical information within industries. Important innovations arise not as the result of a single inventor, but a broad-based trial-and-error process occurring in new plant capacity with minimal direct R&D expenditure. As evidence, he cites the iron industry in Britain’s Cleveland district, showing that increases in blast furnace height and temperature during the second half of the century were part of an experimental process leading toward—and eventually overshooting—optimal levels.

[F]urnace height and blast temperature were increased in moderate steps The first furnaces built in Cleveland in the early 1850's were 45-50 feet tall. In 1858 Thomas Vaughan, and Hopkins, Gilkes and Co. and Jones, Dunning, and Co. blew in furnaces of 56-58 feet in height. This increase in size was prompted apparently by a desire to increase production but resulted in a noticeable fall in fuel consumption. As a result Bolckow-Vaughan rebuilt its short Witton Furnace to a height of 61 feet, which further reduced fuel consumption. Bolckow-Vaughan again led the way building in 1862 two 75 feet furnaces. These furnaces consumed even less fuel and their excellent records prompted Bell Brothers and Thomas Vaughan to build furnaces of 80 and 81 feet.

Collective invention was necessitated by the impossibility of patenting the innovations produced, which meant that researchers would receive low individual returns to any resources devoted to R&D, and consequently that the rate of change would be below the socially-desirable level. Since firms engaged in collective invention did not actually need to pay for research directly, however, advances could simply occur as a result of a high investment rate (which meant that new capacity with potential for experimentation was being installed). Allen goes on to show why firms would release valuable trade secrets, and further—presaging his later book—that collective invention leads to biased technological change augmenting expensive inputs (in Britain, labor).

The Political Foundations of Modern Economic Growth

Gregory C. Clark | Journal of Institutional History | Spring 1996

Clark contests the institutionalist interpretation of British economic take-off, associated—as discussed last week—with Douglass North and Barry Weingast, which posited that the constraints placed on Crown authority by Parliament as a result of the Glorious Revolution incentivized investment and growth. He collects data from yields on farmland, rent charges, and securities to contradict their primary source of evidence, the decline in interest rates on government debt after 1688, a trend that purportedly showed the increased security felt by investors under Parliamentary supremacy. Clark, however, demonstrates that interest rates had been declining in Britain since 1600, and that the period following the Glorious Revolution did constitute a break in trend. Moreover, rates did not respond in general to periods of political disturbance, suggesting that property rights were already secure. This serves as a confirmation of one of Clark’s broader theories of economic growth: that institutions are a necessary but insufficient condition for prosperity. The evidence is fairly comprehensive, but one should note that North and Weingast’s figures on government debt are not confuted—and even if rates did not decline, perhaps their stability despite massively increased state borrowing demonstrates new conditions.

The Condition of the Working-Class in England, 1209-2003

Gregory C. Clark | Journal of Political Economy | December 2005

This paper presents Clark’s original time-series for British working-class wages over much of the last millennium. He uses the data to prove a series of points about long-run economic development in England: that England followed Malthusian dynamics prior to 1600; that the Industrial Revolution was a protracted and gradual process, with the first productivity advances beginning as early as 1600; and that the “human capital explanation” (high skill premia leading to fewer children) is insufficient. For the first, he demonstrates—with the graph made famous by A Farewell to Alms—that population and wages varied inversely to 1600, after which point both began to increase secularly. In the second case, his series (depicted below) shows that the eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution was “preceded by a period of modest economic growth starting in the 1600s” and that resulting gains to workers were greater (having started from a lower base) than implied by previous measures. Finally, to defeat the human capital explanation of take-off, advanced by Gary Becker, Clark shows that the skill premium for craftsmen actually declined during the fertility transition, indicating that there was no economically-incentivized shift to producing fewer children of higher quality. Instead, the change indicates an alteration in preferences. The paper is short and readable, serving as a necessary introduction to British macroeconomic history over the longue duree. If you read any of the linked papers, this should be the one.

The Rise of the Gentry, 1550-1640

R. H. Tawney | Economic History Review | 1941

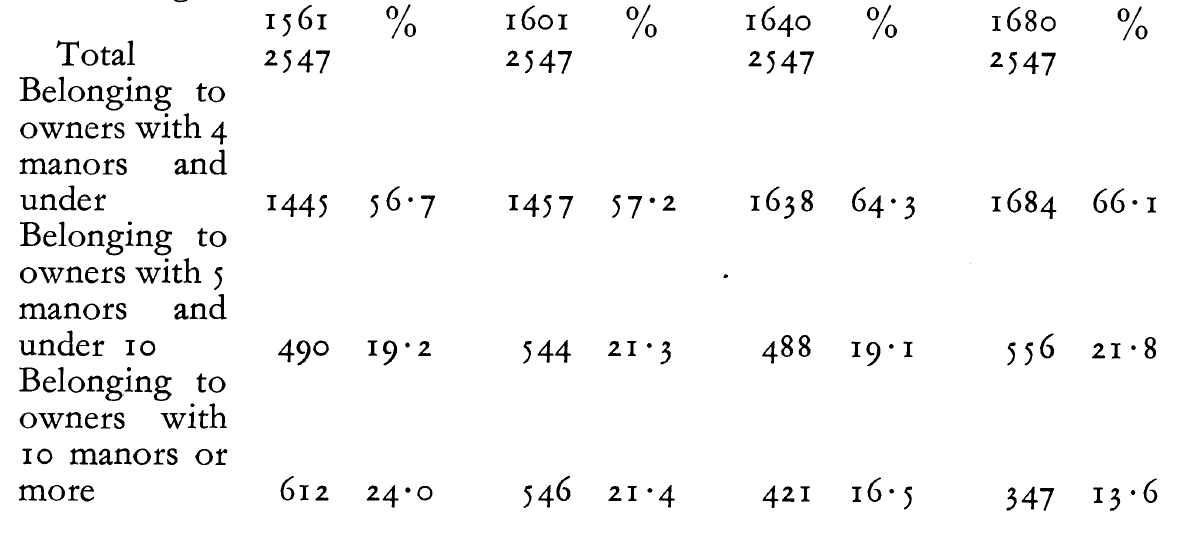

In this classic demographic study, the early economic historian R. H. Tawney eloquently describes the dramatic social changes occurring in England prior to the Civil War. He theorizes that between 1550 and 1640, power—measured by wealth and. the balance of landholding—shifted from the traditional aristocracy and peerage toward middling landowners. This change was driven by the dissolution of the monasteries, which made vast tracts of land available to new buyers; the Price Revolution (the influx of American silver and resultant inflation), which drove up agricultural prices and incentivized active estate management; and the economic travails of the monarchy, which was forced to sell off lands and sell honors in a time of fiscal crisis. The result was that a class of commercially-minded landowners above the yeomanry and below the aristocracy swelled in numbers and power, growing to become an influential force in English politics at the time of the Civil War. This was a crucial factor in the outbreak of violence:

The fact that entrepreneur predominated over rentier interests in the House of Commons, was, therefore, a point of some importance. The revolt against the regulation by authority of the internal trade in agricultural produce, like the demand for the prohibition of Irish cattle imports and a stiffer tariff on grain, was natural when farming was so thoroughly commercialised that it could be said that the fall in wool prices alone in the depression of 1621 had reduced rents by over £8oo,ooo a year.

By 1680, two-thirds of the land in the counties sampled by Tawney was held by owners of four or fewer manors, while the share of the owners of ten or more manors fell to 13.6 percent. His obviously Marxist interpretation of the period has been challenged repeatedly since its publication, notably by the distinguished British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, but recent accounts of the period—centering on the institutionalist analysis of the Glorious Revolution—have co-opted large parts of the “rise of the gentry” narrative. One should beware of the attractive simplicity of this class-based social theory, but most subsequent evidence suggests that significant changes in landholding and social station did take place.