From Slavery to Capitalism?

The Williams Thesis, Part II

This is Part II of my series on the Williams thesis. It takes on the (overly ambitious) task of surveying the economic history literature since 1990 on the connections between slavery and industrial capitalism.

This post is long. If you’re inclined to read just a quick summary, here’s the TL;DR.

Slavery was not essential for industrialization.

Slavery may help to explain why Britain industrialized first. Economic historians have tried to argue this in three main ways.

(1) Vent-for-surplus view: Britain’s colonial Atlantic economy furnished export markets for textiles and metalwares, which were predominantly sold abroad.

Without these exports, Britain would have suffered from underemployed resources and low productivity as labor sat idle.

Larger markets meant economies of scale and endogenous innovation in the export-facing sectors.

Without slavery, the American colonies would have demanded fewer exports.

(2) Ghost acreages (a la Pomeranz): imports of American cotton solved the supply bottleneck for the UK textile industry, in the absence of which high prices and the low quality if Indian cotton would’ve choked off industrialization.

But Indian cotton was substituted for U.S. cotton during the Civil War.

If slavery had been abolished during the eighteenth century, the counterfactual isn’t “no cotton” but “less cotton”—unlike sugar, you can grow cotton with free labor.

(3) The slave trade and Atlantic exports fostered financial services and created human capital externalities that enlarged Britain’s skilled labor force.

This almost certainly happened, but it’s unclear how big the effect was, and how much of it couldn’t be accomplished by trading with Europe.

Most empirical tests of the Williams thesis do not address (1)-(3).

Slavery is capitalism's original sin. There's no doubt that the plantation system of the Atlantic world was profitable, rationalized, and market-oriented—and that it yielded significant gains to the planter class. Planters, in turn, invested their profits back in the metropole and bought foodstuffs and manufactured goods from Britain and the northern colonies; by the late eighteenth century, most of Britain's trade in manufactures was with the Americas, and much of that relied (directly and circuitously) on coerced labor and bondage.

So slavery was important to really-existing capitalism in its infancy. But there's another question here. Could British industrialization, and thus capitalism itself, have emerged only because of slavery? And if not, did slavery accelerate early modern economic growth, or was it just incidental—a stain on the human record, but needless one at that?

Questions like these matter. If you think that industrial capitalism and modern economic growth could only have arisen in a slave-based economy, then you're making a pretty strong claim about the moral foundations of Western society—there's a causal connection between centuries of exploitation and the sandwich you're eating for lunch. As Stanley Engerman wrote in 1972, "history becomes a morality play in which one evil (the Industrial Revolution) arises from another, perhaps even greater evil, slavery and imperialism." Whereas if you think that abolition could have been accomplished in, say, 1750 with little impact on economic growth, then you've got a better case for just indicting the monsters and benighted fools of yesteryear.

To my mind, this is what the entire "contribution of the periphery" debate (of which the Williams debate is a big part) is really about. Is capitalism built on a heap of bones, or isn't it? It's not just scientific history, but also the empirical foundation for a moral debate. To talk about the role of the slave trade is to try to answer the age-old question: is Western capitalism evil? The accusatory undertone is implicit in a lot (but not all) of pro-Williams research, and a defensive one in (again, not all of) his detractors. Those are the stakes.

The Age of Solow

The publication in 1991 of Barbara Solow's edited volume Slavery and the Rise of the Atlantic System symbolized the resurrection of the "Atlantic economy" version of the Williams thesis. There's a triumphalist tone to the book—all of the essays stress, at least to some extent, the importance of European trade with Africa and the Americas, and the rare debates are mostly nitpicking about emphasis. The one "contrarian" essay, O'Brien and Engerman's "Exports and the growth of the British economy from the Glorious Revolution to the Peace of Amiens," conceded most of the field to the Williams-ites.

Nevertheless, some historians were still frustrated that their more economics-focused colleagues still ignored the Atlantic economy, and the slave trade in particular. Darity (1990) groused that neither "Nicholas Crafts (1987) nor Jeffrey Williamson (1987) nor Joel Mokyr (1987) gives even passing notice, in the special issue of Explorations in Economic History devoted to Britain's industrial revolution, to the potential relevance of Eric Williams's (1966 [1944]) hypothesis that the development of British industrial capitalism bore intimate links to the Atlantic slave system."

Darity's formula is reminiscent of Inikori's. He conveniently endogenizes technical change to market expansion, a la Smith, and even gives an ironic citation to the irascible McCloskey. Slavery was necessary for the "proletarianization" of the Americas because getting white labor there would've been too expensive, lowering profitability and presumably slowing down industrialization. Britain exploited its position as the imperial metropole to create an intra-imperial core-periphery system in which she imported foodstuffs, lowering real wages and raising the rate of return. Colonial investment opportunities also prevented profits from declining by the good old "recycling of plantation wealth" mechanism.

As with Inikori, the mechanism by which extending the market isn't really explicit; and thus reliant on Smithian technical change, Darity struggles to encompass inventive behavior that doesn't conform to, well, textile factories. I'm sympathetic to the broad concept that "doing stuff more" will lead to "you getting better at doing said stuff." But suggesting that the "wave of gadgets" can be fully explained by market extension, ignoring the agrarian, geographical, and institutional context of Britain's economy, is weak.

Solow's essay in her Atlantic System volume expands on the role of slavery in colonial development. She argues that pre-modern land-abundant economies are "more likely to stagnate than grow"; high incomes only go to farm labor, and average people may not have the means to emigrate (which assumes a capital constraint). Investment opportunities are curtailed by the inelastic supply of labor caused by the availability of free land—who'd pay rents to a landlord if they could be an owner-occupier on a big farm on the frontier? Slavery "solves the problem"—a cheap supply of coerced labor that allows Europeans to cultivate plantation crops. It's a variant of the Domar model—serfdom arises in economies with a high land-labor ratio—but used to explain extensive growth in a land-abundant settler colony.

The most important essay in the volume, though, is O'Brien and Engerman's "Exports and the growth of the British economy from the Glorious Revolution to the Peace of Amiens." I could be mistaken, but this paper, to my mind, is the beginning of what Pseudoerasmus called O'Brien's Damascene conversion to peripheralism. The authors trace the role that England's textile exports played in economic developments since the Tudors, when the country transitioned from raw wool to woolen cloth and exports made up about 4 percent of national income. By 1700, export values had quadrupled, making up 8-9 percent of national and supporting somewhere between 20 and 30 percent of the population.

Over 1697-1802, however, exports grew at a rate of 1.5 percent per annum (50 percent faster than in the long seventeenth century), and by 1802 88 percent of those were manufactured—metals, metalware, and cotton. Critically, 95 percent of additional commodity exports during this period went to North America and the British West Indies. Up to 1790, this increment occurred thanks to "autonomous foreign demand," rather than internal factors that drove innovation. In

Aside: the debate about whether foreign demand was an exogenous factor is weird, but the idea is that rising incomes abroad/access to new export markets drops new consumers of your goods upon you like manna from heaven. It's not true. As Findlay and O'Rourke (2007) point out, increasing income/number of consumers shifts the demand curve to the right, which should raise prices. But England's terms of trade fell, suggesting that biased technical change in cotton textiles increased supply much faster than demand rose to meet it.

Nevertheless, O&E raise an important point. Economists modeling the gains from trade in Ricardian terms, in which all resources are fully employed, generally find small numbers—trade just reallocates labor, land, and capital to marginally more productive uses. Autarky means that factors used for exports just go into making domestically consumed goods; for Thomas and McCloskey (1981), their famous suggestion was beer. O&E, however, adopt a vent-for-surplus model, in which land and labor are idle. If foreign consumers don't buy some additional copper plate, for example, no one will, and either prices drop through the floor or workers are unemployed. So the counterfactual output under autarky may not be, say, 20% lower in traded sectors, but 100% lower.

The only real point of "contention" in the volume as pertains to the Williams thesis is Solow's bizarre assertion that O&E don't consider slavery. She reminds the reader that the colonies wouldn't have developed nearly as rapidly without coerced labor—most of the whites were indentured servants and 2/3 of them went to plantation colonies. Sugar constituted 60 percent of British American exports to the metropole up to 1775, most Southern exports were slave-made, and many of the Northern/Middle colonies (78/42 percent) were bought by the West Indies. "The foreign exchange to purchase British goods was earned from the labor of slaves, and it was the American slave who ultimately provided the increased market for the manufactured exports of Great Britain in the eighteenth century." But this is a non-issue and I wonder if Solow was just pretending to take umbrage at something for the sake of alleviating the collection's rather uniform tone.

General Equilibrium

Nevertheless, what neither O&E nor Solow actually presents is a counterfactual analysis for a British economy unable to dump its surplus produce on plantation slaves in the Americas. There are two ways to argue about the counterfactual. First, you can make comparisons spatially, using a discontinuity in the treatment to show its effects relative to a comparison group where it was weaker/absent. That was hard to do in the '90s and it's still not clear how valid this would be. You can't easily compare countries because of the minuscule sample size and bad data; and even if you did, there were other slave-trading countries (like Portugal) that did pretty badly. The tech wasn't really there for within-country comparisons.

The other way you can do this is via general equilibrium modeling. The idea is to examine the effects of a change in prices or output in one sector on the rest of the economy—analyzing all markets in unison. Two papers attempted to do this for the triangular trade: Darity (1982) and Findlay (1990). I'll take a deeper dive into these two in the next post, which will be the wonkish econ version. For now, I give a quick summary of what Findlay does.

There are three regions: Britain, America, and Africa. Britain makes manufactures with capital and labor, the latter of which is in fixed supply, as well as a colonial raw material input, such as cotton or sugar. America exports the raw materials using slave labor and a finite supply of land, while Africa exchanges slaves for manufactured goods. In this model, the Industrial Revolution isn't endogenous, so there's no question of the Williams thesis as such being right. Instead, it's a shock to the productivity of labor and capital in Britain, which increases the supply of manufactures and the demand for raw materials and slaves. British terms of trade (export over import prices) fall, while those for America and Africa rise.

What happens if you ban the slave trade? Depends when. If you're following the Solow story, where you need slavery to develop the Americas altogether, then banning the trade in 1607—following O'Brien's counterfactual—rather than 1807 removes the elastic supply of labor needed to complement abundant land. Findlay and Solow agree that early abolition is basically akin to cutting off Britain from the New World—zero trade. No cotton supplies, no sugar.

That means high raw materials prices, which reduces profits for manufacturers. Smaller export markets also mean lower manufactured output prices, so British producers get cut with both blades of the scissors. In 1807, though, the ban on the trade didn't matter. Presumably, sometime during the intervening two centuries, the American slave population could provide a sufficiently elastic supply. There's also the implicit assumption that no output could've been derived from the Americas and that no substitutes could have been found elsewhere—that's baked into the model, which only has three regions. Anyway, the point here is that Findlay can actually show that, in the model, cutting off the slave trade can hamper industrialization. But what he can't show is that endogenous take-off is a function of the Atlantic trade. And while he echoes Solow in criticizing the Engerman-O'Brien position on "small ratios," he doesn't add much.

Darity (1992) has a famous short summary piece in the AER—"A Model of Original Sin"—where he (which surprised me) doesn't actually present a model at all, but just adds some detail to his and Findlay's. He recommends a Keynesian approach to modeling the "Williams-Rodney hypothesis", predicated on the existence of vast intersectoral linkages and multiplier effects between slave trading/planting and the British home economy. Darity thinks you should take the mercantilists seriously when they say, like Josiah Child, that colonies created jobs where they didn't exist before by hoovering up unused labor.

Backward and forward linkages abound. Wool and cotton textiles needed to buy slaves in Guinea fueled the rise of Manchester; iron tools for the planters and chains for the slavers; Bristol shipbuilding; Birmingham's arms industry (the gun-slave cycle); and even furniture and pottery, somehow. Sugar processing and tobacco, too. But only the gun case is given any magnitude, though–over 1.6 million firearms were shipped to Africa during the Napoleonic Wars. That's the trouble with this line of reasoning. Without any real data on the connections between sectors, your backward and forward linkages could be responsible for 1 or 100 percent of value added in down/upstream industries.

Two Big Books

Two major historical works tackled the slavery-development nexus at the end of the millennium. Robin Blackburn's The Making of New World Slavery (1997) concludes with a lengthy survey chapter on the contribution of slavery to the Industrial Revolution in Britain. The rest of the book is turgid, but those last 70 pages are great. Blackburn situates the Williams debate as just one part of the broader question of the 'contribution of the periphery'—starting with Marx, whose claims that "[t]he colonial system ripened trade and navigation as in a hothouse... [and the] colonies provided a market for the budding manufactures" are quoted by everyone like supplicants appeasing an angry god. He then outlines the various direct and indirect ways that slavery promoted British growth.

First, he restates the export-led growth view, noting that even the skeptics (O'Brien and Engerman) hold it. Second, he refuses to let the profits-investment channel die. He elevates the profit levels for the slave trade and West Indies plantations to show that they could have accounted for between 21 and 55 percent of British gross capital formation circa 1770, assuming either a 30 or a 50 percent rate of reinvestment and whether you choose his lower or upper bound for total profits. Critical here is Blackburn's decision to incorporate a "realization effect"—profits generated by British industry as a result of exporting to the plantations. Notably, he discards Thomas's deductions for imperial defense costs and price distortions. Blackburn claims that his findings are consistent with the original Williams thesis—that slave-trading profits "fertilized the entire productive system of the country." He notes that both the "resource increment" derived from trading profits and exports to the coercive American colonies tripled at the end of the eighteenth century.

Nevertheless, Blackburn admits that the imperial system was a wasteful, inefficient way to generate investment funds—sometimes, it even siphoned them off. He also acknowledges that the only reason mercantile profits could be transmuted into industrial development was because of Britain's prior commercialization, centered on the totally domestic emergence of capitalist agriculture. Small provincial banks, not the City of London—the proverbial octopus manipulating the imperial world-economy—were the main source of industrial finance.

So Blackburn instead focuses on alternative channels—profits were invested in agricultural improvement (but who knows how much land, and how much investment) and canals. Moreover, he tries to argue that investing in the slave trade and in textiles was kind of the same thing, because the two sectors' production cycles were complementary, and stresses the role that mercantile investment played in diverse areas—brewing, baking, candlestick-making. I'll grant that the breadth of channels that he draws up is impressive (and creative). He neglects, however, to give any idea of the magnitudes involved or to mention that only some of merchants' investible funds actually came from the slave trade itself. And if his profit figures are overstated, then those magnitudes are going to be small.

Blackburn's biggest problem kind of seems to be conceptual—a Marxisant fascination with primitive accumulation. While he says that fixed capital is less important than working capital in an effort to overcome Engerman's deflationary analysis, he then asserts that the macroinventions of the Industrial Revolution required a "capital shock" to start. No, they didn't. The technology came first, generating high rates of return from which industrialists largely financed themselves.

This brings us to Blackburn's final channel, that slavery contributed cheap raw materials for British industry. Pretty straightforward stuff—only the American plantations could provide the elastic supply of cotton guzzled by Lancashire's textile mills. Economic pressures created by the plantation system led to major innovations in productivity, including Whitney's gin. Broadly speaking, slave cultivation of cotton led to primitive accumulation across two dimensions: cheap labor for the planter and cheap materials (and thus means of production) for the capitalist.

Of course, the centrality of slave-produced cotton imports is more commonly linked to Kenneth Pomeranz. His 2000 masterpiece The Great Divergence argues that the Americas, won and worked by force, provided the critical ghost acreages that propelled Britain past the Old World's common ecological constraints. Without cotton from the American South and British West Indies, Britain would've been forced to import inelastic supplies from India or (implausibly) get the equivalent from wool by infesting the UK with sheep. Pomeranz cites Williams but doesn't mention him in the text, and ignores Blackburn.

Blackburn, understandably unaware of this coming slight, concludes:

[T]he pace of capitalist industrialization in Britain was decisively advanced by its success in creating a regime of extended primitive accumulation and battening upon the super-exploitation of slaves in the Americas. Such a conclusion certainly does not imply that Britain followed some optimum path of accumulation in this period, or that this aspect of economic advance gave unambiguous benefits outside a privileged minority in the metropolis. Nor does our survey lead to the conclusion that New World slavery produced capitalism. What it does show is that exchanges with the slave plantations helped British capitalism to make a breakthrough to industrialism and global hegemony ahead of its rivals.

The Making of New World Slavery inspired the most famous paper in the anti-Williams literature. Eltis and Engerman (2000) basically snap every arrow in Blackburn's quiver, and a few others besides. They backhandedly accuse most Williamsites of extrapolating too much from the primary source views of interested merchants and mercantilists, who were both predisposed to favor the rent-sharing colonial system and incompetent at statistically evaluating it.

Eltis and Engerman then hit the numbers. The slave trade itself was only a tiny portion of British overseas commerce; in the biggest year, 1792, 204 vessels of a cumulative 38,099 tons left British ports. That's about four a week. But in that year, according to Mitchell's historical stats, there were 14,334 ships registered in Britain grossing 1.44 million tons. So 1.5 percent of British ships and 3 percent of tonnage were involved in the slave trade—not a lot! And in any event, they argue, Portugal's slave trade was larger relative to the size of its small domestic economy, but this didn't lead to convergence with Britain. I'm skeptical about Portugal's (or Spain's, for that matter) relevance as a counterfactual, given my own research on the deindustrializing effects of Dutch Disease.

E&E also critique the "Atlantic economy" reasoning of the Solovian consensus. Compared with France, Britain's Atlantic system was not all that impressive—by 1770, the French were making 17 percent more sugar, nine times more coffee, and 30 times more indigo than the British. France's advantage widened from 1770 to 1791 with the expansion of St. Domingue, now Haiti. Sugar, they contend, was not particularly large compared with other sectors of the British economy, even including the returns to capital and labor on the West Indian plantations. You can get a sense of the magnitudes from Table 1, which compares relative industry sizes in 1805.

Sugar, moreover, wasn't a strategic industry. It was only useful as an intermediate for the refining sector, which was smaller than paper, and while it purchased consumer goods, so did everyone else of comparable size. Moreover, under the extreme assumptions used by Solow to get "large ratios"—all the profits of the slave trade and sugar dedicated to industrial capital formation, slave- and slave-shipowners refused to expand their own activities or to spend profits on consumption—banking, insurance, horse-breeding, canals, hospitality, construction, wheat farming, fishing, and the manufacture of wooden implements could all have been the critical sector!

Finally, E&E swat away Solow's argument that the Americas could only have been developed with an export-oriented plantation using slave labor—though in a slightly weird way. They argue that there was lots of unfree but non-slave labor that could have substituted for African chattels, including the Latin American hacienda system or already-existing white indentured servitude. African slavery would've been more efficient, true, but the result would've been higher prices for sugar, cotton, and tobacco, not autarky for Britain.

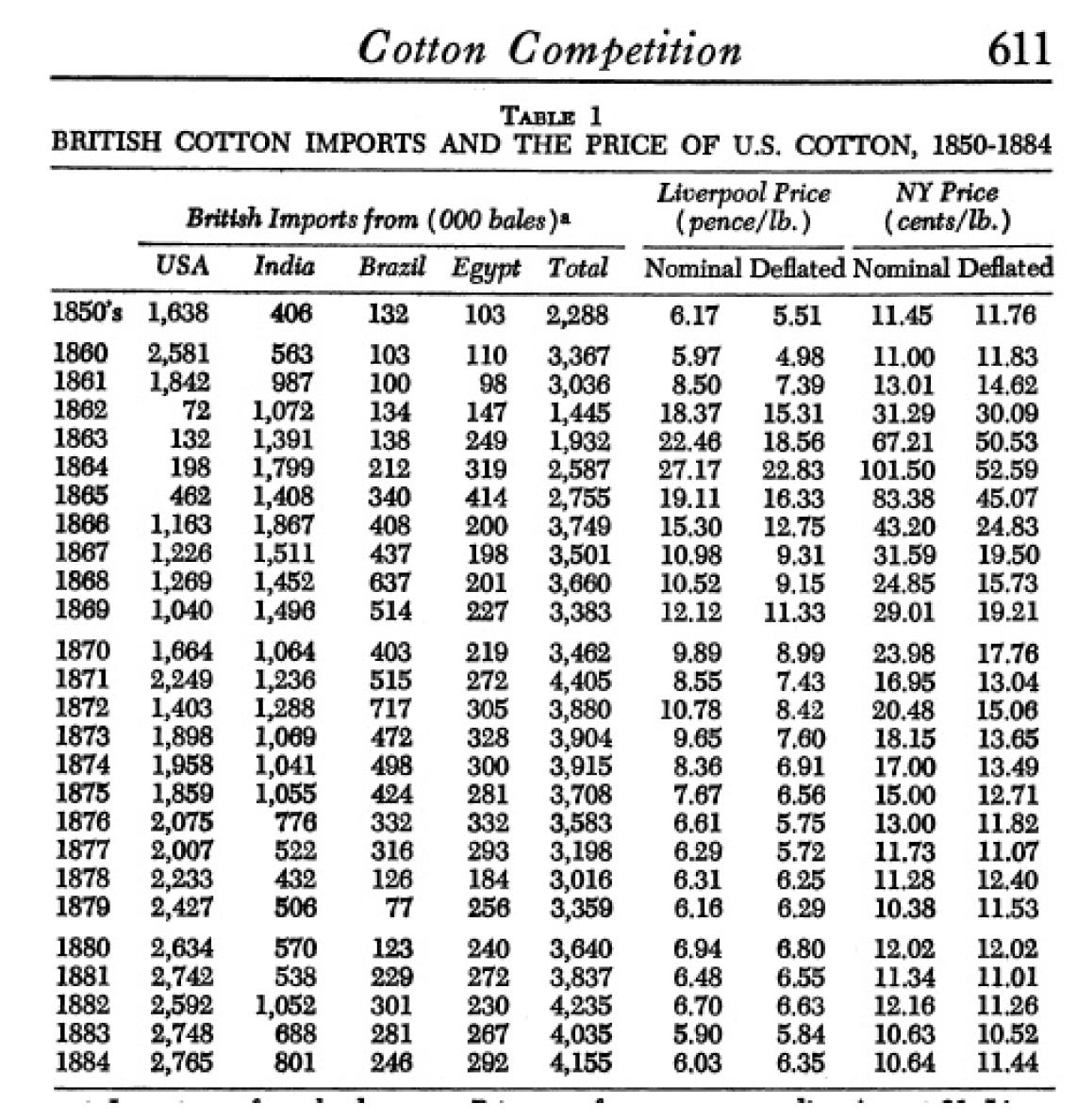

I think they dismiss the counterfactual for cotton a bit too quickly, saying that it only became important at the end of the eighteenth century. That's true. It's also true that slave-produced cotton just wasn't essential to the Industrial Revolution. During the Civil War, for example, Indian cotton was substituted for American despite its lower quality; Walker Hanlon (2014) shows that British manufacturers innovated and modified their machinery to adapt to the new source of supply.

The following chart from Pseudo shows that India expanded its output rapidly to fill the gap, such that by 1865 imports were over 80% of prewar levels. Once America came back online, British imports were well above prewar levels by 1866, and by 1880, free-labor America had finally surpassed the bumper year of 1860 in exports to Britain.

But that was in the late twentieth century, long after Britain had achieved supremacy in cotton textile production. Maybe during the nascent phases of the IR, American cotton provided a critical margin that allowed British producers to outsell Indians, and then scale up industry sufficiently to get the Great Inventions?

Still, E&E is a pretty comprehensive critique of a lot of the preceding literature, and where it offers detail, it hasn't been answered. But the paper is wanting in one big area: the vent-for-surplus and export-led-growth channels, which they basically don't address.

Joseph Inikori's Africans and the Industrial Revolution fills the gap. Subtitled "A Study in International Trade and Development", it's basically a '70s dev-econ take on Britain's industrialization as a case of export-led growth—linking the Commercial and Industrial Revolutions. For Inikori, foreign trade is a universal solvent. It changes institutions, rebalances power between interest groups, creates export markets, provides raw materials, induces the division of labor, promotes shipping and services, and spurs technological progress. Most of the "domestic" factors often cited (by people like North) are endogenous to trade. Take infrastructure provision: canals were only really useful in local circulation and getting goods from workshop to coast. Or population growth, which responded to new employment opportunities outside agriculture.

Inikori's conceptual model is a riff on classic development and trade theory: import-substitution industrialization (ISI), in which a nation tries to replace increasingly complex foreign goods with domestic versions. This process occurs in three stages. First, you must complete the "easy" step of producing consumer goods, often underneath tough tariffs, import duties, and quotas. Once the home market is saturated, you have to either produce for export or move on to stage two: producing intermediate goods, like steel. Finally, if that works out, you can finish up by making machinery, at which point you're an Industrialized Country. Inikori's thinking of South Korea and Taiwan after 1945.

Once you've got enough industry in your country, then innovation just happens—people invent by trying to solve the problems they face. It's accelerated by the formation of industrial clusters, like the West Riding woolen zone and the Lancashire textile enclave, in the hinterlands of major port regions. As Inikori writes, "overseas sales expansion and general growth of output and concentration of the industry in the region preceded the growth of technological innovation in woolen textile production in the West Riding."

Africans come in from several angles. The slave trade created massive backward linkages, from the development of maritime finance and insurance to the production of rope and copper sheathing for the ships. Participation in the triangular trade boosted British prowess as a maritime power, expanding its re-export business and entrepot trade, thus opening up new markets for British goods. However, slavery's most essential role was in permitting the "large-scale production of commodities for Atlantic commerce in the Americas" when economic pressures tended toward small-scale subsistence farming. That's all well and good, but only the former could induce the kind of regional specialization in the Atlantic basin that fueled Britain's export surge.

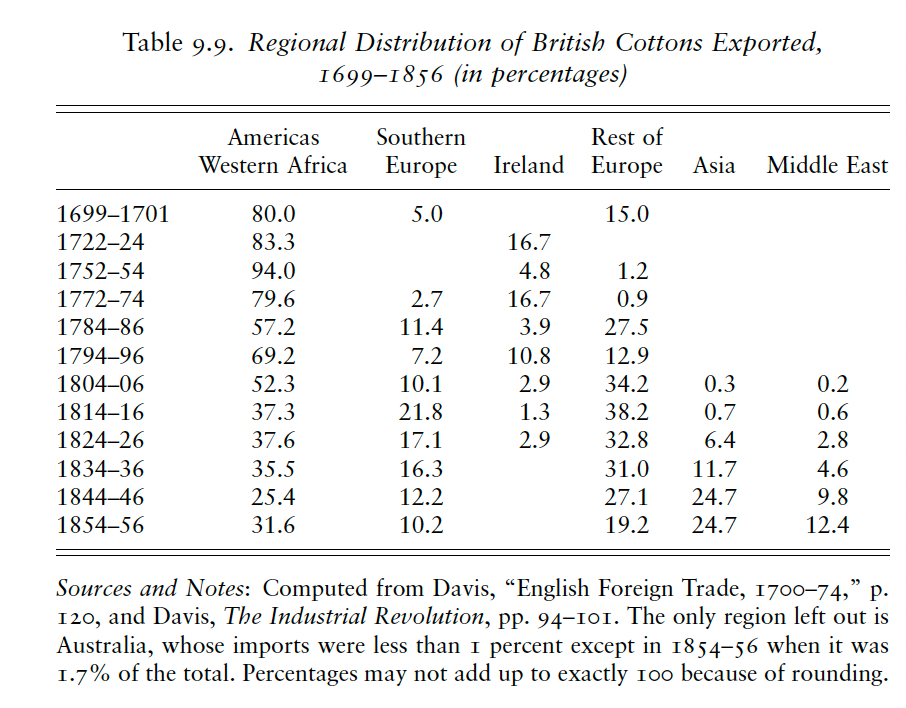

Inikori lovingly amasses statistics on the share of British overseas sales directed to America and Africa (the latter to pay for slaves, he says). Between 1699/1701 and 1772/74, increased sales of English manufactures in Western Africa and the Americas contributed 71.5 percent of the total increase in exports; from 1784/86 to 1804/06, they had a 60 percent share. Thus the purchasing power of the slave economy, Inikori claims, was central to British industrialization.

I confess to adoring Inikori's book. It's the only grand theory of the Industrial Revolution to take both British historiography and economic modeling seriously—and it's by a historian, no less! Inikori's emphasis on the commercial revolution is laudable, given that it's basically missing from/discounted in other accounts, like Mokyr's, and only briefly mentioned in Allen's. For the purposes of the Williams debate, Inikori makes foreign trade synonymous with coerced plantation labor and imperialism. To paraphrase Hobsbawm: whoever says Industrial Revolution says trade, and whoever says trade says slavery. Or a Socratic syllogism:

The Industrial Revolution was caused by trade.

Most trade was with the American plantation colonies.

Therefore, slavery caused the Industrial Revolution.

Trade Theory

The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain is a textbook—it shows the kids what the adults have been up to. Surprisingly, however, the 2004 edition contained two quite contradictory essays on the role of foreign trade in the Industrial Revolution.

On the one hand, C. Knick Harley's "Trade: discovery, mercantilism and technology" is a grouchy, old-school rejection of the "engine of growth" theory. Harley made a point ignored by vent-for-surplus theories: imports and export industries have substitutes. Engerman and O'Brien say that workers in export sectors would be tough to re-employ; Harley thinks they would have done something else, at a non-zero but not 100 percent cost. As an example, he suggests that autarky might've lowered Britain's terms of trade by 50 percent. If the share of imports in income was .125, then prohibiting trade would have lowered GDP by 50% x .125 = 6 percent.

Against Inikori's theory of trade-driven technical change, Harley writes that the "dynamic British industries would have been large even if they had not captured export markets, and there is no evidence that the expansion from trade contributed learning that would not have occurred in somewhat smaller industries." He adds, again without citation, that there's little evidence that the export sector had bigger learning dividends or that merchants saved a lot more of their income than the landed gentry.

Harley adds that the eighteenth-century British empire wasn't particularly large or prosperous compared with the French, whose Saint-Domingue plantations would have outcompeted Jamaica's without protection, or the Spanish and Portuguese. French trade to the Caribbean grew faster than English, while French merchants controlled the re-export trade for sugar in Europe. At 10.5 million inhabitants, Spanish America was a much larger export market than British America, which with just 1.5 million was about the size of Portuguese Brazil.

Harley disregards much of the existing literature on the Williams thesis, writing that "Williams’s view is now seen as overblown and the slave trade as not exceptionally profitable." In response to Solow (1985), he notes that income from wealth was equal to half of Britain's GDP, against a miserly 1.5 percent from the slave trade. And he happily cites O'Brien (1982) on the peripherality of the periphery against Wallersteinian claims about the role of an Atlantic "world-economy." That last bit is disappointing, given that O'Brien himself had long since moved on.

The essay's main attack on Inikori, though, is simply to deny that trade was essential to the Industrial Revolution at all. Yes, trade "enhanced" and "stimulated" specialization and the division of labor, but there's no causal link to modern economic growth. Instead, technological change made exports cheaper, and British industry won export markets as a result. However, that's not a death blow to Inikori or Engerman and O'Brien.

In many ways, Findlay and O'Rourke's Power and Plenty feels like a reaction to Harley. In their forceful chapter on "Trade and the Industrial Revolution," they decry the use of "Harberger triangles"—multiplying a fraction by a fraction to get a smaller fraction—to make small ratios arguments, as we saw Engerman (1972) do in the last essay and Harley do just now. But the authors also agree with Eltis and Engerman that the original Williams thesis, based on Marxist capital accumulation, is equally wrong.

Findlay and O'Rourke are economists, schooled in the new trade and growth theory of the 1980s and 1990s. They argue that most of the disagreement about the role of the foreign sector reflects "inappropriate theoretical frameworks." That feels charitable, and the ultimate cause of modeling choices has, as we've seen, been ideological. Instead, they propose a revamped version of Findlay's 1990 general equilibrium model to study a neglected counterfactual: "what would have happened to the Lancashire cotton textile industry if there had not been any British colonies or slavery in the New World[?]"

We've already discussed the basic structure. The model "predicts" an expansion of British manufactured exports as a result of technological shocks, some of which are needed simply to pay for raw materials. This obviously happened, and cotton imports exploded: in 1791, Britain imported 189,000 pounds of raw cotton; in 1801, 21 million pounds; in 1810, 91 million. American trade not only supplied crucial raw materials—over 80 percent of which were produced by Africans during the 18th century—but also stopped the prices of British textiles (churned out in increasing quantities) from falling faster than they would have done in a closed market. Thus any given increase in supply led to a greater rise in output and a smaller decline in price than would have taken place in a closed economy. As it stood, 60 percent of the cotton sector's output was exported in 1815. Maybe that could've been absorbed by the home market... but it would've been at a much-reduced price.

Findlay and O'Rourke also endogenize technical change to international trade. The high fixed costs of technology discovery and adoption can be amortized across more units in a larger market, lowering average costs. If, as Desmet and Parente (2006) show, larger markets make firms' demand curves more elastic, then any given innovation that reduces prices—like an improved textile machine—leads to greater increases in output than in smaller ones. Elastic supplies of inputs are also critical: if you can't actually buy cotton, you're sure as hell not making a machine that uses it.

The main message in Findlay and O'Rourke is not that slavery caused the Industrial Revolution. They're actually trying to show that trade and British imperialism mattered. But as Inikori showed, basically all of the cotton sector's output was going to the Americas (including indirectly via Portugal to Brazil) and Africa during the eighteenth century, at least until Europe picked up some of the slack after the American Revolution. Fustians, an early cotton-linen mix, grew up on exports to Africa and the American slave plantations. And they still appeal to the Atlantic System as an integral part of the British economy—remove one piece (slavery) and the entire scheme might wind down.

Deirdre McCloskey took issue with everyone in her 2010 book Bourgeois Dignity. It's basically an all-out attack on every major theory of the Industrial Revolution except her own—and that includes vent-for-surplus, trade-as-engine-of-growth, and the Williams thesis.

BD is, in part, a reaction to Power and Plenty, which had both come out three years before. McCloskey rightly argues that cotton could be grown without slavery. By the 1870s, prior to the imposition of Jim Crow and after abolition, the United States was producing 42 percent more cotton than in 1860. The question, of course, is whether this was possible when the Americas were being settled in the first place—when the costs and risks of setting up as a worker across the pond were high.

She makes some simple cross-country comparisons of countries with empires that did badly (Iberia) and with no empires that thrived (Scandinavia, Germany, Austria). But I simply do not understand her argument that "if Manchester had been the right place to spin cotton before the invention of air conditioning, then European events would have put it there, regardless of whether Britain won at Plassey or Quebec or Trafalgar or Waterloo." Britain's early preferential access to and development of the Americas helped to create her comparative advantage in cotton textile production. As Berg and Hudson (2021) point out, the skills of British artisans and engineers were at least partly endogenous to the raw material supplies and export markets that allowed them to work on, well, textile machinery!

The end of the 2010s was a bumper period for "big books" in economic history. Joel Mokyr's The Enlightened Economy devotes several pages to attacking the various iterations of the Williams thesis. He acknowledges that trying to cultivate cotton with free white immigrant labor would've been a lot more expensive than with slaves, but responds that this was only true of cotton. Few other critical sectors, least of all ironworking, were so heavily reliant on New World, slave-made raw materials.

Harley (2015) is also a reaction to Findlay and O'Rourke. He turns their trade-theoretic reasoning against them. The North American settler colonies, not the Caribbean, were the crucial buyers of British manufactures. The fact that American shippers entered new markets—e.g. East Asia—after independence (when they were prohibited from trading with the BWI by the Navigation Acts) shows that the Thirteen Colonies were not reliant on exports to the West Indies to earn foreign exchange. Population growth in New England, Harley adds, was probably independent of trading opportunities—who wouldn't be enthralled by the prospect of free land?

Harley also defends his Harberger triangulation—it's just math!—and calculates that if British exports were 45% of manufactured output, 55% of that went to Africa and the Americas, of which 60% went to the US and British North America, then the Numenorian destruction of the colonies would only have reduced national income by 8 percent and industry by 1/4. He adds that Findlay's 1990 general equilibrium model is very simplistic given the small number of goods and sectors and that it doesn't actually say anything about dynamic effects, because it's also static.

Human Capital

Harley, however, did not write the "international economy" essay in the 2014 edition of the CEHMB. Instead, the honor fell to Nuala Zahedieh, a historian with Williamsite leanings. Zahedieh invokes Wallerstein in discussing the core-periphery relationship between Europe and its colonial possessions, particularly the fact that "core" industries imply large human capital spillovers and up/downstream linkages for the economies that develop them. As a consequence, simply removing a line of trade, a la Harley/O'Brien, might result not only in the loss of that sector's aggregate exported output, but also detract from other nearby firms sharing its skilled labor or purchasing its cheap intermediate goods. Zahedieh also emphasizes the role that violence and mercantilism played in setting up and defending the Atlantic slave system, which led to this human capital deepening.

Zahedieh's views are probably best illustrated via her 2021 debate with Joel Mokyr over his "millwrights & mechanics" theory of the Industrial Revolution. Mokyr had published a synopsis of his views through the transcript of his Keynes Lecture—"The Holy Land of Industrialism"—in the Journal of the British Academy. The piece stresses the role of upper-tail human capital, particularly the skills of artisans and millwrights, in catalyzing British industrialization. Machines need adept makers. Zahedieh's response tries to link the "skills" argument, along with the role of applied science, to slave-based American trade. For Zahedieh, the supply of skills and the demand for useful knowledge are endogenous to the foreign sector. Trade, for example, increases the demand for accurate precision instruments, particularly clocks, used to measure positioning at sea.

Trade also sparks innovation in sectors exposed to the Atlantic economy, especially in metalworking. Zahedieh (2021) argued, by studying the accounts of the London smith William Forbes, that the copper industry was inextricably linked with slave-made sugar, which had to be boiled and refined in works requiring copper equipment. This sector's expansion had spillover effects for sectors nearby in geography and the supply chain, including reverberatory furnaces and (much, much more speculatively) the steam engine. She also links much of Britain's inventive activity during the late seventeenth (curiously, not the eighteenth) to colonial commerce. Ultimately, navigation, sugar, and slave cotton expanded the market for useful knowledge and UTHC skills that could be applied to other sectors of the economy.

Berg and Hudson (2021) make similar points in their reply to Mokyr. Arguing that "the whole question of short-lived British industrial primacy can only be addressed by invoking an external, though far from independent, economic stimulus," they attribute it to learning-by-doing externalities in the "catchment areas" of ports participating in the Atlantic trade (shades of Inikori). They emphasize a flexible, skilled, low-wage labor force that could be swiftly adapted to new export industries and product/process innovations resulting from uniquely American raw material imports. The point, though, is that looking at the straight-up contribution of the Caribbean to British output is misguided. If you cut Britain off from American trade, you'd lose not only the raw production, but also the presumably vast innovation and human capital spillovers in upstream and downstream sectors.

These spillovers are difficult to quantify, and no one (to my knowledge) has actually tried. So if you're a young, enterprising economic historian with time on your hands (wait, like me!), this would be something I'd be very interested to see. As it stands, however, we've got no idea how American trade externalities compared with those fostered by other industries, and how replaceable they were by commerce with free-labor colonies/states.

Interlude: The New History of Capitalism

At this point, you're probably wondering: what happened to Beckert? Beckert, after all, wrote a long book called Empire of Cotton in which he argued that the rise of the West was predicated on the exploitation of the Rest, specifically through the channel of enslavement and the production of raw materials. "War capitalism" meant the conquest of the Americas for cotton cultivation by slave labor and the forcible opening of foreign markets for textile exports; this terrible and evil regime, he says, transitioned to industrial capitalism at home while retaining its imperialistic elements abroad during the nineteenth century. It all sounds very Williams/Wallerstein/Inikori-ish.

Sadly, Empire of Cotton is a fairly incoherent book—and it's the most coherent and UK-focused of the "New History of Capitalism" literature, which tends to be even more jumbled and US-centric. As Burnard and Riello (2020) point out, distilling the superiority of the British Empire to "excessive brutality" makes industrialization analytically intractable, obviating the political economy and efficiency of Britain's administration and traders, and making no distinction between international and intra-imperial trade.

Burnard and Riello add that cotton wasn't actually central to industrialization until the early nineteenth century and that until that point, it was the West Indies, not the American plantations, that supplied it. Without it, they believe that it's entirely plausible for Australia (wool) or Russia (flax) to have offered up the raw materials for industrialization. They aren't extremely lucid on this point, but they make one important note—both NHCs and economic historians often conflate several questions:

What caused the Industrial Revolution

Why was the Industrial Revolution British

Why did it happen during the long eighteenth century?

Slavery, then, did not cause the IR, in the sense of ensuring that it happened somewhere. But it probably explains where and why it happened (i.e. 18th c. Britain)—which is sort of tantamount to saying that it caused the IR.

Other recent surveys, like Wright (2020), appear to agree on this point. There would probably have been an Industrial Revolution without slavery, but it would've happened later, and maybe not in Britain. Wright argues that sugar plantations in the New World could not have been cultivated without slavery, thanks to the physical dangers of the work, which free men all but refused to do. He cites many of the old arguments about the importance of market extension, adding that Lewis Paul's roller spinnning machine of 1738 was a direct consequence of international competition. He also contends that "economic infrastructure" benefited from trade—port cities developed services industries, the productivity of shipping (a "revolution of scale") improved, "long credits" were extended by longshoremen and warehousemen, and the cotton sector had gotten large enough to support a specialized machine tool industry. Wright also cites Hudson's argument that trade promoted the integration of national money markets, which in turn supplied the credit for both foreign and internal trade.

"By 2014," writes Wright, "the transformation of expert opinion seemed all but complete." He disavows the claim that slavery "caused" the Industrial Revolution, but still says that "the slave trade was part of an interdependent imperial system, whose expansion underlay the sustainability of the industrial revolution." Which is basically dodging the question. If you don't think that there is an alternate universe in which there is an Industrial Revolution without slavery, then it is a cause! It's more than a little surprising to me that historians like Wright and Hudson won't own it.

What do we know about slavery and capitalism?

Should we agree with Wright and Hudson? Is it reasonable to think that slavery was "essential" to the British Industrial Revolution?

Far from it. First, no one has successfully answered Eltis and Engerman's arguments about the non-strategic nature of the sugar industry, much less the older Thomas and Bean/Coelho critique about wealth transfers from Britain to the plantations.

Here's a plausible story about slavery's role in British industrialization. Following Solow, I think it's plausible that, without slavery, New World agriculture would have been oriented more toward yeoman farming than cash crop plantations. This would have meant less trade between the colonies and the metropole; even though imports by free and non-free colonies were in reality similar, the free colonies paid for their imports by exporting food and timber to the slave colonies. Sugar, for which the British had high levels of demand, thus became important for backstopping purchasing power in the Americas with which to buy British exports of textiles and metalware. How important sugar actually was, though, is not precisely clear—no one has successfully estimated the counterfactual.

During the eighteenth century, cotton was becoming increasingly important to Britain, and a large fraction of its output was exported. Market size created economies of scale and also directly promoted technical change, as firms could amortize the fixed costs of invention across a greater range of units sold. It's plausible to think that some of the "great inventions" in the textile industry were in some way responses to opportunities for foreign sales. Just how many has not been demonstrated. And the Findlay (1990) model is not sophisticated enough to tell us about counterfactual output and productivity in the cotton sector without slavery.

However, Clark et al. (2008, 2014), using a computable general equilibrium model, do analyze the response of sectoral output and TFP to partial and full autarky. To their surprise, they find that cutting off trade with the Americas in 1760 would have decreased total welfare by only 2 percent—and by only 1.6-3.6 percent in 1850. Cotton textile output would have declined only slightly, by 1.1 percent, and by only 8 percent in 1850. It doesn't seem plausible to say that a textiles market 90 percent of the size of the actual one would have had drastically lower rates of innovation.

The rest of the world was much more important; cutting off ROW trade would have decreased real incomes for capitalists and workers by 7.9 and 10.6 percent, respectively. These figures should be treated with some caution—they are static welfare losses, for one, and the model is still pretty simplified, including only five sectors and "the rest of the economy." Nevertheless, they're the best estimates available about the counterfactual importance of the Americas—and they do really hurt an Inikori-Williams-type story. Indeed, we can assume that the effect would have been much more moderate, given that there would have been some trade with the Americas, especially cotton exports, which could have been produced (as both Wright and Blackburn agree) with free labor.

What about other kinds of production externalities? The development of financial services, a machine-tool industry, and the cultivation of pools of skilled labor were all probably boosted by the slave trade and the plantation economy. No doubt they were important, but neither Zahedieh nor Berg and Hudson actually give any evidence as to their magnitudes. We don't need any more studies showing how these links could have worked—we need precise quantitative counterfactuals with which to assess the impact of an early abolition. Banning the slave trade in 1807, for example, clearly didn't severely damage Britain's status as a global mercantile power par excellence—indeed, Britain subsequently specialized in the provision of financial services.

The best argument you can make, I think, is that the British Atlantic empire of the early eighteenth century helped the metropole to realize latent comparative advantages. Cheap cotton and large sugar-funded markets in the New World helped Britain to expand export industries, building up scale economies, a financial services sector, and pools of skilled labor. Slavery massively boosted the import demands of the American colonies at an early stage, increasing their dependence on exports from the metropole. British industries, which were becoming increasingly export-oriented, could be protected and groomed on captured colonial markets before taking on the rest of the world—a terrific first-mover advantage. Countries lacking this internal imperial specialization could not catch up.

Even if all that were true, slavery can't explain everything. Why was Britain such a successful colonial and commercial power during the seventeenth century—a status that enabled the consolidation of the slave-based Atlantic economy? Why did Britain succeed initially in exporting to Europe even before the rise of the imperial system? How important was cotton anyway?

And the Williamsites still have questions to answer. Why didn't the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 do the damage that a Findlay or a Hudson-Zahedieh explanation would predict, given that industrial capitalism was still in its infancy? Why was the U.S. plantation economy easily able to adapt to free labor after 1865, when it supposedly would not have been in 1765? Was cotton really that important, if it only boomed after 1780 and could be produced using free labor with comparative ease? Did Britain have to produce it at all?

These are empirical problems that the literature can and must try to solve. It probably won't—we'll probably see more papers by the same old scholars saying the same old things—but there's reason to hope. Economists have taken an interest in the Williams thesis of late; Ellora Derenoncourt (2018), for example, analyzed the connection between slaving voyages and British city growth. And Heblich et al. (2022) argue that slaves, which were highly collateralizable, encouraged capital accumulation and spatial agglomeration. They show in a dynamic spatial model that slavery increased national income by 3.5 percent. We’ll dig into the mechanics of these two papers next time.

Economic historians can do a lot more to make convincing arguments in either direction. Right now, the balance is probably weakly in favor of Williams, but the effect size, if it exists, looks modest. It’s not clear that slavery was "indispensable" to industrialization, or even that it provided the essential margin that advanced Britain ahead of its European rivals.

This is great. Early on there seem to be some missing sections and typos, at least in the Substack app.

What an excellent analytical overview, should be in the textbooks!