Is there still life in the Military Revolution?

War, Technology, and State-Building in Early Modern Europe

I am currently mired in the trenches of math camp somewhere on the shores of Lake Michigan, surviving on a PhD stipend and the ration tins I stole from the MBA students. With first-year classes impending, I likely won’t be able to write much over the coming months, but I hope you’ll still consider supporting the publication by subscribing.

Early modern Europe was an exceptionally violent place. The historian J. R. Hale once wrote that "[t]here was probably no single year... in which there was neither a war nor occurrences that looked and felt remarkably like it" (Hale 1985, p. 21). During the horrific century of 1550-1650, the Great Powers—England, France, Austria, Sweden, Brandenburg, Russia, and Spain—were at war more than three-quarters of the time. This paroxysm of brutality culminated in the Thirty Years' War (1618-48), in which as many as eight million people, the vast majority civilians, died of massacre, disease, and famine. Fields were burned, stores plundered, and towns erased from the map. No place was truly immune; even England may have been at war in over half of years between the Norman Conquest and the Congress of Vienna.

Yet Europe's internecine struggles ended not in anarchy and poverty, but in industrialization and empire. Western Europe, the site of so many sieges and sacks, was a rapidly-growing commercial hub increasingly capable of projecting power overseas. Historians, economists, and political scientists have long been transfixed by the obvious question: what relationship did Europe's brutal past have with its subsequent rise to 'greatness'?

Perhaps the most influential interpretation of European military history is the "military revolution" thesis, first promulgated by Michael Roberts in 1956. Roberts argued that the exigencies of the early modern warfare led Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden to adopt Roman linear formations of shot-armed infantry, supported by cavalry charges and light field artillery. These tactical innovations required better-trained and disciplined soldiers to execute the new maneuvers, leading to the general adoption of drill, uniforms, and large professional armies organized into small, standardized units commanded by capable officers. The increasing size of armies, in turn, drove the financial innovations that led to state formation in early modern Europe.

Roberts' essay inspired and anticipated much subsequent historical work on the relationship between European Great Power conflict and military innovation. The basic concept shows up in books by authors like Paul Kennedy, William McNeill, and Jared Diamond. But the ‘military revolution’ really came into its own in the writings of Geoffrey Parker, whose book The Military Revolution extends Roberts’ arguments into an explanation of European imperial success. The Roberts-Parker thesis merged with ‘bellicist’ theories of state formation to create a dominant paradigm in modern economic history. A characteristic example is Philip Hoffman's Why did Europe Conquer the World? (2016), which argues that learning-by-doing from constant military competition gave Europeans a comparative advantage in war-making that permitted imperial expansion during the early modern period.

Yet other historians, many adopting global and comparative perspectives, have made strong and compelling critiques of the 'military revolution' thesis. Tonio Andrade (2016), for example, suggests that East Asian nations maintained military parity with the West from 1550-1700. J. C. Sharman's recent Empires of the Weak, meanwhile, argues that the 'military revolution' tactics and technologies that characterized internal European conflicts were absent or unuseful abroad. He contends that such overseas imperial success as was achieved prior to the Industrial Revolution should be attributed to indigenous political conditions and private adventurers. Moreover, he takes issue with the learning and selection models of technical change embodied in the ‘bellicist’ research programme.

This is the first of what will become a series of posts evaluating the "military revolution" thesis advanced by Roberts and Parker. That thesis has two parts:

Interminable warfare led European polities to develop increasingly expensive technologies and tactics for conquering their neighbors. Larger, better-equipped armies forced states to build up their fiscal systems or risk subjugation by those who did. The result was the characteristic 'national state' of the late eighteenth century, which combined an intrusive tax bureaucracy with extensive sovereign borrowing.

The key technological, organizational, and tactical innovations of the classic 'military revolution' phase allowed Europeans to seize territory overseas, from Acapulco to Beijing.

Here, I focus on the domestic portion of the argument—evaluating whether military competition led to larger, better armies; bigger, bloodier wars; and stronger, more effective states. I'll argue that:

The ‘military revolution’ thesis gets many of details wrong; for example

The vaunted innovations in infantry tactics emphasized by these were not limited to 1560-1660 and weren’t even as useful as argued.

Artillery-infantry-cavalry combinations didn’t work as seamlessly and Roberts and Parker assumed—blowing holes in enemy lines with cannon and riding through with cavalry was as much a myth in 1614 as in 1914. .

Fortresses could hinder as well as help state growth and centralization.

Some key aspects of the ‘military revolution’ are correct, especially that

The 'artillery fortress' contributed to army size and state expansion, though less than Parker emphasized.

Army sizes did expand as a result of interstate warfare in (but not exclusively in) the 'Roberts century' 1560-1660, and this growth was a primary impetus for the development of the fiscal state

War wasn't the only cause of state growth, and in turn politically-motivated centralization and the rise of absolutism also enhanced military prowess.

The 'military revolution' is better understood as encompassing the centuries-long co-evolution of military technology/tactics and political organization that resulted (under the duress of military competition) in the eighteenth-century fiscal-military state (rather than any one sharp discontinuity).

First, I'll describe the historiography of the 'military revolution' thesis. Second, I'll examine the major lines of criticism mustered against it. Finally, I lay out a few scattered thoughts on what to make of the literature.1

The Case for a Military Revolution

Roberts's manifesto, entitled "The Military Revolution, 1560-1660" (1956), argued that the late Renaissance witnessed four changes to the so-called ‘Western way of war.’ On the one hand, these innovations were fundamentally solutions to the classic problem of infantry tactics: how to combine close engagement with missile fire. But the ‘military revolution’ was also a response to the recent technological revolution in firearms—or rather, to its deepest flaw: the early modern firearm seemed promising but still wasn't very effective.

In the late middle ages, Roberts, argues, large-scale infantry engagements were conducted by vast squares of pikemen (the Spanish tercios). Though small-caliber firearms appeared on European battlefields in the fourteenth century, they were so cumbersome (heavy, slow, unreliable) and expensive that they were little used until the last decades of the fifteenth. Gradually, and especially after the 1550s debut of the musket, fire infantry began to displace other foot soldiers. The pikemen remained; but while the pike square was proof against cavalry attack, it was vulnerable to long-range fire by artillery and handguns. The solution was to add gunners to pike regiments -- in proportions that increased until the gunners outnumbered the pikemen.

One problem remained: the low rate of fire (about one volley every two minutes) offered by practically all early modern handguns. Thus an infantry formation would only be able to fire once at an onrushing cavalry charge. The innovative Dutch commander Maurice of Nassau devised a solution. He restored the Roman practice of linear formations, drawing his men up in thinly-packed ranks (at most 10 men deep) of long lines. The first rank would fire, then retire to the rear to reload; then the second rank, now at the front, would unleash its volley and then perform the same maneuver. By rotating through lines, a Maurician army could theoretically sustain an almost continuous barrage.

Maurician tactics were demanding of the average soldier, now tasked both with performing coordinated actions with his comrades and standing firm in the face of enemy fire. The panacea was drill: practicing march and countermarch maneuvers. To facilitate this, Maurice divided his forces into smaller units and increased the ratio of officers to men. Companies of 250 with eleven officers were reduced to 120 men with twelve officers; regiments of 2,000 were replaced by battalions of 580. The diary of Anthonis Duyck, a member of the Dutch general staff, reveals a life spent constantly on exercises, supervising troops as they practiced forming and reforming ranks and marching in formation. These motions were codified by Maurice's cousin John in an illustrated manual that sketched out how to use key infantry weapons. In 1599, Maurice also received sufficient funds to equip the Dutch army with firearms of standardized size and caliber. Standardization of uniforms followed.

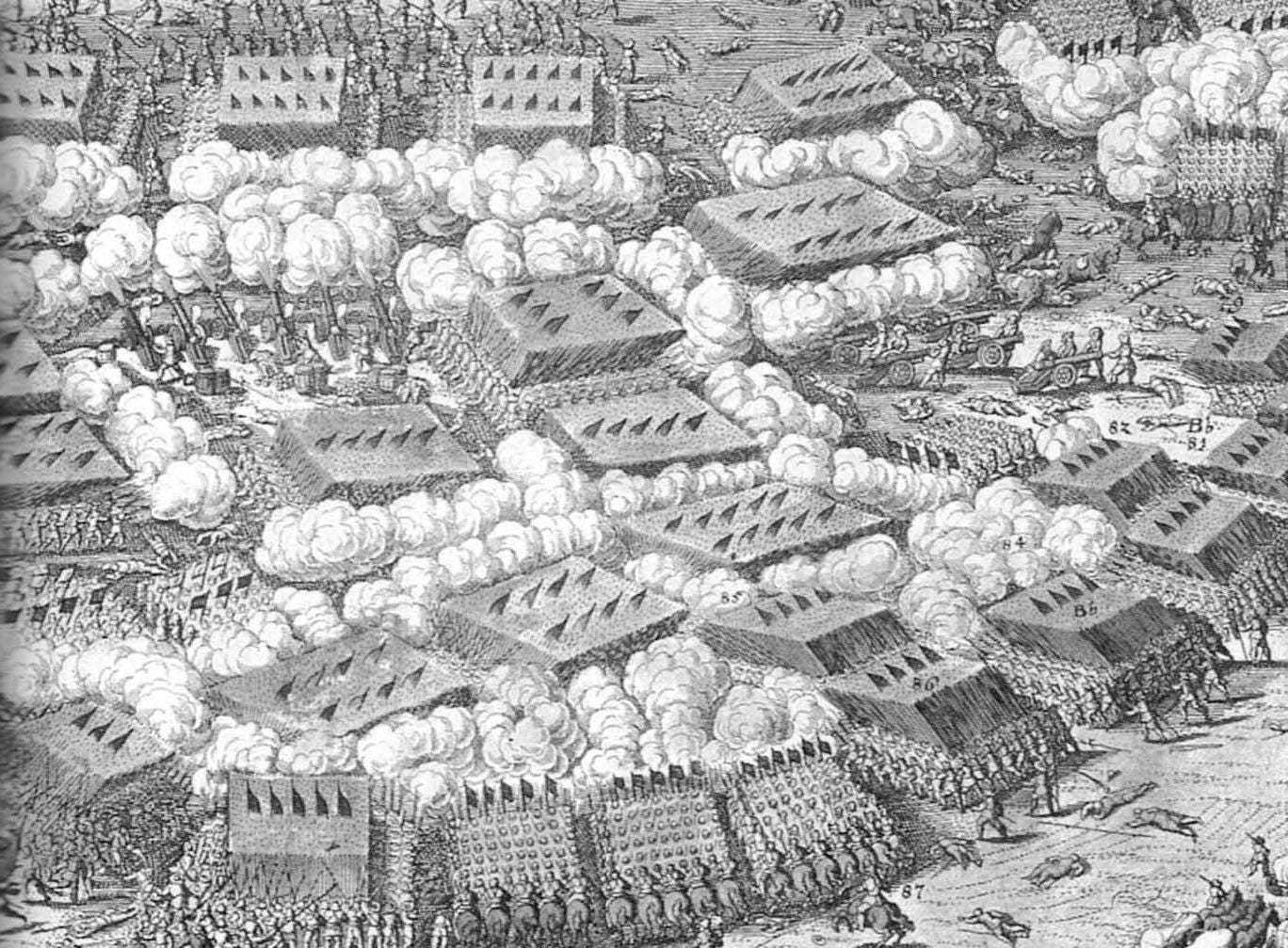

It was not the Counts of Nassau, however, but rather Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, who translated the 'revolution in tactics' into battlefield success. Thanks to extensive drilling, he improved his forces' rate of fire until only six ranks were needed to maintain a continuous barrage. To the Maurician infantry he then appended two key innovations: a massive battery of field artillery and the cavalry charge. Where the Dutch had brought just four field guns to the battle of Turnhout (1597), Gustavus carried 80 (standardized on three calibers) into Germany in 1630. And where German horsemen had tended to skirmish with pistols and carbines from a distance, Gustavus had his Swedish cavalry charge enemy lines with swords drawn. The apotheosis of the new tactics came at the battle of Breitenfeld, outside Leipzig, in 1631, when an Imperial army under Count Tilly—drawn up in square formations—faced a Swedish force of similar size, but with a larger artillery train. After two hours of fighting, nearly half of the Imperial contingent had been killed, wounded, or captured, with much of the remainder succumbing over the following days.

The 'revolution in tactics' led to a 'revolution in strategy.' Better troops could follow more complex strategies involving multiple field armies and wouldn't run away during decisive battles. Gustavus Adolphus pioneered the concept during his German campaigns. But this necessitated much larger deployments of men to execute; thus the third pillar of the "military revolution" thesis was an acceleration in the growth of armies. The Dutch army more than doubled in size, growing from 25,000-33,000 men in 1600 to 70,000 in 1625. The Swedish army, meanwhile, exploded from 15,000 men in 1590 to a peak of 150,000 in 1639—equal in size to France's and nearly as big as Spain's.

But larger armies, whether mercenary or conscript, were expensive. Paying for expansion and professionalization placed enormous demands on the primitive financial systems of European states. Rulers met these challenges by extending executive authority and increasing tax burdens (as well as corvees), which in turn required the creation of a new bureaucracy of administrative officials. The men had to be recruited, equipped, paid, and fed. They needed barracks, clothes, and roads—outside Italy, there weren't enough roads capable of moving a large army, its supply train, and artillery. Thus, for Roberts, the modern centralized nation-state originated in international military competition—helping to set a paradigm for Charles Tilly, Michael Mann, and the rest of the 'bellicist' school of state formation scholars.

Roberts' thesis, which melded military with social/political history, was immediately popular among historians. George Clark, for example, borrows the 'military revolution' for his War and Society in the Seventeenth Century (1958). It wasn't until 1976 that Geoffrey Parker, in "The 'Military Revolution, 1560-1660'—A Myth?", offered a sustained critique. Parker did not reject the Roberts thesis; instead, he argued that the military revolution should be pushed back to 1530 and that it should include innovations in Italy and Spain. "Many of the developments described by Roberts," Parker wrote, "also characterized warfare in Renaissance Italy: professional standing armies, regularly mustered, organized into small units of standard size with uniform armament and sometimes uniform dress, quartered sometimes in specially constructed barracks" (Parker 1976, p. 38). The Habsburg Spanish armies, meanwhile, were not the dilapidated relics described by Parker, but rather early adopters of gun warfare, infantry organization, and administration (at least outside Spain). While increasing army sizes provided some of the impetus for state transformation, that trend had preceded the Maurician reforms and could thus not be attributed to them.

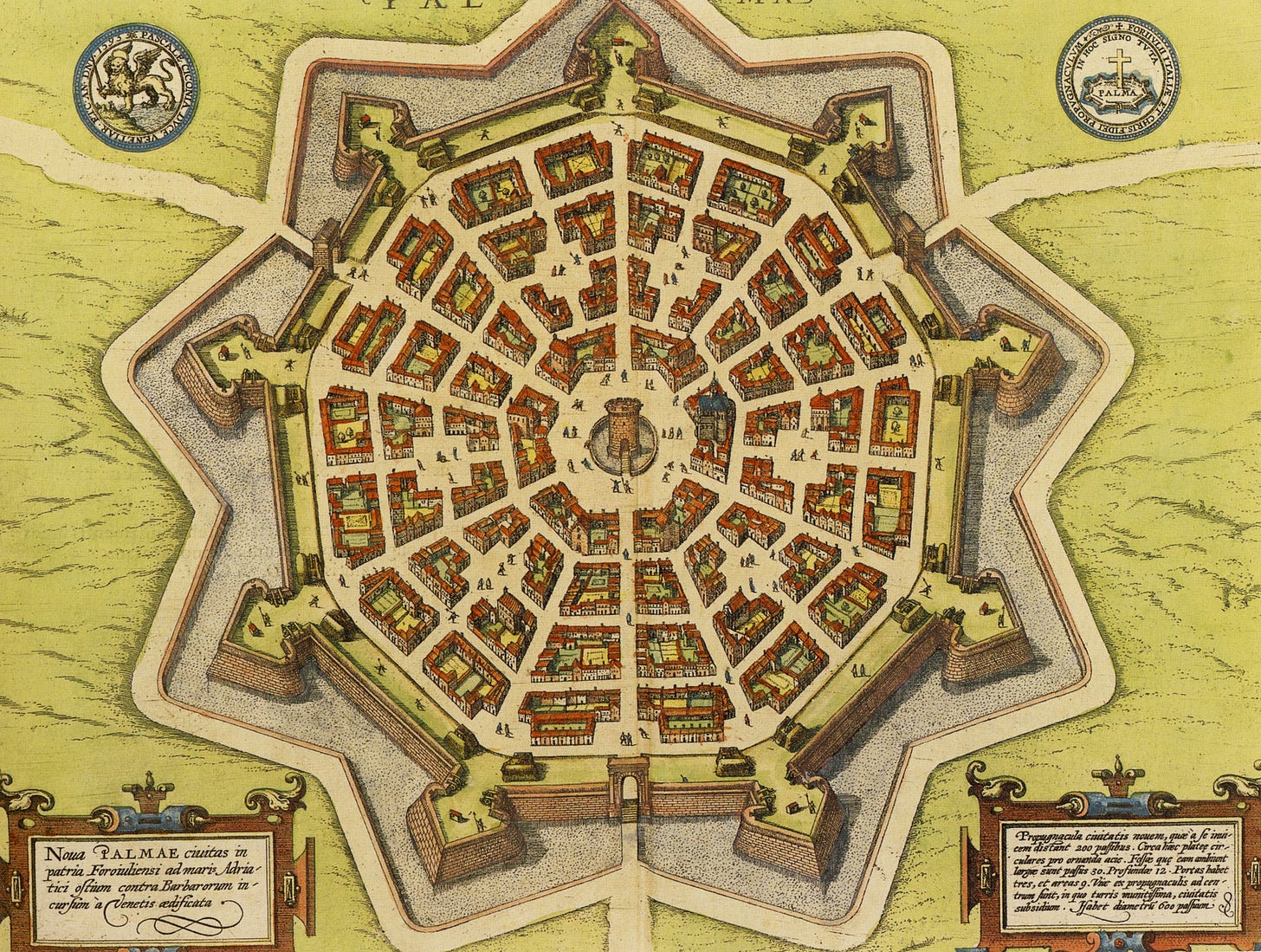

Parker's 'military revolution' was instead initiated by the emergence of the trace italienne fortress—a new design for city defense using thick (rather than high and vertical) walls, quadrilateral bastions, and large counter-batteries of cannon. Massive and massively expensive, the trace italienne was itself a response to developments in artillery during the fifteenth century, which rendered preceding fortifications obsolete and led vulnerable countries (Lombardy, the Low Countries, Hungary) to spend copious amounts on building new ones. States that could not afford the expense could be steamrollered by larger neighbors. Victorious polities, especially France, demolished as many interior fortresses as possible—partly as an economy measure, and partly as a centralizing measure to reduce the efficacy of future revolts.

The imperviousness of the 'miracle' works to artillery barrage and infantry assault handed the advantage in wars back to the defender. Campaigns were prolonged into chains of endless sieges, in which attackers required greater numbers of disciplined troops (to completely surround the walls and defend themselves against relieving armies) and defenders a panoply of guns. In 1639, half of the Spanish Army of Flanders and most of their Dutch opponent were sitting in garrisons. Battles became "irrelevant—and therefore unusual" as "[w]hoever controlled the towns controlled the countryside." None of the great victories of Gustavus Adolphus had proved decisive during the Thirty Years' War. Indeed, the sheer length of the Thirty Years' War was symptomatic of a shift in military strategy toward attrition, where supplies and morale gave out before the armies did.

Parker's paper created a paradigm in military history, linking military and social-economic factors in unprecedentedly convincing fashion. His arguments were famously influential for William McNeill, his editor at the Journal of Modern History, who incorporated military-revolution mechanisms throughout his survey The Pursuit of Power (1976). Nevertheless, the Parker paradigm, centered on the 1530-1700 revolution in fortress design, infantry organization, and state formation, was eventually challenged by military historians. Some pushed back on the details of Parker's claims; others presented entirely new paradigms.

In the following sections, I outline the major lines of attack against the ‘military revolution’ thesis.

Fortresses

John A. Lynn (1991) concurred with Parker's assertion that army growth drove state formation, but disagreed that the development of the trace italienne induced army growth. Defensive works had four goals: to 1) stop infantry from storming the fort 2) absorb bombardment 3) protect defenders 4) shell attackers. The 'bastioned trace' was, Lynn writes, essential only to (1); the real innovations were artillery, thick walls, and the surrounding ditches. Similarly, it was not the size of the fortress but the range of cannon that force attackers to build lines of circum- and contravallation so far around the fortresses. When the allies besieged Lille in 1708, their forces were only slightly larger than those that had stormed it in 1667—before Vauban had fortified it. Indeed, he marshals data suggesting that the size of besieging armies remained stable, at 20,000-40,000, from the fifteenth to the early eighteenth century.

One might argue that better fortresses increased the length of sieges and thus consumed larger armies, but on average individual sieges did not appear to have lasted longer or caused more casualties over time. Nor did the French commit to multiple simultaneous sieges; with few exceptions, both they and their enemies rarely fought more than one siege at a time across multiple theaters and almost never in one. Instead, Lynn argues that French economic and demographic expansion made larger armies possible and that Louis XIV's aggressive diplomacy (which forced France to fight multiple coalitions) made them necessary. Undoubtedly both were important factors, but it’s unclear to me that either surged rapidly enough to account to the growth the French army. Further, Lynn neglects Parker’s point about the importance of garrisoning (rather than just besieging) the fortresses.

Thomas Arnold (1995), studying the Duchies of Mantua and Montferrat, agreed with Parker that the trace italienne was an especially powerful fortification, but suggested that A) small states could afford them and B) they thus proved a hindrance to expansionist and centralizing royal governments. The fortification drive ensured the success of the Dutch and Huguenot revolts and prolonged German fragmentation. Yet Arnold's critique seems to substantially miss the point—conflating the construction of territorial empires with the creation of effective states. Fortresses helped to preserve the landward flank of the Dutch Republic—Europe's most efficient early modern fiscal-military power, if not a French-style absolutism.

Tactics

The most damaging direct critique of the 'military revolution' school, in my view, is David Parrott's “Strategy and tactics in the Thirty Years War: the ‘military revolution’” (1985). Parrott pours continuous volleys of fire onto the Roberts-Parker synthesis, asserting that A) no one actually used the ‘new tactics’ and B) they weren't effective anyway. First, he dismisses Maurice's reduction in unit size (from 1,500 to squadrons of 550 men, discussed above). While Parrott concedes that firearms made the initial fall from 3,000 to 1,500 inevitable, this second shift, he argued, was essential neither to the training (by increasing the officer/man ratio) nor the flexible deployment of armies. Adding more officers just increased expense, when so much of the actual training was carried out by veterans.

Seventeenth-century battles did not vindicate Maurician tactics. According to Parrott, the small-unit Saxon army nearly lost the battle of Breitenfeld for Gustavus Adolphus. The similarly-ordered German Protestant states, organized so due to a lack of veterans, suffered reverse after reverse until the Swedes' arrival. And Gustavus himself eventually abandoned the squadron, collating 3-4 into brigades. While effective unit sizes did continue to fall, this development was not welcomed—due more to disease and desertion than to intent.

Moreover, 'conservative' units were not closely-packed mobs of pikemen. Instead, six rows of pikemen—spaced liberally to permit mobility—presented arms to the enemy with 10 more in reserve; gunners started off to the sides, raced out in front the pike squares to fire, and then retreated backward through or sideways around the pikemen as the enemy closed. Pike squares, in the rare cases when they were deployed, had their purpose as a stable defensive formation. Parker and Roberts' preference for Maurician tactics, Parrott says, was ultimately founded on contemporary propaganda, not facts.

Finally, Roberts had asserted the importance of the Swedish salvo—the simultaneous discharges of several rows of artillery—in 'blowing holes' in enemy lines. But Parrott asserts that this wouldn't have worked: blasting away at opposing infantry would just pile up bodies in front of one's own advance, and most gaps could be plugged by the application of reserves. The potentially revolutionary change would have been the creation of a mobile horse artillery; but while Gustavus had produced a light three-pounder cannon that could be moved by a single horse in theory, they weren't actually moved in practice.

Parrott's broader point is simply that tactical changes were irrelevant by comparison with A) the increasing potency of infantry on the defensive and B) the size and experience of an army. A massive force could overwhelm a well-placed defense, while a novitiate force employing Maurician tactics would still be broken by a veteran command.2 The way to win a battle was not by complex infantry maneuvers, but by combining an intense infantry assault on the center with flanking raids by cavalry that could end up in the enemy rear.

Strategy

Parrott (1985) also criticized Roberts' suggestion of a 'revolution in strategy.' During the Thirty Years' War, he contends,"[t]he overriding need to pay and supply armies inflated beyond the capacities of their states, reduced strategy to a crude concern with territorial occupation or its denial to the enemy. Inadequate administration, or the limited Contribution-potential of the main campaign theatres sharply constrained the commanders' freedom of action" (242). With primitive logistics and desertion rampant, wastage rates of 50-57% were common for European armies.3 Consequently, commanders had only two options: A) to occupy territories that promised plunder or B) to remain close to centers of supply. Both constrained strategic decision-making.

Campaigns became about seizing regions with supply-potential and were divorced from political imperatives. After his decisive victory at Breitenfeld, for example, Gustavus chose to move slowly through the Rhineland imposing Contribution-system payments on its rich principalities rather than trying to end the war. This was in spite of the tensions the move created with the French. The practice of fielding multiple simultaneous armies, meanwhile, was likely due more to the impossibility of supplying the whole force in a single staging area.

Parker dissented. For example, he notes that in the fall of 1552, there were at least three simultaneous theaters involving the French: 1) a 6000-man garrison besieged at Metz by Charles V 2) a French field army sitting in Champagne, threatening Flanders 3) another army in Italy, first defending of Parma and then suppressing revolts in Siena. Large garrisons also occupied Savoy and the Pyrenees. Charles V was similarly engaged. King Henri II had arranged for the German Protestants and the Turkish Sultan to launch simultaneous attacks on the Habsburgs, who had to deploy armies and garrisons in Germany, Lorraine, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and North Africa—148,000 men in all. "[N]o state had ever maintained armed forces in so many different theatres at the same time before" (345).

Chronology

Clifford Rogers (1995) accepts the importance of the 'fortification revolution' emphasized by Parker and the 'administrative revolution' advanced by Roberts. But Rogers argues that there were two revolutions preceding 1560 that were equally important in shaping the 'western way of war': the "infantry revolution" of the Hundred Years' War and the "artillery revolution" of the subsequent century.

The High Middle Ages were, quite literally, the age of knights on horseback; many major battles were decided by charges of heavy cavalry. The man-at-arms was almost invulnerable—encased in armor, physically puissant thanks to a superior diet, and able to A) choose his time and place for battle and B) escape reverses. He was also costly to outfit (40 times that of an exceedingly well-armed bowman) and consequently the populous, rich, and feudal land of France had the most and best.

The supremacy of the knight forced France's rivals—England, the Flemish, and the Swiss—to find a solution. The English developed the six-foot longbow, which was 25 percent more powerful than opposing models for a given draw strength, and combined train bands of yeomen archers with dismounted men-at-arms. Recruiting from the commoners (rather than just the aristocracy) significantly increased the cost-effectiveness of the fighting man and the size of armies. At Courtrai in 1302, the county of Flanders alone mustered an army greater than the French force of men-at-arms and won a decisive victory. With the disposable commoner doing more of the fighting, and with the importance of holding tight pike formations, the taking and ransoming of prisoners waned and battles became bloodier.

After the Infantry Revolution came the Artillery Revolution. Gunpowder artillery was initially small (but cheap), and in siegecraft was primarily used to shell the town (rather than penetrate the walls). Consequently, a fortress could last for over six months even against a force with dozens of guns (albeit at some cost). But innovations in artillery technology shifted the balance between attack and defense. First, barrel length was more than doubled, increasing the accuracy, muzzle velocity, and range of the shot. Second, the long guns began to be manufactured by fastening together iron staves with bands of white-hot iron (like the hoops of a barrel) while the addition of limestone made iron (and thus guns) cheaper. Stronger guns were compatible with engrained powder—which augmented the charge's explosive force—which replaced the traditional "sifted" version over 1400-30. Soon, the great powers were spending colossal amounts on artillery trains, which were proving adept at leveling medieval castles. Fortresses that had taken months to starve out now fell in weeks or even days. To this development Rogers attributes the formation of Spain and France—the former reducing Granada in 'only' ten years; the latter snapping up Aquitaine, Normandy, Burgundy, and Brittany.

Jeremy Black (1991) goes further, arguing that "the 'revolutionary' periods were c. 1470-c. 1530, c. 1660-c. 1720 and (primarily because of the levée on masse rather than tactics) 1792-1815. Roberts' emphasis on 1560-1660 is incorrect" Parker, Roberts, and Rogers had failed to recognize the consequences of innovations after 1660. On land, the 1660-1720 period saw the replacement of the pike by the socket bayonet (which allowed a gun to discharge with bayonet fixed) and the matchlock by the flintlock, as well as the introduction of the pre-packaged cartridge. The real increases in standing armies, meanwhile, occurred after the Roberts period.

Though Rogers and Black contest the chronology of the 'military revolution', neither really challenges the paradigm. Warfare and state-building interact in a positive feedback loop:

[C]entral governments of large states could afford artillery trains and large armies. The artillery trains counteracted centrifugal forces and enabled the central governments to increase their control over outlying areas of their realms, or to expand at the expense of their weaker neighbors. This increased their tax revenues, enabling them to support bigger artillery trains and armies, enabling them to increase their centralization of control and their tax revenues still further, and so on.

Whether technology and tactics evolve through punctuated equilibria or in centuries-long 'revolutions' (the difference is imprecise), the challenges of inter-state military competition remain pivotal for the expansion of tax-raising bureaucracies.

Technology

Bert Hall and Kelly DeVries (1990), in a critical review of Parker's book, emphasize his careless descriptions of technological evolution. First, they dismiss his claim that Spanish muskets could penetrate plate armor at a range of 100 meters. Even in the 16th century, they argue, the armor and speed of cavalry allowed them to charge and scatter infantry while reloading; pikes were necessary to protect musketeers, and remained so until (as Black noted) the invention of the bayonet. Second, Hall and DeVries argue that Parker confused volley fire with the countermarch in order to inflate the importance of the Dutch reforms. More fundamentally, they accuse Parker of technological determinism—reviving a 'Whiggish' narrative in which gunpowder "blasts away" the feudal order.

In a 1998 paper, the authors contested the arguments of the expensive artillery train for state formation—that only central treasuries (rather than nobles) could afford cannon, and that only centralized monarchies could afford a significant number of them. France and Burgundy conformed to this pattern, monopolizing the use of gunpowder weapons and deploying them for the reduction of local power. The English Crown had a monopoly on gunpowder weapons, but refused to use it against domestic actors and eventually lost it during the Wars of the Roses. Hall and DeVries interpret these differences as demonstrating the predominance of political considerations over technologically-determined decision-making.

Other authors have criticized the models of technological diffusion implicit in the military revolution thesis. J. C. Sharman, for example, approvingly quotes Jeremy Black, Wayne Lee, and Jon Elster in disparaging the ‘learning’ framework employed in Hoffman’s Why Europe Conquered the World (2016). Black wrote that military historians of a Parkerian cast subscribe to “a somewhat crude belief that societies adapt in order to optimize their military capability and peformance” and a “some mechanistic, if not automatic, search for efficiency.” Lee likens this ‘rational choice’ reasoning to ‘challenge-and-response’ theories of technical change: “The implicit dynamic . . . is one of direct conscious response: historical actors determined the need for a new system or a new technology and therefore developed one.” Elster and Sharman rejoin that a Clauswitzian ‘fog of war’ prevents historical actors from identifying superior technologies or even the causes of victory with any degree of certainty.

Similarly, Sharman and Lee accuse ‘military revolution’ scholars of subscribing to an unreconstructed Darwinian-selection-based view of technical change. In essence, states are supposed either to adapt military innovations or face conquest by neighbors—in both ways driving out inefficient forms of military organization. They suggest that the ‘Darwinian’ requires three assumptions: “the ‘death rate’ amongst organizations has to be very high, the differences in effectiveness have to be large and consistent, and the environment has to stay fairly constant” (Sharman 2019, p. 22). None of the three, they claim, was true of early modern Europe. States were durable; battles were rarely decisive and were influenced by multiple factors; and some innovations weren’t universally useful across environments. This isn’t precisely a straw man, but it’s an accurate characterization of neither Parker nor Hoffman. The latter centers “glory,” not “extinction risk,” as the primary motivation for rulers to improve militarily; Parker, meanwhile, recognizes causes of warfare ranging from the religious to the political-dynastic. It is doubtful that either Parker or Hoffman would deny the importance of the ‘cultural’ factors—ranging from religion to political economy!—emphasized by Sharman. Indeed, one of Parker’s contributions was to devalue the decisive battle and center the contribution of finance and logistics to victory in attritional wars. Thus Sharman’s critique misses the mark here.4

Army Size and State Formation

The pressures of war-making obviously did not immediately crystallize in Weberian bureaucracies. Parrott and others point out that the classic 'military revolution' phase was the age of the military entrepreneur—the roving merchant of death who raised and hired out bands of mercenaries to fill out the ranks of absolutist powers. It was men like Wallenstein who raised forces on their personal capital and credit facilities, not the war departments of the absolutist states. The Thirty Years' War was fought by mercenary, not national, armies wielded by pre-tax fiscal states. These facts are taken to imply a weak correlation between army recruitment and state mobilization.

This argument misses the point. In the military revolution model, the fiscal pressures generated by the expansion of army sizes induces the creation of the bureaucratic tax state. Parrott's own case study, France, is instructive here. Colin Jones describes how the French army was initially recruited by decentralized and corrupt officials. Colonels were responsible for raising regiments through voluntary enlistment, selling captaincies to high bidders who then went around collecting men—some seigneurial lords rounding up their peasants, and other men raiding hospitals and prisons. These 'military contractors' were also charged with disbursing payments (which they reduced for their own profit), providing clothes and arms, and giving medical care to their troops. Faced with this perverse incentive, the commanders skimped on their responsibilities and flagrantly overcharged for what they did provide. Starvation and disease were rampant in the camps, from which desertion was equally common.

What held this motley crew together was not patriotism, but plunder—the opportunity to loot on campaign and thus replace what income the financially-inept French state would provide. Richelieu encouraged plunder as an incentive for better performance. Towns could be nailed again under the 'Contribution System', pioneered by Portuguese pirates in the Indian Ocean, which allowed towns to pay cash in exchange for exemption from plunder. Beyond open loot and heavy taxes, citizens—in lieu of centralized barracks—were also forced to billet soldiers in their homes and provide them with food and bedding.

The increasing costs of raising large armies without adequate logistical systems induced state formation. As armies grew, they required larger foraging areas—effectively an invitation for foraging parties to desert. Desertion prevented the training essential to the function of a modern combat infantry and thus had to be stopped. The only remedy was improving systems of centralized taxation and supply.5

Centralization remained imperfect and incomplete. Taxes were farmed out or collected by men who bought their offices, and thus Intendants had to be appointed to supervise revenue officials. They also aided in the recruitment of the regular army and militia and helped to reorganize France's parlous logistics. By creating non-venal posts in the high command, Richelieu and the heads of the War Department gradually subordinated the officer class and introduced promotion by merit. Weapons production was standardized and centralized in state arms factories; magazines were established to supply the troops on home soil; French officers took responsibility for raising foreign troops; and in 1763 recruitment was made a royal monopoly.

A similar process took place in England. Absent in the Hundred Years' War, the English army remained small until the Nine Years' War (1689-97), though key shifts in sixteenth-century fiscal policy—the 'Tudor Revolution in Government'—were in large part efforts to fund military spending. After 1585, foreign military expeditions increasingly required to Parliamentary taxation (Braddick 2000). But fiscal innovations began in earnest during the English Civil War, when Parliament created the excise administration—collecting taxes on the production of a wide range of goods—to fund a standing army which reached 70,000 men under the Commonwealth. The demands of the navy were similarly exigent; the fleet added 217 vessels from 1646 to 1659 and 25 battleships were started after the Restoration amid wars with the Dutch for commercial pre-eminence in the North Sea.

Retrenchment ensued during the Restoration, but the advent of the 'Second Hundred Years' War' after the Glorious Revolution forced the English to centralize and expand their tax bureaucracy. As John Brewer notes, average annual tax revenues were £3.64 million during the Nine Years' War, roughly double the state’s tax income before the Glorious Revolution. Forty years later, during the War of Austrian Succession, annual revenue exceeded £6.4 million, and £12.0 million by the American Revolution. By the late eighteenth century, the British were likely the most-taxed people in the world, in possession of a colossal public debt—but also an effective navy, a passable army, and an efficient fiscal apparatus.

While fortifications and armies were expensive, I would argue that a broader definition of the military revolution—embracing the influence of military competition on the quality and scale of European war machines—simply fits the evidence better.

The Fiscal-Military State

The rise of the 'fiscal-military state' in Europe—implying a symbiotic relationship between militarization and state formation—is one of the better-established points in early modern economic history. This literature is in part derivative of two pathbreaking works: John Brewer's The Sinews of Power (1988), which analyzed the rise of the fiscal state in Britain, and Charles Tilly's Coercion, Capital, and European States, 990–1992 (1992).6 Brewer's 'sinews' are state finances, and his work is a case study that lays out the origins of the British fiscal-military state along the lines described above—the extension and rationalization of the excise and customs administrations in response to the intense fiscal pressures of war with France.

It is to Tilly, meanwhile, that we owe the dictum: "war made the state, and the state made war."7 More specifically, he writes that "War and preparation for war involved rulers in extracting the means of war from others who held the essential resources - men, arms, supplies, or money to buy them... extraction and struggle over the means of war created the central organizational structures of states" (Tilly 1992, p. 15). Modes of state formation differed between 'capital-intensive' regions with plentiful cities and markets, and 'coercion-intensive' regions with large agrarian hinterlands and little commercial development. In the end, the exigencies of large-scale interstate conflict led to convergence on the 'national state,' combining sizable rural populations, capitalists, and market activity. This hybrid had the men to field a standing army and the funds to pay it. Competition produced bigger states and costlier wars, which in turn demanded ever-greater investments in long-term taxation and borrowing capacity.

Surveys and case-study evidence abound in the works of Bonney (1999), Glete (2002), and Storrs (2012). While national development paths varied, military pressure clearly produced incentives for improving systems of taxation and public finance. Storrs concludes that "all are agreed that the European way of war and the military establishments which the various states maintained were very different in 1700 from what they had been in 1500. Armies were much larger, more complex in composition and structure, and more permanent; they were also much more expensive, not least because they required a whole range of services - arms, provisions and other supplies" (3).

Dincecco (2012, 2015, 2016, 2018) has written extensively on the interaction between war and the rise of the fiscal state. He credits the fragmentation of Europe with 'externalizing' conflict and created 'multidirectional' threats, which in turn forced rulers to call Parliaments to negotiate with elites for revenue. Further, the threat of conflict drives urbanization through a 'safe harbor' effect; this leads in turn to the development of urban institutions, the protection of property rights, the accretion of human capital, and innovation.8

The workhorse model of European state capacity, Besley and Persson (2009), similarly centers warfare. Their argument, citing Tilly, posits that war-making is a public good and thus that increased demand for its provision leads to an increase in state capacity. Gennaioli and Voth (2015), in another heavily-cited paper, qualify the Besley-Persson perspective, suggesting that the development of fiscal capacity depends on whether success in conflict is contingent (or at least perceived as contingent) on the attainment of increased revenue.

None of this is to say that the 'fiscal-military state' model is unimpeachable or unchallenged. But the major lines of criticism—that states did more than just spend on war, and that non-Weberian forms of recruitment and revenue generation augmented bureaucracy—do not really undermine the fundamental point: that European states, whether via coercion or compromise, found the pressures of inter-state conflict the most compelling demand for increasing their tax-raising capacity.

Conclusion

It's important not to exaggerate the significance of early modern technological change. Just as economic growth rates prior to the Industrial Revolution were low compared to those of the last two centuries, so too the rate of innovation in military technology and organization of 1400-1750 paled before that of 1815-1989. Nevertheless, significant improvements (if they may be so termed) in the art of killing did take place. A modest force of French musketeers in 1750 would have wiped the floor with the flower of French knighthood from four centuries before; Wellington’s Coldstream Guards would have made short work of Elizabethan bowmen; and Nelson's Trafalgar-vintage squadron would have torn apart the combined might of the English and Spanish armadas of 1588.

This increase in firepower was not merely a technological phenomenon. Weapons improved, of course, but so did training, organization, supply, and infrastructure—altering the nature of warfare forever. The causes of this revolution in military capability9 were multifarious, ranging from geography to intellect not excepting plain luck. But it seems absurd to suggest that, in this pre-scientific age, the greatest force advancing the war-making ability of states was anything other than war itself. Whether inter-state conflict was a 'Darwinian struggle' (as critics like Sharman can seem to caricature the MR hypothesis) or a tournament of rulers (as Hoffman contends),10 the incentives to improve at fighting were powerful. Larger, better-financed states absorbed smaller, weaker ones; small states that did pursue successful strategies of finance and organization (e.g. the Dutch Republic) persisted and adapted. Surviving losers—and other interested parties—copied perceived winners.

I'm not arguing that ideology and politics were irrelevant. As multiplayer games of EU4 so aptly demonstrate, national motivations for conflict were bizarre, convoluted, and often irrational. Hoffman's model has rulers chiefly pursuing 'glory,' taking Louis XIV as an exemplar. The terms of 'survival' for the Habsburg or Bourbon dynasties might be defined differently for Tudor England and the Dutch Republic, let alone the minor Italian states. Religious, dynastic, and commercial disputes might be cast as life-or-death struggles by interested parties when the risk of state annihilation was low. But whether European states wanted or needed to fight, they had to prepare for it all the same—the more men and money thrown at the problem the better.

Nevertheless, it's not clear that we can pick out any century as one of exceptionally rapid change in technology, tactics, and organization. Roberts was incorrect in giving priority to the performances of the Swedish army in the Thirty Years' War, but Black was equally errant in dismissing Roberts' century and asserting the importance of the two bracketing it. I find Rogers's formulation, in which technology evolves slowly through 'punctuated equilibria' over several centuries, to be a bit more compelling. I might go further: to eschew any particular model beyond the state-system's competition mechanism.

Of course, there’s a great deal of ambiguity in that framework. Is there an optimal number and size of competing states for promoting military innovation? A panoply of tiny states might be highly competitive; on the other hand, micro-states might lack the capital to invest in new technologies and sufficient manpower to execute mass warfare. Larger proto-national states were abundantly supplied with (at least the potential to amass) both, but a few major players in the state system fundamentally changes competition dynamics: spheres of interest, tacit limits on conflict severity, and dynastic unions can all diminish the ‘necessity’ of innovation.11 Some states might just be too large to swallow, whether because of the logistical challenges of the initial conquest or the impossibility of long-term military occupation and territorial absorption. The competition model is also conditional on a range of underlying economic, cultural, and political factors: the existing productive/population bases of participants, religious dispositions to conquest and conversion, and the ability to forge alliances. For the Dutch Republic and Britain, the creation of an efficient fiscal-military state was never going to end in the re-establishment of Burgundy or the Angevin Empire—in one sense, survival and independence from French geopolitical. influence were victories in themselves. Those outcomes were also to some extent dependent on geographical impediments on invasion routes. The contest between population and technology/efficiency and the mediation of geography will be central to succeeding posts on the global effects of the military revolution.

This definitely is not a comprehensive review—I have necessarily omitted the majority of the vast historical sociology, IR, and economic history literature on bellicist theories of state formation. Here, I focus more narrowly on the debate on the ‘military revolution’ thesis as defined by Roberts and Parker.

“In the last resort, the Spanish, Imperial and Swedish armies won battles, not because of their tactical practices or innovations, but because they perceived themselves as elite forces, embodying a national military reputation for which they were prepared to make a far greater personal commitment and sacrifice than their opponents.”

Richelieu noted that telling a unit that it would soon be moving into Germany would reduce it by 50 percent overnight.

I’ll have more to say about Sharman in subsequent parts.

There were also political and ideological motives. Mercantilists of the day, convinced that production was the basis of state power, were aghast at the thought that militaries looted their own producers. And Louis XIV's regime had an inherent bias toward centralization, which augmented his revenues and domestic authority—and in the military sphere, allowed him to extract the rents which had previously gone to military entrepreneurs under the Contribution System.

Connections between state-building and military spending were not new at the time (see Bean, Moore, Mann, and many, many others), but Brewer and Tilly helped put the 'bellicist' theory in the historiographical limelight. For what it’s worth, those are also the two books that economic historians have read…

Rosenthal and Wong (2011) similarly suggest that city walls protected urban industry and that high-wage environment led to directed technical change.

A 'military revolution', if you will…

Neither of which are wholly true.

I’m actually a Mokyr partisan on this issue and agree that necessity is not the mother of invention in general, but if states A) invested in warfare B) fought a lot or watched others do so and C) were open to improvement it seems unlikely that innovation should not be more rapid than when neither A, B, nor C is fulfilled.

Sharman’s book on Company States is much better and more interesting than his MR book. He is also quite a mediocre and repetitive writer.

Also, I find it weird and disappointing how little theories of Military Revolution interact with the growing dominance of early-modern navies. Navies were one area where Europeans achieved unambiguous global domination and vital to military conflicts of the period. They also played a much larger role in colonialism than pike-and-shotte formations

I realize you already have a lot on your plate, but I'd love to see a discussion of the relationship between the (mostly European) "military revolution" debates and the (mostly not European) "gunpowder empire" literature.