This week’s papers touch on a range of subjects. The first examines the distributional consequences of Ghanian colonial cash crop farmings, an industry often slated for producing returns for the metropole but few for the colony. The second compares intergenerational social mobility in Communist and capitalist Hungary in an attempt to study the institutional influence on status persistence. Our third (barely an economic history paper, though published in Explorations) discusses the consequences of Muslim conquest on Middle Eastern autocracy, while the fourth and last applies a novel dataset to tracking productivity change in textiles during the Industrial Revolution (even more highly recommended).

Long-term trends in income inequality: Winners and losers of economic change in Ghana, 1891–1960

Prince Young Aboagye and Jutta Bolt | Explorations in Economic History

The economic consequences of African cash crop exports during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries remain a puzzle; Williamson, for example, has found that primary producers grew throughout the 1800s, but not as quickly as more diversified manufacturers in the “core.”1 Aboagye and Bolt examine this question from a distributional perspective. Calculating social tables and Gini coefficients for the seven decades between 1891 and 1960, they find that inequality was already high (0.4) in the former year, prior to the spread of cocoa cultivation. The subsequent four decades were remarkably stable, but following a brief decline during the Great Depression, gains made by the top ten percent resulted in a climb to .52 in 1960. By analyzing the country’s changing occupational structure, the authors find that rising wages for government employees and skilled and commercial workers (while the bottom 40 percent stagnated) were to blame; the highest earners were too small a share of the national income to significantly increase inequality.

Social Mobility and Political Regimes: Intergenerational Mobility in Hungary, 1949-2017

Paweł Bukowski, Gregory Clark, Attila Gáspár, and Rita Pető | LSE Working Paper

How much does Communism, the greatest of institutional levelers, reduce social stratification? The authors suggest, from the example of Hungary, that the answer may be “very little.” They compare the relative representation of classes of high-status (those of noble descent, ending in -y, and those overrepresented among high school graduates) and low-status (the 20 most common in Hungary and those underrepresented among graduates) surnames in educational, economic, and political elites to produce decadal mobility estimates. Social mobility rates throughout the last seventy years were low, with an intergenerational correlation coefficient of 0.6-0.8 for both classes. Descendants of the 18th-century nobility, for example, were 2.5 times more likely to have medical degrees than non-Romani. No change was observable between the socialist and capitalist regimes. The most significant alteration was of the political elite (members of Parliament), which saw drastic changes across the transition.

Muslim conquest and institutional formation

Faisal Z. Ahmed | Explorations in Economic History

One of the most intriguing literatures in pre-modern economic history is that attempting to explain the economic stagnation of the Islamic world after 1100, despite possessing advanced science and technology, literacy, and urbanization. Popular hypotheses have focused on institutions—on the inhibitions on lending and commerce imposed by sharia law or the embedding of production in central government.2 This paper, while remote from the economic consequences (“the initial step in the conjectured link”),3 uses a difference-in-differences strategy with panel data to propose a source for the adverse political environment: Muslim conquest. Territorial acquisition by Islamic states led to a centralized regime—by 5 points on a 50-point scale for the modal region—controlling a larger proportion of available land. Leaders in newly conquered regions also ruled for 25 percent longer than the modal Muslim leader, thanks to the presence of elite mamluk slave soldiers and the iqta system of compensation. The mamluks obviated the need for rulers to recruit locally and make concessions to elites, while control over land provided the military finance which European leaders negotiated at increasing costs from parliaments. Conquest, in sum, produced an autocratic equilibrium with power concentrated in the hands of a small elite. Ahmed suggests that this order persisted to the present, but this is not demonstrated in the paper itself.

After the great inventions: technological change in UK cotton spinning, 1780–1835

Peter Maw, Peter Solar, Aidan Kane, and John S. Lyons | Economic History Review

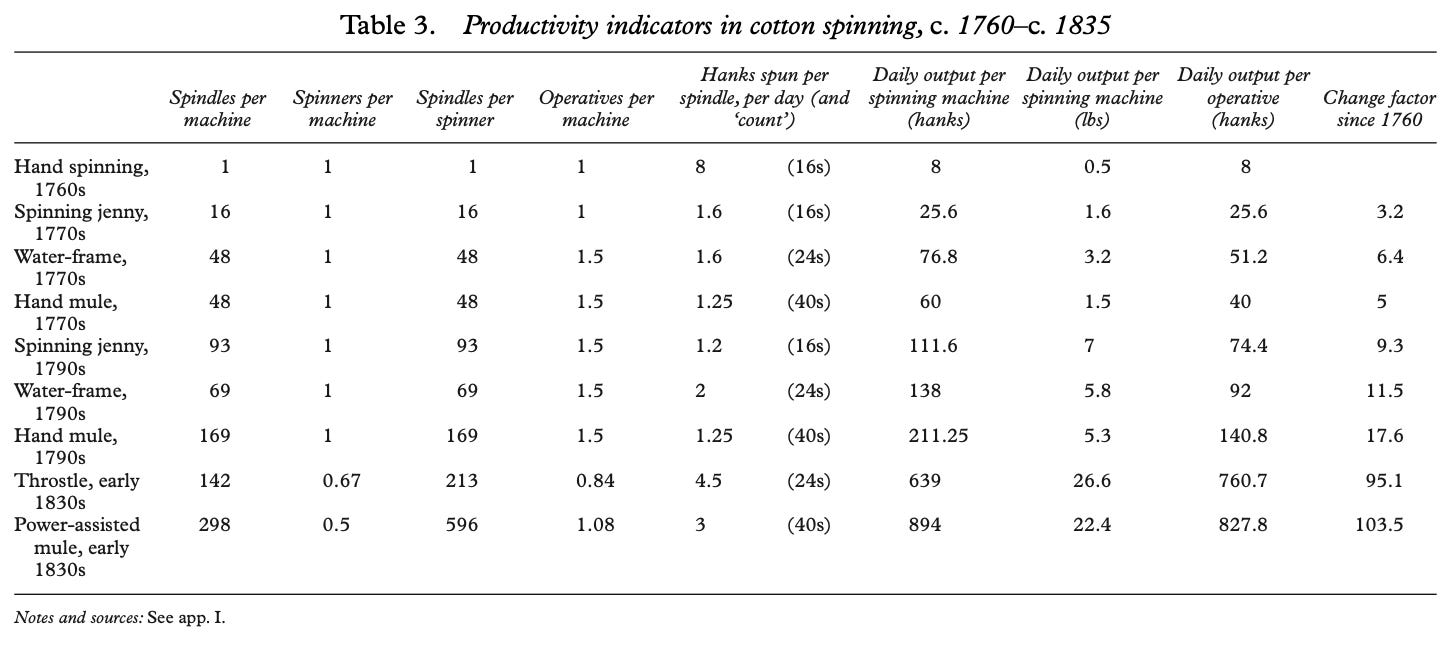

Joel Mokyr’s division of technological creativity between paradigmatic macroinventions and incremental microinventions emphasized a combination of the two forces in driving British economic growth: the former forcing breakthroughs, the latter consolidating and perfecting them. Yet the small engineering contributions can constituted the second category—responsible for much of cost-saving—remain difficult to pinpoint. The authors take a creative approach: extracting the text of 1,465 advertisements for cotton-spinning machinery published in British newspapers from 1780-1835. They document steady increases in spindlage across jennies, water-frames, throstles, and mules, with the last of these having more than doubled in size (from less than 150 spindles on average to 300, with many exceeding 400 and some in the 500-600 range). Figures on machine size and output lead them to calculate the contribution of microinventions to productivity growth in the cotton-spinning sector. They find that change in efficiency was most rapid after 1800, following the era of the “Great Inventions” of Arkwright, Hargreaves, and Crompton—implying that successive, marginal microinventions were the main source of higher output per worker and per spindle.

Williamson J, Blattman C, Hwang J. The Impact of the Terms of Trade and Economic Development in the Periphery, 1870-1939: Volatility and Secular Change. 2004.

See a favorite paper: Pamuk, Sevket (2014): Institutional Change and Economic Development in the Middle East 700-1800, in J. Williamson and L. Neal (eds.) Cambridge History of Capitalism, Vol 1. Timur Kuran’s The Long Divergence is also recommended reading.

Whether or not this sort of paper is economic history at all remains questionable. The author, by his repeated claims that it is, seems to be doubtful. Here’s his rationale: “In documenting how Muslim conquest changed institutions in conquered territories, the paper establishes a crucial precondition for other facets of medieval Muslim societies that subsequently helped shape the trajectory of long-run economic and political development in Muslim societies.” The causal chain is from conquest to autocracy to political persistence to bad institutions to economic decline—so his focus on conquest is at least three steps removed from the economic part.