This week, I return to pure economic history, reviewing some of the seminal papers on the differences in economic performance across national boundaries. I’ve long been hoping to scan the provocative work of Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson on the role of institutions and settler mortality, and I was finally able to do so for this iteration. My skepticism was not assuaged, but I do think that their theory deserves more credit than I had previously believed. I’m still inclined to follow Branko Milanovic, however, in thinking that their papers “read like Wikipedia entries with regressions.” Luckily, I found the first Greg Clark paper (“Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed?”) to be one of the best empirical studies that I’ve seen in the discipline. If you read any work of economic history, this should be the one—it’s a paragon of concision, sharp analysis, and data collection and interpretation.

Links

Should We Abandon the Natural Rate Hypothesis?

Olivier Blanchard | Journal of Economic Perspectives | Winter 2018

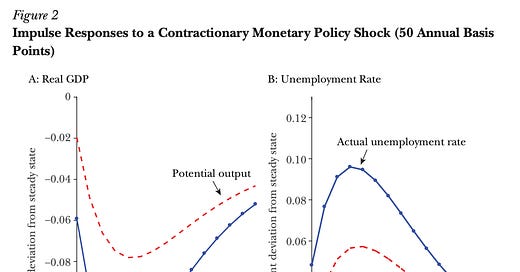

On the fiftieth anniversary of Milton Friedman’s famous presidential address to the American Economic Association, Blanchard reviews the evidence for the claim that cemented the speech’s legacy in the history of macroeconomic policy: the natural rate hypothesis, which disputed the previous orthodoxy that there was a stable trade-off between inflation and unemployment (the Phillips Curve). This theory can be decomposed into two sub-hypothesis: first, that there exists a natural rate of unemployment independent of monetary policy, and second, that attempts to keep unemployment below the natural rate will result in accelerating inflation. Though the stagflation years of the 1970s served up empirical confirmation of Friedman’s work, Blanchard suggests that the following half-century imposed a series of changes on the economic environment. His primary contention is that the natural rate is not fixed, but rather is set at different levels by shocks—when negative, a process called “hysteresis.” One such model proposes that declining investment during a tightening reduces the capital stock, thereby curtailing potential output and demonstrating a long-term effect of monetary policy. Recessions in Europe, for example, seem to have progressively raised the natural rate to higher levels, corresponding with the length and severity of each downturn. Output (the converse of unemployment), meanwhile, has remained stubbornly slow since the Global Financial Crisis, and many indicators showed a worrying labor market slack that was slow to fade. Reviewing changes in inflation before and after a series of historical recessions (associated with exogenous shocks, such as disinflationary policy), Blanchard finds that persistent changes in the level of unemployment did occur. The actual rate, in short, appeared to have followed the natural rate. There’s much more to see here, but Blanchard attributes the change to years of low, stable inflation, which dispelled the inflationary expectations that would theoretically cause acceleration.

Barry Eichengreen and Ngaire Woods | Journal of Economic Perspectives | Winter 2015

Eichengreen and Woods confront the paradoxical situation of the International Monetary Fund—an entity simultaneously suited for the critical role of referee and backstop and all but devoid of the legitimacy required to perform it. They propose that the Fund’s inability to deal with four problems—policy surveillance, lending conditionality, debt crisis management, and internal governance—has eroded the trust of member states and destabilized the global monetary system. Weaker nations, especially among emerging markets, believe with some justification that the IMF represents the interests of the advanced economies, which are prioritized in each of the above areas. Rich nations can avoid, bias, and rewrite IMF reviews; lending conditions achieve externally-imposed objectives; major creditors are privileged at the expense of internal stability; and large economies are overrepresented on the unelected Executive Board. If members believe that the Fund is a vehicle for the political and economic agendas of America and Europe, the authors argue, compliance will decline and nations resort to counterproductive policies at odds with systemic stability. The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) established a Contingent Reserve Arrangement of swap lines, for example, while the East Asian emerging markets entered into the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization (CMIM) as an alternative method of reserve pooling. These efforts are more costly and less effective solutions to the problem of exchange rate stability than the IMF could potentially provide, but are made necessary by the organization’s historical failures and dragging reforms. Eichengreen is a skilled weaver of economic history and analysis, and this article is no exception.

Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed? Lessons from the Cotton Mills

Gregory Clark | The Journal of Economic History | March 1987

Few books can have tackled as many central questions of a subfield as Clark does in this startling and lucid paper. Revolving around a comparative cost analysis of global textile producers at the start of the twentieth century, this analysis starts out to discover why poor countries, endowed with cheap labor, did not dominate the global trade, and conversely why Britain, America, and Canada—home to the world’s most expensive workforces—commanded nearly two-thirds of all spindles. Chinese labor costs were only 10.8 percent of Britain’s and 6.1 percent of America’s; even the higher prices of capital and energy prevailing in developing regions cannot, Clark argues, detract from this staggering advantage. Only after adjusting for worker efficiency can the implied profit rates in global cotton sectors conform to the historical evidence—in the highest-wage countries, workers tended almost five times as many machines as their counterparts in the lowest-wage nations. Clark disputes the claim, advanced by economists like H. J. Habbakuk and Robert Allen (and to which I am partial), that this was the result of producer choice, substituting cheap hand labor for expensive machinery to minimize costs. Only 14.5 percent of the additional Chinese workers and 13 percent of Japanese can be explained by this microeconomic process; moreover, no country exceeded British per-machine output in 1910. Saving on cotton costs (through cheaper yarns, which required more labor to repair) was similarly irrelevant, as lagging nations generally used the same materials as the leaders and were in any case overmanned in parts of the production process where quality was irrelevant. The explanation of weak developing-world performance, to Clark, is deficient worker productivity—attributable neither to experience nor education, but rather to vague differences in “local influences” that led workers to refuse the imposition of additional machinery. Adjusted for output per laborer, labor costs converge worldwide. “If, as I anticipate,” Clark concludes, “other industries were like textiles, then the major source of the underdevelopment of poor countries was the inefficiency of their labor, rather than their inability to absorb modern industrial technology.” Strikingly, the machines used in both rich and poor nations were observed to be homogenous, in spite of adoption costs (as emphasized by Allen)—productivity differences can only be tied to the workers. The source of the gap is left troublingly ambiguous, but one can still agree with Clark that his is “not a modest or an uncontroversial claim.”

The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson | American Economic Review | December 2001

This paper also attempts to explain everything, but is, as universal theories tend to be, less successful in doing so. Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (henceforth AJR) propose a unique explanation of the dramatic divergences in international prosperity: that settler mortality during the age of European colonization determined the institutions established in the conquered regions, and thus the subsequent economic outcomes prevailing in those areas. Where settlement was inhospitable, as in Latin America and the Belgian Congo, Europeans set up “extractive institutions” designed to “transfer as much of the resources of the colony to the colonizer, with the minimum amount of investment possible.” Where settlement was feasible, as in the “neo-Europes” of North America and Oceania, Europeans reproduced domestic institutions, which emphasized the protection of property rights and constraints on executives. These structures persisted into the present, underlying governance structures post-independence and dictating economic performance. Regimes derived from “extractive” institutions discourage investment and entrepreneurship, while “inclusive” institutions deliberately encourage business activity and growth. This theory is substantiated by a central instrumental variables (IV) regression, which uses settler mortality as an exogenous instrument for institutional quality (measured chiefly by “expropriation risk”), which is in turn correlated with economic success. Institutions, under this specification, explain three-quarters of the gaps in trans-national economic outcomes. There are more extant critiques of the “colonial origins” hypothesis than I will ever have time to read, let alone review, but I hope to get to some next week. For the present, I will simply note that some of the empirical evidence differentiating “extractive” from “inclusive” regimes is faulty; the channels of persistence suspect; and most damagingly, that AJR do not sufficiently dispel the potential problem of factors correlated with mortality (such as the disease environment, as Jeffrey Sachs has emphasized) themselves altering growth trajectories. Nevertheless, this is one of the most famous papers in the recent economic history literature and is certainly worth reading.

One Polity, Many Countries: Economic Growth in India, 1873-2000

Gregory Clark and Susan Wolcott | Working Paper | 2003

Clark and Wolcott return to the subject of worker productivity in an Indian case study, arguing—in contrast to AJR—that institutions are not the source of economic dynamism. The subcontinent struggled through laissez-faire capitalist and all-but-socialist regimes alike, and even modestly improved growth since 1986 predated the reforms often deemed responsible. Further, despite increasingly homogenous national policies, the outcomes of Indian states are diverging, with high-income states growing demonstrably faster than low-income neighbors. Clark and Wolcott argue that falling per capita income relative to the West was “overwhelmingly” the result of “a decline in the relative efficiency of utilization of technology in India relative to Britain and the USA.” Revisiting the evidence of the textile mills, the authors show that in 1990, Indian productivity levels—measured by spindles doffed—were less than a quarter of those achieved in America in 1959 (the last recorded figure before the task was automated). The empirical evidence is solid, but again, the explanation is less so: the absence of a “gift-giving” employment environment in India, where workers have no incentive to put effort into tasks where monitoring is impossible. A poor equilibrium thus develops where laborers expect shirking from colleagues and conform to behavioral norms.

In this case technologies that rely for their implementation on the employment relationship will be handicapped. Employees will provide little for their wage. They will be protected by the knowledge that any potential replacements will provide little also. If all around you give nothing to the employer then why should you give? Thus we can have several possible employment regimes. One where most workers voluntarily do more than they have to, and another where all workers act opportunistically.

Our idea then would be that Indian employers extract little of the labor power they pay for from employees because of employee’s unwillingness to give voluntarily what is costly to monitor.

In India, this is evidenced by the tendency for rural workers to be hired on short-term contracts with standardized wages, in contrast with the longer-term, salary-tailored contracts prevailing among Western firms. With weavers supervising only 1.5 power looms each, modern technologies rapidly become inefficient and profits are winnowed away—as shown by the persistence of the antiquated handloom sector. Clark and Wolcott admit that their theory remains “inchoate,” but it’s a major mechanical improvement over the one offered in “Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed?” Once again, however, Clark begs the question of why this cultural outcome should obtain. The answers given here, and in A Farewell to Alms, are similarly ephemeral and unsatisfying. I’ll have to keep reading.