Jared Diamond: A Reply to His Critics

Rescuing Guns, Germs, and Steel from its worst detractors

Many academics cherish an irritating myth: that Jared Diamond's Guns, Germs, and Steel is an error-strewn and racist endorsement of European imperialism. One mention of Diamond's name is enough to get everyone in earshot to regurgitate their favorite streams of invective against his books. A 2013 article in Capitalism Nature Socialism by David Correa, entitled "F ** k Jared Diamond," decries the aging geographer as a "racist", a "hack", and the "darling of bourgeois intellectuals"—and that’s just on the first page. Others lambast Diamond for using "geographical determinism" to excuse Europeans for the bloody consequences of the conquest of the Americas.

There are three ultimate factors behind the emotional reaction to Diamond’s work. First, academic cancel culture frowns on attempts to attribute cross-country economic outcomes to intrinsic factors—anything that might make rich Europeans appear superior to the rest. But Guns, Germs, and Steel—which is explicitly anti-racist—does the opposite. It tries to explain "why history unfold[ed] differently on different continents" with answers that don't "involve human racial differences" (9). Geography is just dumb luck.1 Diamond doesn’t believe in any innate European ‘superiority’: the opening passages of the book actually suggest that New Guineans might be smarter than Western readers! Second, academics—myself included—tend to vilify “outsiders” who cross disciplinary boundaries without understanding our local scholarship norms. Finally, there’s just some plain envy. Diamond has written an ambitious and popular book, something that many fields don’t manage in decades.

But emotion, while understandable, doesn’t lead to good scholarship. And while Guns, Germs, and Steel (henceforth GGS) isn’t perfect—there are perfectly reasonable issues one can take with every chapter—it’s not wrong in some of the ways that its legions of critics seem to think. I am not making a full-throated defense of the book’s factual accuracy, and indeed, as a 26-year-old work of popular science, I’d be shocked if specialists hadn’t revealed inaccuracies in the intervening years. But GGS’s detractors are often mistaken about why the book is flawed. In this essay, I will deal with four kinds of common but errant critiques:

Diamond is a geographical determinist: that is, he writes a monocausal history of the world in which A) the environment is the only factor and B) human beings have no agency.

Diamond absolves Europeans of blame for the crimes of imperialism through his geographical determinism, since the conquerors couldn’t help but seize the helpless Americas.

Diamond excuses Europeans for the destruction of New World populations by overemphasizing disease (rather than colonialism) as the chief killing agent.

Diamond is a Eurocentrist, vaunting the West above the backward Rest and suggesting that the Great Divergence was inevitable. Europe’s technological advantages were limited.

Europe’s geography did not make fragmentation into a competitive state system more likely.

Given the bad press that Diamond’s received over the years, you might be surprised to learn that each line of criticism is (almost embarrassingly) wrong. Here’s why.

Diamond is no more a geographical determinist than the “approved” authors on the Great Divergence and the Columbian Exchange, from Alfred Crosby to Ken Pomeranz. Furthermore, his thesis is neither monocausal nor deterministic. His other works clearly emphasize the role of human agency in history.

Diamond isn’t a geographical determinist in the first place (see above) and suggests that cultural factors stoked Europeans’ crusading zeal. Either way, positing an explanation for why Europeans were able to conquer the Americas does not excuse them for doing so, and with such brutality.

Diamond’s critics conflate the role of virgin-soil epidemics in the conquest with their role in the decline of Indigenous populations. Diamond is mostly interested in the former, so the fact that VSEs may not completely explain the New World demographic catastrophe does not invalidate his argument concerning disease’s centrality to Iberian imperial success.

Diamond self-evidently is not a Eurocentrist—GGS focuses on the rise of Eurasia—and is skeptical about the merits of Western civilization. But military histories of the conquest support the assertion that the small parties of Spanish soldiers were able to defeat much larger Native armies thanks primarily to their superior steel weapons and organizational capacity, in line with Diamond’s argument.

Recent economic history research suggests that Europe’s geography (mountains, lakes, bays, and discrete agricultural cores) made fragmentation likely, if not inevitable.

I’ll briefly summarize the book (GGS) and then dismantle each of the above four-and-a-half arguments in detail.

Guns, Germs, and Steel: An Executive Summary

I want to pause and outline Diamond's thesis, because I’m convinced that simply understanding the argument should dispel all of the above claims. Diamond attempts to answer "Yali's question", the crown jewel of the social sciences: what explains the enormous international inequalities in technology, wealth, and power that persist in today's world? In 2020, to illustrate, GDP per capita was $59,920 in the US, $14,064 in Brazil, and just $936 in the Central African Republic. The official languages of these countries are English, Portuguese, and French—the languages of their colonial conquerors. The official currency of the CAR is the CFA franc, imposed on French colonies in 1945, pegged to the euro, and still said to impede economic development.

Diamond's explanation is deceptively simple, and it's probably this that got him into trouble in the first place.2 Out of the sites in which agriculture was independently invented—New Guinea, China, the Middle East, North America, Mesoamerica, and the Andes (and more recently, appending North/East Africa and India to the list)—Mesopotamia had the easiest to tame, fastest-growing, and largest-seeded plants. Eurasia in general also had a bunch of large animals, like horses, donkeys, aurochs, sheep, and goats, that could be domesticated for productivity increases. Diamond counted 13 species of domesticable animals over 100 pounds in Eurasia, one in South America, and none whatsoever in the rest of the world. Human hunters killed off the potential candidates in North America and Australasia during the Pleistocene, and the remaining African species, like zebras, onagers, and the African elephant, either proved untameable or difficult to breed in captivity.

Eurasia's east-west supercontinental orientation facilitated the relatively rapid diffusion of "technologies" to its poles, whereas traversing vertically-oriented3 continents like Africa and the Americas required innovations to pass through new ecological zones at different latitudes (rainforests, deserts, pampas, etc.). Further, these continents contained chokepoints (i.e. the isthmus of Panama) and outright "ecological barriers" in which agriculture was unsuitable. "As a result," writes Diamond, "there was no diffusion of domestic animals, writing, or political entities, and limited or slow diffusion of crops and technology, between the New World centers of Mesoamerica, the eastern United States, and the Andes and Amazonia" (366). Similar story in Africa. But in Eurasia, Mesopotamian plants, animals, and agricultural techniques reached the Mediterranean by the first millennium BC and Europe by the first millennium AD.

Concentrations of domesticable plants and animals permitted the accumulation of food surpluses, which in turn allowed societies to support members working outside agriculture. This meant craftsmen and scribes, whose labors accelerated technological progress, as well as priests, kings, and bureaucrats, who created hierarchies and states. Food surpluses also permitted more dense settlements, with the result that Eurasia received the bulk of the world's population and the majority of the inventions. Combine high population density, proximity to animals, and long-range trade networks, and one also gets the devastatingly toxic Eurasian disease pool—smallpox, influenza, measles, etc. Eurasians developed immunity to many pathogens, but the Americas, excluded from the periodically devastating plagues, did not. Thus guns, germs, (writing,) (states,) and steel.

Thus Diamond argues that the early European colonists of the Americas hit unprepared native societies like a whirlwind. Deadly plagues ripped ahead of the conquistadors, who then toppled the already-weakened American polities via brutal conquest and massacre, aided by local allies. Africa was harder to seize, in part thanks to its links with the Eurasian disease pool via southern Asia. But the "technological and political differences of A.D. 1500 were the immediate cause of the modern world's inequalities. Empires with steel weapons were able to conquer or exterminate tribes with weapons of stone and wood."

Diamond also attempts to explain why European, rather than Chinese, conquerors were the ones who did all the colonizing. This is a simple balkanization theory—Europe divided into many areas conducive to states, China formed a great homogenous core—that does not need lengthy restatement. Europe has a highly indented coastline with multiple large peninsulas, all of which developed independent languages, ethnic groups, and governments, plus two large islands. The Chinese heartland, meanwhile, is connected by two large river valleys—the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers—from east to west, and bound from north to south by relatively easy transit between those two tributaries. Europe, consequently, boasts many independent core regions that have been impossible to unify, even under the Romans; China has only been politically fragmented for (relatively) brief spells since 221 B.C. Consequently, Europe received the benefits of interstate competition for power (rise of the fiscal-military state), entrepreneurs, and inventors; China's rule by single autocrats left it vulnerable to lock-in on bad decision paths.

If you're wondering what infuriates Diamond's critics, you're not alone. Not only are some of his ideas standard fare in the social sciences, as well as familiar tropes in popular culture, but many of them also aren't originally his. Indeed, we'll see that Diamond's thesis draws heavily upon—and is no more execrable than—the writings of the historian Alfred Crosby, whose name has escaped similar disrepute.

Geographical Determinism

What is a geographical determinist? It's one of the criticisms most often leveled at Diamond, so we should know what the term means. On the one hand, you might say that it's the belief that "all of the important differences between human societies, all of the differences that led some societies to prosper and progress and others to fail, are due to the nature of each society's local environment and to its geographical location"—the view James Blaut ascribes to Diamond. Man is helpless in the face of the world's physical and ecological features, the true blind watchmakers that set history running. On the other hand, though, you could be deemed a geographical determinist because you think that environmental factors are the uncaused variables in your model of historical change—that is, that they are exogenous. In this sense, most economic historians are geographical determinists. There's very little a person or a country can do about the size of their continent. But they can adapt in the face of their constraints. Exogenous causes can have small effects.

Diamond would absolutely repudiate the first, stronger position:

But mention of these environmental differences invites among historians the label 'geographic determinism,' which raises hackles. The label seems to have unpleasant connotations, such as that human creativity counts for nothing, or that we humans are passive robots helplessly programmed by climate, fauna, and flora. Of course these fears are misplaced. Without human inventiveness, all of us today would still be cutting our meat with stone tools and eating it raw, like our ancestors of a million years ago. (408).

As he writes in the Introduction, "geography obviously has some effect on history; the open question concerns how much effect, and whether geography can account for history's broad pattern" (26). On the spectrum between "geography has no effect" and "geography has a big effect," Diamond's obviously closer to the latter—that's the whole point of the book. But he explicitly leaves open channels for other factors, from culture and institutions to contingency and plain luck. Diamond himself writes that "[o]ther factors relevant to answering Yali's question, cultural factors and influences of individual people loom large" (417). Consider the end of the great Chinese treasure voyages of 1405-33. It was not geography that stopped them from happening, but rather the outcome of a political struggle that became path-dependent because of China's unification. A different choice might have locked in another outcome. Indeed, geography in this case accentuated the salience of individual choice and political conflict.

As regards culture, Diamond suggests that environmental factors may have played a minor role in the manifestation of the Indian caste system, Confucian philosophy and cultural conservatism in China, and the distinctive colonizing tendencies of Christianity and Islam. Together, these forces—at least in the accounts of many traditional comparative historians—shaped much of early modern history. That's some concession, barely watered down by Diamond's insistence that geographical factors be taken into account first.

The actions of individual people matter, too. Had the Stauffenberg plot succeeded, for example, the Cold War (per Diamond) might have played out differently, resulting in an alternative postwar map of Eastern Europe. In explaining history's broadest long-term patterns, however, individuals have little influence—"[p]erhaps Alexander the Great did nudge the course of western Eurasia's already literate, food-producing, iron-equipped states, but he had nothing to do with the fact that western Eurasia already supported literate, food-producing, iron-equipped states at a time when Australia still supported only non-literate hunter-gatherer tribes lacking metal tools” (42).

Moreover, Diamond explicitly eschews a deterministic, physics-envying approach to a "science of history." Scientia, he reminds us, means knowledge, and each discipline has its own special means of attaining it. However, his description of the means available to historians probably helps to get him into trouble. History, he claims, has four dissimilarities to the hard sciences: methodology, causation, prediction, and complexity. That doesn’t mean that historians are forbidden from producing systematic knowledge about the past. Scientists can do experiments, while historians can't—but they can exploit ‘natural experiments’, leveraging variation in a treatment between cases to assess its effects. Second, historians (per Diamond) can and should aspire to uncover the ultimate causes underlying why events obtain.

As a non-historian, however, Diamond was probably less conscious of the trend in the discipline away from the kind of research that he advocates. While economic historians have adopted natural experiments and the estimation of causal effects as a paradigm, many standard historians have become wary of even loosely asserting causation (though they no doubt do so implicitly). Indeed, some believe that the implication that X causes Y asserts a deterministic relationship between the two variables—that if X is some geographical or environmental factor in a country, then outcome Y will always obtain, regardless of human agency. Of course, this isn't true. The social scientific definition of a causal effect is basically the counterfactual change in the strength of the effect if the cause were to be removed. When Diamond talks about geographical causes, he means geographical influences on populations over time, shaping human incentives. Causation isn't determinism.

Diamond rightly complains about this in an essay (published on his website) entitled "Geographic Determinism":

Today, no scholar would be silly enough to deny that culture, history, and individual choices play a big role in many human phenomena. Scholars don’t react to cultural, historical, and individual-agent explanations by denouncing 'cultural determinism,' 'historical determinism,' or 'individual determinism,' and then thinking no further. But many scholars do react to any explanation invoking some geographic role, by denouncing 'geographic determinism' and then thinking no further, on the assumption that all their listeners and readers agree that geographic explanations play no role and should be dismissed.

His assertion that geography is one of the many factors influencing historical processes, and that in some cases it has overwhelming and in others minimal causal effect, is perfectly anodyne. In fact, it's often the critics who adopt monocausal explanations; for example, James Blaut defines "environmentalism" as the "practice of falsely claiming that the natural experiment explains some fact of human life when the real causes, the important causes, are cultural" (Blaut 2000, p. 149). If only he could see the irony.

If you still believe that Diamond is a “geographical determinist”, it may be helpful to meet a real one. Take the Stanford archaeologist Ian Morris, for example, whose most recent book is literally entitled Geography is Destiny. Morris endeavors to show how Britain's island status interacted with the state of technology to determine its role in the world—rising from backwater in antiquity to commercial powerhouse in the age of mercantilism. His magnum opus, Why the West Rules—For Now, is predicated on the principle since that human biology and sociology are basically the same across world regions, the main differences between societies result from geographical factors. People respond just about uniformly to their material—geographical, economic, and technological—constraints. The rise of Europe is attributed to its isolation at the frigid tip of Eurasia, which encouraged the proliferation of maritime technologies and a mechanistic worldview, both crucial to turning English coalfields into industrial dynamism. Geography promoted institutions—banks, limited government, representation—suitable for growth and boosted the returns through access to foreign trade and colonies. Culture, meanwhile, is discounted entirely:

Culture is less a voice in our heads telling us what to do than a town hall where we argue about our options. Each age gets the thought it needs, dictated by the kind of problems that geography and social development force on it… This would explain why the histories of Eastern and Western thought have been broadly similar across the last five thousand years… because there was only one path by which social development could keep rising.

Diamond, as we've seen, argued that culture is an important aspect underlying economic development—and even that culture, in the form of Christian imperialism, propelled Europe to conquer the Americas.4 Morris, meanwhile, even adds that China's lack of coal reserves doomed it to agrarian stasis in the absence of Western development and 'computes' a half-baked index of civilizational development—something Diamond was much too circumspect to do.

In any event, GGS is no more deterministic than the works of Alfred Crosby, the still-venerated (if now obscure) historian whose research clearly informed Diamond’s own. Across two famous texts, The Columbian Exchange (1972) and Ecological Imperialism (1986), Crosby tried to convince environmental historians to view nature as an agent and cause of historical change, not just a passive recipient of human action. Crosby wanted to understand the rise of neo-Europes in the world's temperate zones, colonized both by white European settlers and by European flora and fauna. Moreover, the neo-Europes—places like America, Argentina, Uruguay, and New Zealand—exported vast quantities of foodstuffs, including $13 billion of the world's $18 billion in wheat. European settlement was driven by land shortage, nation-state rivalry, and religious persecution, and enabled by improvements in transportation technology. But why were certain regions so amenable to European settlement, despite military efforts by the colonized to resist it?

His explanations for Europe's imperial triumphs are, of course, ecological—and unsurprisingly reminiscent of Diamond's. Millions of years ago, the "seams of Pangaea" opened, splitting the great supercontinent into the blocks that eventually became Eurasia, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. Now and then, land bridges connected the continents, but for the most part, each played host to independent biological development. The biotas of the neo-Europes, however, were "simpler" (having fewer species) than those of Europe, which was linked to the vast geographical complex of Asia (many of the original inhabitants being drowned, as Diamond would later suggest, by the tide of early indigenous settlement). Since humans were alien to the Americas and Australasia at the time of their arrival, there were few parasites in existence that had adapted to prey upon them. Consequently, no major human diseases (to Crosby's knowledge) had originated in Australasia and few in North America, besides the uncertain case of syphilis. Their populations—like any invasive species—grew rapidly, and they were able to quickly adapt their hunting techniques to wipe out unprepared native megafauna, from the mammoth to the moa.

The destruction of native biodiversity in the later-settled regions meant that they were more susceptible to the introduction of new species when the first European settlers arrived. On the South African veldt, where many large species of browsers and carnivores survived, the early Dutch migrants struggled to increase their livestock; on the Argentine pampas, where indigenous megafauna had been exterminated, Spanish horses bred like rabbits. So the success of Europe's biological invasion, to Crosby, comes down in large part to Paul S. Martin's venerable "overkill hypothesis"—as deterministic an ecological explanation as anything in Diamond. The original settlers of the Americas were fated to slaughter native animal life, which could not adapt in time to fend off this new predator. This laid the ground for rapid reproduction of European species. Does the above narrative leave more room for agency and choice in native behavior? Crosby certainly does not indict the soon-to-be indigenes for overhunting the mammoth and the saber-toothed cat, nor should he have. Diamond follows this account, but emphasizes instead the destruction of potentially domesticable species, in line with his own mechanisms.

Europe, thanks to its geography, had a surfeit of domesticable animals and diseases, not to mention iron and steel weapons, while the Amerindians were still developing metallurgy. "Why," asks Crosby, "was the New World so tardily civilized?" (51). The answers to the question are deeply reminiscent of Diamond's. It's because the long axis of the Americas runs north-south, meaning that American food crops had to cross multiple biomes to diffuse across the continent, whereas Eurasian crops could travel laterally across similarly temperate terrain! And because American corn was far less domesticable than wheat, which yielded high returns immediately! "The first maize could not support large urban populations; the first wheat could, and so Old World civilization bounded a thousand years ahead of that in the New World" (49). Indeed, it seems possible that Diamond lifted all of this, with some tweaking, from Crosby. The two do differ slightly on the domestication of wild animals; Diamond cites the greater number of candidates in Eurasia, while Crosby suggests that differences in population pressure between the two continents may offer the real explanation—Eurasia had run out of room for continued extensive growth.

Either way, for Crosby the initial ecological conditions in Eurasia led to the early adoption of agriculture and the domestication of large animals like cows, sheep, and goats for meat and for traction power. Living in close proximity to livestock imposed a heavy disease burden on Eurasian farmers, but those who developed biological resistances and survived "prospered and multiplied," building cities, states, and empires. These societies could build ocean-going ships, and Iberian sailors, poised on the outmost tip of Europe, were best placed to master the wind patterns of the Atlantic. China's adverse regime changes snuffed out its dreams of empire, even though it too had the maritime technology—a concession to politics and human agency, true, but one that Diamond also makes.

For Crosby, as with Diamond, geography explains where Europeans conquered. Asian and Middle Eastern civilizations had equally benefited from the Old World Neolithic Revolution, and raised great fortresses, cannons, and janissaries against European advances. In the "torrid zones" of West Africa and Southeast Asia, Europeans found the climate unsuitable either for habitation—thanks to preference and disease—or for their crops and grazers, who met with competition from abundant wildlife. But in the temperate parts of the Americas and Australasia, the conquerors inadvertently found the conditions ripe for invasion—salutary climates with few diseases, soils suitable for the cultivation of wheat and barley, natives without the weaponry to effectively resist assault, and plains open for the herding of cattle. In these regions, European people, animals, and crops wiped out their counterparts and established Neo-Europes with "portmanteau biota" half-resembling the Old World.

Diamond's question is slightly different, so his answers and emphases are as well. But given the enormous structural similarities between the two works and the fact that Crosby explicitly seeks to downplay human agency in favor of natural causes, I fail to see how GGS can be regarded as more deterministic. And yet, despite the immense popularity of Ecological Imperialism, the popular outcry against geographical determinism has been levied against Diamond and not Crosby. Indeed, Crosby sometimes gets offered up as an alternative to Diamond that's more politically palatable. Perhaps Crosby, whose staunch anti-colonialism comes through loud and clear, speaks in a language that resonates more with Diamond's critics, who often share Crosby's political proclivities. But one cannot simultaneously argue that Diamond borrowed large parts of Crosby's argument and that the former is somehow more deterministic.

One work that has been suggested as an anti-Diamond "big history" combining a materialist analysis with "contingency and agency" is Kenneth Pomeranz's famous The Great Divergence (2000). Written three years after GGS, the book tries to explain economic inequalities within Eurasia—why Europe, and specifically Britain, was the heartland of industrialization rather than India or China (specifically the Yangtze Delta). To the naive reader, Diamond and Pomeranz couldn't be more different; the former is the paragon of the "long-term lock-in" school, while the latter is the modern champion of "short-term accident" theories of Western development, positing that the leading edge of Europe (Britain) was no more advanced than Asia's (the Yangtze Delta) as late as 1800.5

But such a shallow interpretation would be deeply misleading. Pomeranz emphasizes accidents, true—but geographical accidents. Like Diamond, Pomeranz wants to flatten differences between the West and the Rest—in institutions, science and technology, and internal ecology—to isolate a couple of key dissimilarities. Europe and China are shown to have similar institutions, and Pomeranz repeatedly pushes his thesis that Chinese markets more closely approached the Smithian ideal of perfect competition. Europe may have had an edge in capital accumulation, but ultimately it could only substitute for and increase the stock of land to a limited extent. You can have all the inclusive institutions, joint-stock companies, and mercantilism that you want, but if you can't find fuel and industrial raw materials, you can't have economic development. Ecological bottlenecks are poverty traps: when piece rates fall in proto-industrial sectors, workers increase output to maintain their consumption of food, glutting the market with cloth (say) and reducing prices even further. Coupled with rising populations, the land must be worked more intensively, "which with the technologies then available meant higher farm-product prices, lower per capita productivity, and a drag on industrial growth" (59).

So the eastern and western poles of Eurasia faced similar ecological constraints in terms of land and energy availability, in the face of which both would have been consigned to Asian-style labor-intensive production without some form of "external" relief. Though Pomeranz will admit some institutional and technological advantages on the European side, they were all but irrelevant in the face of the resource problem:

[W]hatever advantages Europe had—whether from a more developed “capitalism” and “consumerism,” the slack left by institutional barriers to more intensive land use, or even technological innovations—were nowhere near to pointing a way out of a fundamental set of ecological constraints shared by various “core” areas of the Old World. Moreover, purely consensual trade with less densely populated parts of the Old World—a strategy being pursued by all the core areas of Eurasia, often on a far larger scale than pre-1800 western Europe could manage—had limited potential for relieving these resource bottlenecks.

But Europe got that ecological relief—horizontally in the form of the New World's land endowment, and vertically, via England's easily-accessible coal reserves. American "ghost acreages" were secured by exactly the same mechanism as Diamond suggests: "epidemics seriously weakened resistance to European appropriation of these lands," followed by a wave of violent conquest by societies with military advantages. In Southeast Asia, already exposed to the Eurasia disease pool, "virgin soil epidemics" of the kind that Crosby and Diamond both emphasized did not sufficiently attenuate local political-military capacity to permit China to remake the region as a colonial dependency. Yes, Pomeranz does discuss institutional differences between the European and Chinese periphery—Europe used slavery and could thus choose the crop mix; China's peripheries were free and internal, replicating "core" production and blocking specialization—but the colonizers would never have been able to deploy slavery without the prior conquest of the Americas. Indeed, slavery is necessitated by the collapse of native populations; following Barbara Solow, Pomeranz argues that free labor was too expensive and Europeans were too poor to pay their own way, so Africans had to be coerced to take their place. The exploitation of British coal, meanwhile, was of course (for Pomeranz, at least) a stroke of good geographical fortune rather than a fruit of British ingenuity. That is, fuel reserves determined industrial success irrespective of human agency.

Coal and colonies, ecology and geography. If Pomeranz will not argue that India and China somehow failed to overcome their ecological constraints by making avoidable mistakes, then by the standards applied to GGS, his narrative does have its own elements of geographical determinism. Indeed, the shorter span over which his explanation operates actually makes it more binding than Diamond's framework, which permits fluctuations in the relative technological position of Europe and China as a result of contingent political factors, and operates chiefly on the broader divergences between Eurasia, Africa, and the Americas in the extremely long run up to 1500. Indeed, geography, which is static, can be more plausibly seen to "determine" events across extremely wide time horizons than upon sharp and shorter-run outcomes.

Of course, I am not asserting that Pomeranz is a geographical determinist per se. I don’t really think that he is. But he does make several claims which, by the standards applied to Diamond, would certainly make him one. Indeed, the condemnation of Diamond's determinism is even more laughable if you've read any of his other works. Collapse, for example, is literally subtitled "How Societies Choose [emphasis mine] To Fail and Succeed." Diamond urges his readers to take action to build a more sustainable future in the face of our present climatological disaster, which is of course avoidable. Entire sections are devoted to what people can do as individuals and what policies countries can implement to stave off deforestation, pollution, and global warming. He gives examples—some of which, admittedly, are wrong, which makes it even funnier—of human communities facing up to ecological challenges and creating prosperity nonetheless. How have those societies chosen to succeed? By making "bold, courageous, anticipatory decisions at a time when problems have become perceptible but before they have reached crisis proportions." If that's not a dramatic assertion of human agency, then I haven't a clue what is.

Excuses and Epidemics

Accusations of geographical determinism, however, would fall flat on the reading public if they didn't contain a more inflammatory insinuation. Armchair critics of Marx, for example, rarely expostulate (solely) about his deterministic framework; the same could be said of the foes of neoclassical economics. Even Milton Friedman, incidentally, would struggle to match the legions of anonymous Redditors dedicated to denouncing GGS every time it is mentioned. And even Friedman has his legions of diehard fans.6 Their rambling critiques drip with scorn and fury. r/AskHistorians has an entire section of its FAQ dedicated to them. A recent query about historians' views on the book got the following reply: "Take it back to the bookshop and ask for your money back. Then chat up Kronos and see if you can get back the time you spent reading." Yikes! Why, then, do academics (and adjacent) just despise Jared Diamond?

One historian, to popular Twitter acclaim, suggested that the main problem with Diamond is that "[h]e uses geography to explain horrible things done by colonialism, which makes this stuff natural and not anyone's fault." This is a catastrophic error, reflecting a basic, likely wilful misreading of Diamond's work. As I have noted before, his explicit aim is to explain the rise of Eurasia, and specifically Europe, without reference to inherent European biological and cultural advantages. He explicitly condemns popular histories that emphasize biological and cultural superiority as racist. Guns, germs, seeds, or steel did not make it inevitable that Europeans would invade the Americas and annihilate native populations. I mean, why would Diamond even want to argue this? But it reflects a strain of GGS ripostes that have seized the academic imagination since the book's publication.

Anthropologists appear to be the most infuriated by Diamond's publishing success. Indeed, a 2006 meeting of the American Anthropological Association was convened to debunk Diamond's work, resulting in a volume called Questioning Collapse. It's as though the American Economic Association called a special session to discuss methods of purging the heresies of Marx from modern society. The anthropologist Barbara J. King speculated that the reason may merely be that Diamond has written "big books" about early human history while anthropologists haven't (at least since the 1980s).

Antrosio

The anthropologist Jason Antrosio really hates GGS, calling it "academic porn" and demanding that it be stricken from introductory college anthropology courses. His critique—if one can call it that—revolves around his suggestion that Diamond puts the causes of European imperialism in the distant past and attributes them to geography, which removes the blame for their misdeeds. He approvingly quotes another scholar: "For Diamond, guns and steel were just technologies that happened to fall into the hands of one’s collective ancestors. And, just to make things fair, they only marginally benefited Westerners over their Indigenous foes in the New World because the real conquest was accomplished by other forces floating free in the cosmic lottery–submicroscopic pathogens" (Wilcox 2010, p. 123). Incredibly, Antrosio tendentiously explains that "[w]hat Diamond glosses over is that just because you have guns and steel does not mean you should use them for colonial and imperial purposes."

Unfortunately, Antrosio never actually quotes Diamond, whose books I presume he is afraid to remove from the standing desk in his office.7 If he had tried to read them, he might have changed his views (I am being a little charitable, granted), because even a cursory glance at the text reveals that his interpretation is sheer invention. Diamond's goal is to "identify the chain of proximate factors that enabled Pizarro to capture Atahuallpa, and that operated in European conquests of other Native American societies as well" (28). That's right, enabled Pizarro, not forced Pizarro. He is careful to use the word "permitted" on the following page. The conquistadors were not compelled by the swords and guns to sail across the Atlantic and spread disease, but by the desire for land and loot. "Once Spain had... launched the European colonization of America, other European states saw the wealth flowing into Spain, and six more joined in colonizing America" (413). He even suggests that Western culture, namely Christianity, was a "driving force" behind European expansionism.

In discussing specific instances, Diamond speculates that "Pizarro's men," he writes "formed the spearhead of a force bent on permanent conquest" (79). He unsparingly describes how Pizarro reneged on his promise to Atahualpa and executed him after extracting an enormous ransom. Of the collapse of the native populations "discovered" by Columbus, Diamond writes that "the island Indians, whose estimated population at the time of their "discovery" exceeded a million, were rapidly exterminated by disease, dispossession, enslavement, warfare, and casual murder" (373). Of the conquest of Australia: "The reason we think of Aborigines as desert people is simply that Europeans killed or drove them out of the most desirable areas, leaving the last intact Aboriginal populations only in areas that Europeans didn't want" (310). For those complaining that Diamond doeesn't take "sides," well, there's more where that came from.

Antrosio further indicts Diamond because he "has almost nothing to say about the political decisions made in order to pursue European imperialism, to manufacture steel and guns, and to use disease as a weapon." GGS is not a political history, and neither Antrosio nor Diamond is a political historian, so this remark is puzzling. Nevertheless, the latter directly addresses this point (i.e. that the extermination of native populations was in some part the result of political decisions):

We know from our recent history that English did not come to replace U.S. Indian languages merely because English sounded musical to Indians' ears. Instead, the replacement entailed English-speaking immigrants' killing most Indians by war, murder, and introduced diseases, and the surviving Indians' being pressured into adopting English, the new majority language (328).

Native Allies

Finally, Antrosio argues that Diamond underplays (deliberately, in his suggestions of malice) the role of native allies in the Spanish conquest. This reading, however, demonstrates a failure to understand the distinction between proximate and ultimate causes. Diamond does not discount the fact that native allies assisted the Spaniards in seizing the Americas. He is more concerned that Spanish victories should not be "written off as due merely [emphasis mine] to the help of Native American allies" (75) and a range of other non-material factors. Native forces had some part to play, as they self-evidently did in most European imperial settings. If no one cooperated with an invading force, and if everyone joined the resistance, it would be difficult indeed to suppress a settled agrarian civilization. Nazi occupation in Europe would not have succeeded without collaborators and quiescence from locals just trying to stay out of the way.

Nevertheless, Diamond's suggestion is that Native peoples would have found it irrational to help tiny bands of Spaniards if they did not possess some military advantages. Contrary to many Reddit screeds against the book, he does not emphasize firearms. Instead, he attributes the Spanish combat advantage primarily to steel:

In the Spanish conquest of the Incas, guns played only a minor role. The guns of those times (so-called harquebuses) were difficult to load and fire, and Pizarro had only a dozen of them. They did produce a big psychological effect on those occasions when they managed to fire. Far more important were the Spaniards' steel swords, lances, and daggers, strong sharp weapons that slaughtered thinly armored Indians. In contrast, Indian blunt clubs, while capable of battering and wounding Spaniards and their horses, rarely succeeded in killing them (76).

Even Matthew Restall, whose Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (2003) is supposed to be the "better" conquest history, argues that the steel sword (after disease!) was a key factor in Spanish military success.

It's true that Diamond's focus on the dramatic destruction of the Inca empire elides the more difficult task facing Cortes against the Aztecs, and how his force may have faced annihilation without the aid of several Tlaxcalan factions (who thought an alliance profitable in the midst of their civil war). Yet even Charles Mann, another critics' favorite, writes that "[t]hanks to their guns, horses, and steel blades, the foreigners won every battle, even with Tlaxcala’s huge numerical advantage" (191). Instead of trying to wipe out Cortes, which might have succeeded, albeit at great cost, the Tlaxcalans made a "win-win" pact with the Spaniards to take down their mutual foes. This is exactly the mechanism that Diamond is talking about! Small military force wins initial victories thanks to initial military superiority, convincing allies to join on their side.

Incidentally, Native allies did not reverse the Spaniards' numerical disadvantage. When the Spaniards escaped Tenochtitlan, they numbered at most 1,300, many sick or wounded, along with just 96 horses. They were aided by 5,000-6,000 Tlaxcalans, who were unlikely to have many martial advantages over trained Aztec warriors. The city's population was estimated at the time to have been over 200,000. If just ten percent were fighting-age males, the Spanish faced difficult odds. A week later, at the battle of Otumba, 425 Spaniards and 3,000-3,500 Tlaxcalans defeated an Aztec force of 200,000—a feat that would still be impressive if the Spanish exaggerated their enemies' numbers by ten times. At Cajamarca, the Spanish defeated Atahualpa's bodyguard of over 5,000 with only 168 men, just 62 mounted. At Quito, an Inca army of 50,000 was reportedly defeated by 200 Spaniards and 3,000 Cuzco allies.

Neither Diamond nor I suggest that Native soldiers, acting for their own advantage, were unimportant to Spanish success. That question is unanswerable on the basis of the existing evidence. But Diamond's more conservative point—not just Native allies—seems reasonable on the basis of the facts that we do have. It would have been remarkable if native uprisings just happened to topple the ancient and powerful Inca and Aztec civilizations precisely at the moment the Spanish arrived. Why hadn't they done so earlier—especially if disease was already suppurating across the Americas?

Virgin Soil Theory

Amazingly, some critics have also argued that Diamond also "naturalizes" global inequalities by supporting Crosby's theory of "microbial determinism." That is, arguing that waves of smallpox killed the preponderance of Native Americans before the conquistadors reached and established control over many regions is said to be akin to exculpating the Spanish. The American historian Jeffrey Ostler, for example, argues that "virgin-soil epidemics were not as common as previously believed" and that we should focus on "how diseases repeatedly attacked Native communities in the decades and centuries after Europeans first arrived." This temporal shift allows us to show that "[p]ost-contact diseases were crippling not so much because indigenous people lacked immunity, but because the conditions created by European and U.S. colonialism made Native communities vulnerable." Thomas Lecaque, writing in Foreign Policy, echoes this point, citing three different works... by the same historian... as evidence of a literature showing that the "virgin-soil thesis" has been "debunked." Diseases weren't a historical accident; the Spanish and the US government did it on purpose.

What is the revisionist position, and what's the evidence behind it? Ostler and Lecaque's pieces are digressive and expostulatory, so it's difficult to sort between evidence and invective. Ostler's article admits that there were some virgin soil epidemics. But those that did happen, he claims, were exacerbated or deliberately carried out by the colonial powers. The De Soto expedition, for instance, caused dysentery outbreaks because of its "violent warfare," but didn't just accidentally spread smallpox, as some previous (and uncited) scholars alleged. Ostler neglects to mention, however, that members of the party reported “large vacant towns grown up in grass that appeared as if no people had lived in them for a long time. The Indians said that two years before, there had been a pest in the land, and that the inhabitants had moved away to other towns” (quoted in Harper 2021, p. 278). De Soto's own contacts, meanwhile, were too limited to have done much to spread disease. In other words, epidemics (at least in the US Southeast) raced in advance of the conquistadors—as the virgin soil thesis would have it.

Ostler contends that smallpox itself did not reach (some) communities in the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes regions until the 1750s (this seems difficult to corroborate), and it only arrived because of Native fighters returning from participating in the French and Indian War. Even if he's right, war's role is inconsequential here and in no way contradicts Diamond's version of the VST. Natives moving along trade routes passed European diseases along to their neighbors, producing devastation often (not always) without European help. Thus the conquerors found once-proud civilizations easier to defeat when they arrived in person.

Ostler then flashes forward in time, to discuss the interactions between natives, disease, and the US government. He makes the point that in the 19th century, smallpox virulence correlated not with a lack of prior exposure, but with poverty. "These same conditions," he writes, "would also make Native communities susceptible to a host of other diseases, including cholera, typhus, malaria, dysentery, tuberculosis, scrofula, and alcoholism. Native vulnerability had—and has—nothing to do with racial inferiority or, since those initial incidents, lack of immunity; rather, it has everything to do with concrete policies pursued by the United States government, its states, and its citizens." I am a little bit dismayed by the moral code that leads the revisionists to feel that "vulnerability to pathogens they've never experienced before" would render the natives "inferior"—am I an ubermensch because I never get sick? Ostler then writes of the Trail of Tears, where 25 percent of 16,000 Cherokee died during relocation from the US Southeast. 85 percent of the Sauks and Mesquakies of Western Illinois died or disappeared between 1832 and 1869, though it's not clear what the proportions attributable to disease, murder, slackened fertility, and out-migration are.

The problem is that Ostler is talking about the wrong time period. No doubt Native populations inside and outside the American colonial empires continued to decline after the conquest, in large part thanks to the horrific behavior of the conquerors. But Diamond and Crosby are chiefly concerned with the initial waves of disease that swept out in front and raced alongside the conquering bands of Spaniards as they rampaged across the Americas. They seek to explain the initial European victories against much more populous Indigenous civilizations; thus referencing the Trail of Tears—a tragic and significant event in a later story—is at best a red herring in this one. Qualitative narrative data exists in abundance to corroborate the role of disease in this first encounter. On Hispaniola, for example, there were epidemics in 1493-94, 1496, 1498, 1500, 1502, and 1507. By 1520, Spanish observers were reporting that the island had been substantially depopulated, and by the end of the decade, there were virtually no native inhabitants at all, out of an original population that may have been in the low millions. Since only a few thousand Spaniards ever settled in the Caribbean at large (many of whom were largely inoffensive priests), it seems implausible to attribute all or even most of this to murder, fertility decline, or the forced-labor system. And even if you embrace an interaction between brutality and plague mortality, I don’t think that you thereby torpedo Diamond’s hypothesis.

In 1518-19, a smallpox epidemic broke out in the Caribbean, and in 1520, thanks to the Cortes and Narvaez expeditions, it spread into Mexico. By the end of the year, a letter to Charles V already documented high levels of depopulation resulting from disease. The Florentine Codex, written by Bernard de Sahagun, who learned Nahuatl (the Aztec language) for the project, reports Aztec testimony about the events: “Before the Spaniards had risen against us, first there came to be prevalent a great sickness, a plague . . . there spread over the people a great destruction of men. Some it indeed covered [with pustules]; they were spread everywhere, on one’s face, on one’s head, on one’s breast, etc.” The following year, Cortes returned to Tenochtitlan (from which he had retreated in 1520) to find the city's defenders decimated by disease—indeed, many of the leaders had died. With smallpox coursing ahead of him along Aztec trade routes, Cortes quickly consolidated his conquests. In the Andes, meanwhile, an outbreak of smallpox apparently killed the Inca emperor Huanya Capac, most of his court, and his heir-designate Ninan Cuyuchi, precipitating a succession war between Atahualpa (who was defeated by Pizarro) and his half-brother Huascar. Given that the leaders of the Aztec and Incan empires were likely the least impoverished individuals in the Americas, the fact that both cadres suffered badly from disease indicates the severity of the epidemics loosed by the Spaniards.

Lecaque, making a similar point, rests his case (he just cites the same guy over again) on a similar body of research, spearheaded by the historian Paul Kelton. Kelton co-edited a compilation of articles—Beyond Germs (2015)—disparaging the virgin soil hypothesis (VSH) on the grounds that a range of social factors (usually colonialism) are as if not more important. The volume and its essays are not coherent and demonstrate a weak understanding of the VSH. Kelton's own article, for example, deals with the Cherokee experience of smallpox during the American Revolution, and argues that the evidence for disease damaging population sizes is weak; instead, the scorched-earth tactics of American armies was more important (at least per Cherokee testimony). That may be, but he's talking about an event that occurred over 250 years after the Spanish arrived in the Americas. It has absolutely nothing to do with the explanation for why European states were so militarily successful in the first place.

The only essay in the book that really tries to systematically confront the VSH is that of David S. Jones. Jones, a former medical student, appears to have rankled at the suggestion that Native Americans had "no immunity" to European disease, responding with the incredibly banal point that everyone has an immune system. His essay complains about the prevalence of the genetic determinist school of explanations for native depopulation, cataloging case studies of instances in which exposure to disease appears to have followed the implementation of colonial violence. Some of these examples are either weak or irrelevant: Indigenous Canadians, for example, saw lower mortality rates (according to studies that he cites!) largely because of their low population densities and the cold climate surrounding Hudson's Bay. Even still, Carlos and Lewis (2011) note that the limited population declines noted by European explorers are highly uncertain because... disease traveled out in front of them.

But Jones concludes that even low pre-contact population estimates imply enormous rates of mortality, on the order of 75%. He suggests that there are two possible explanations: “shared genetic vulnerability, whose final intensity was shaped by social variables” and “pre-existing nutritional stress exacerbated by the widespread chaos of encounter and colonization” (40-41). Referring back to his 2003 survey essay on the same topic, Jones repeats his prior conclusion that high mortality was “a likely consequence of encounter,” but not “necessarily” the inevitable result of immunological vulnerability to European diseases. This, he concedes, was a "hedge," and he notes that he had and has no way to answer the question. To say that either the "determinists" or the contingency school could be right, but that the evidence doesn't support a definitive conclusion, is pretty weak stuff insofar as a VSH critique goes. It’s also telling that Jones actually sacrifices the argument that the Americas were populous and prosperous prior to contact to advance his view that genetic vulnerability was a non-factor.

The authors frequently base their arguments on the suggestion that without the effects of European settlement that followed the disease outbreaks, native populations would have recovered. But again, that's beside the point. Diamond, and to some extent Crosby, focus on why Native Americans were unable to resist the small, unprofessional bands of conquistadors, and not why their populations continued to decline. The authors of Beyond Germs and their intellectual fellow travelers, by contrast, just assume European supremacy and start looking for effects. Diamond is concerned with why forced labor regimes and deliberate depopulation could be conducted in the first place.

No doubt some crude right-leaning histories, for instance, Jeffrey Flynn-Paul's Not Stolen (2023),8 attempt this historical gambit, but Diamond does not. In no way does he dance around the question of agency in the destruction of native populations. On page 15, for example, he writes that "the aboriginal inhabitants of Australia, the Americas, and southernmost Africa, are no longer even masters of their own lands but have been decimated, and in some cases even exterminated by European colonialists" (15). Two pages later, he adds that "many other indigenous populations—such as native Hawaiians, Aboriginal Australians, native Siberians, and Indians in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, and Chile—became so reduced in numbers by genocide and disease that they are now greatly outnumbered by the descendants of invaders" (17). That's right—genocide and disease, working in tandem.

Respected accounts of the conquest—those proposed as alternatives to Diamond—also heavily emphasize disease, seeking to dispel the suggestion that European technological advantages were significant. Charles C. Mann writes in his oft-acclaimed 1491 (2005) that "the pain and death caused from the deliberate epidemics, lethal cruelty, and egregious racism pale in comparison to those caused by the great waves of disease, a means of subjugation that the Europeans could not control and in many cases did not know they had" (200). Indeed, deliberate attempts to exterminate indigenous populations generally postdated the initial phases of the Spanish conquest; during this phase, the Spanish were actually mortified that their supplies of cheap labor were dwindling so rapidly, plunging the colonies into economic depression. He memorably relates the debate between the High Counters and the Low Counters on the pre-contact population of the Americas, suggesting that the former—those with numbers ranging from 40 to 100 million—have gained the ascendancy. The higher the count, the stronger the case for plagues sweeping ahead of the conquistadors and leveling their foes, and vice versa. For Mann, only calamitous epidemics could explain why kingdoms that resembled European states fell to small bands of armed thugs and their local allies. And since many scholars have reverse-engineered pre-conquest populations from assumed death rate, the greater the mortality, the larger the original population.

Matthew Restall's Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (2003), another oft-mooted Diamond surrogate, also accords a central role to disease. He uses the great plagues to dispel the "Myth of Superiority" cultivated by the conquistadors and their defenders. He writes quite succinctly that

For ten millennia the Americas had been isolated from the rest of the world. The greater numbers of people in the Old World, and the greater variety of domesticated animals from which such diseases as smallpox, measles, and flu originated, meant that Europeans and Africans arrived in the New World with a deadly array of germs. These germs still killed Old World peoples, but they had developed relatively high levels of immunity compared to Native Americans, who died rapidly and in staggeringly high numbers. During the century and a half after Columbus’s first voyage, the Native American population fell by as much as 90 percent (141).

For that passage, he cites... Jared Diamond. Incidentally, he also follows Diamond in emphasizing the importance of steel swords and the relative paucity of firearms, and in general, his criticisms of GGS are relatively mild.

The most coherent critique I've read of the VSH is Livi-Bacci (2006). The demographer applies some basic epidemiological logic to the problem and then backs it up with regional case studies. Much of that analysis is based on his assertion that, in a "virgin" population, the lethality of smallpox is 20-50 percent (contingent on age), rather than the 80 percent rate wrought by plague. That's quite a step, mind you, because it rejects out of hand—without much supporting evidence—the possibility of achieving the 95 percent decline figure offered by Diamond (who cites Dobyns).

He then applies this figure to a hypothetical population of 1000. 400 die in the first wave. Assuming that birth rates maintain the population at 600 over the next 15 years, a second and third outbreak will reduce the number of survivors to 423—a 60 percent decline in 30 years. But these assumptions are unrealistic. 40 percent is at the high end of (note: observed) mortality figures. Not everyone in the community will be infected. And population would be unlikely to remain stationary between the pandemics unless some outside force (read: the Spanish) curtailed fertility. Assuming 70 percent infection rates, a declining case mortality rate (40 percent in the first wave, 30 percent thereafter), and 1 percent population growth per year, the size of the population should stand at 901 individuals after thirty years and three epidemics. That's a tragedy, but still a far cry from 95 percent.

But this model does not fit the historical context particularly well. First, Livi-Bacci's estimates (derived from Dixon (1962)) of the fatality rate of smallpox are more recent observations that may be contaminated by built-up resistance to the disease. There's a reason why the Spanish didn't die as frequently! Second, the model does not incorporate the interaction of smallpox with the raft of other diseases that wracked the New World during the Spanish conquest, from plague and measles to typhus, typhoid, and various fevers. The interaction between these pathogens may have significantly elevated their respective fatality rates by overloading immune systems and hitting populations with higher frequency than one disease alone could have. Finally, epidemics did occur more frequently than fifteen years at a time. On Hispaniola (see above), disease struck every two years during the terrible 1490s. These excluded factors suggest that Livi-Bacci substantially underestimates disease mortality.

Livi-Bacci develops three case studies to illustrate his point, comparing the demographic effects of "good" and "bad" Spanish institutions in the New World. Of the Taino people of Hispaniola, he argues that the disastrous mortality that they suffered need not be explained by either the "Black Legend" of "exceptional" Spanish cruelty or the virgin-soil paradigm, but rather by the "confiscation" of native labor. In addition, the Spanish took many Taino women as wives and concubines, unbalancing the gender ratio, while social dislocation—worsening living standards and the disruption of family and village ties—reduced the fertility of those who weren't removed from the marital pool.

Livi-Bacci also disputes the suggestion that smallpox invaded the Inca Empire ahead of Pizarro. He asserts that "[e]pidemiologists would characterize this hypothesis [that disease could spread rapidly across thousands of miles overland by face-to-face contact] as improbable, if not impossible." While disease did eventually arrive, and while sixteenth-century mortality was probably catastrophic in Peru—the Huanca tribe fell from 27,000 members in the 1520s to 7,200 in 1572; the Chupachos of Huanuco from 4,000 to 800 over a similar span—the cause was probably (or at least partly) civil war. Livi-Bacci's evidence is sparse, mostly consisting of a single traveler's account, but he also shows that the Huanca had, by 1558, lent out 27,000 men to the Spanish armies (1,800 per year) out of an original population of 12,000 (declining to 2,500 by 1548). The Spanish had also taken large quantities of foodstuffs and pack animals.

His counterfactual is the relatively good institutional matrix of Guarani Paraguay, where Jesuit missions protected the Indios from the ravages of Portuguese slave traders. Under the auspices of the fathers, who kept their converts in planned villages under strict administration, the Guarani population increased from 40,000 to over 140,000 from the 1640s to the 1730s. Despite high mortality events, Livi-Bacci argues, the institution of early and monogamous marriages led to a high fertility rate (7.7 births per woman) that allowed swift recovery from demographic shocks.

But is this counterfactual appropriate? Livi-Bacci does not have data prior to the mid-17th century, and so is unable to make particular claims about the true effect of Jesuit institutions on Guarani demography. What did fertility patterns look like among the Guarani prior to the implementation of written Spanish records? Nor is he able to precisely gauge the effects of smallpox during the 16th century and how that may have dampened the effects of the disease during the period in which data is available. Nor, finally, is Paraguay a particularly good counterfactual for the main American civilizations that are the focus of Diamond's work. The Guarani were, by Livi-Bacci's own telling, an isolated and sparse group with minimal integration with the outside world. Prior to the Jesuit missions, their nomadic populations could simply relocate to escape outbreaks of disease. A similar situation prevailed in northern Canada, where (as noted above) the Cree (probably) escaped smallpox until the late eighteenth century thanks to low population densities and a frigid climate. There's reason to believe that these groups were not representative of the civilizations that faced the initial Spanish conquests.

Diamond's critics would like to have it both ways. On the one hand, they refuse to concede that Europeans had any significant technological or military advantage over Native American civilizations, because that would connote some kind of intrinsic superiority of the former over the latter. On the other hand, however, they want to show that deliberate European manipulation and control over Indigenous peoples led to population decline—a level of imperial mastery that could only have been maintained with some sort of military disparity. Diamond's explanation is much simpler: Europeans won initial victories because of guns, germs, and steel (plus horses, literacy, and ships) and then, after establishing their own colonial regimes, induced further depopulation through impoverishment, coercion, and outright murder—yes, he calls it genocide. Europeans committed horrific crimes that were not inevitable and germs enabled them to do it.

As an aside, it takes a very strange ethical system to claim that lowering the direct casualties of Spanish conquest from 15 million to 150000 (for instance) is somehow an ‘excuse’ for imperialism. Everyone agrees on the fact that the Spaniards did conquer the Americas, shatter indigenous customs, and implement forced-labor regimes. Those policies were horrific regardless of whether the number of victims is large or astronomical, and whether or not they led to the Spanish conquest of the Americas is, in my view, a drop in a bucket of moral sludge. But since Diamond doesn't even attempt these rhetorical gymnastics, the criticism is wrong either way. Moreover, whether Diamond is factually correct about the 95 percent mortality figure is not that relevant to his main question—why Europeans prevailed in the first place.

Eurocentrism

We've already met one of Diamond's more prominent and earliest academic critics, James Blaut, also an anthropologist. Blaut includes Diamond in his Eight Eurocentric Historians (2000), alongside Max Weber, Lynn White, Robert Brenner, Eric Jones, Michael Mann, John A. Hall, and David Landes. It's somewhat perplexing to tar GGS with the brush of Eurocentrism, considering that it's primarily focused on Eurasia rather than Europe per se.9 Diamond's vice is "Euro-environmentalism," or falsely claiming that Europe's environment is superior to those of other continents. Blaut's reading, however, is pure fantasy—the language of "superiority" and "inferiority" is his own insertion into a book devoid of such terms. Why would the fragmented geography of Europe make it a "better" place to live than China?

Blaut is enraged by commonplace aspects of the book's language. For example: "'Environment molds history,' says Diamond flatly and without qualification" (150). Is this supposed to be some sort of gotcha? If you don't think that the environment has an effect on historical trajectories, which is all that Diamond is saying, then you're actually making a stronger and more controversial (not to mention incorrect) claim. In addition, Blaut objects to Diamond's use of the phrase "natural experiment" to describe a comparison between two societies operating in nearby but different ecological zones. Yet this is a standard methodology in the social sciences for estimating causal effects.

Next, Blaut fulminates against Diamond's explanation of the origins of agriculture. He makes the bizarre objection that the Americas are almost as wide as Eurasia, and that Eurasia is almost as tall as it is wide, ignoring the equally important points in GGS concerning the importance of ecological barriers to technological diffusion. His objection that Eurasia is full of trackless deserts is mostly irrelevant, as Diamond actually suggests that Europe and the Indus Valley got their agriculture from the Near East, while China supplied East Asia with some assistance from Mesopotamia. Indeed, Diamond himself writes that the "temperate areas of China were isolated from western Eurasian areas with similar climates by the combination of the Central Asian desert, Tibetan plateau, and Himalayas" (189). Blaut then tries to create uncertainty about the archeological record, complaining that archaeologists have been digging in Mesopotamia for longer and speculating that other sites will eventually reveal much earlier dates—including another site in Southeast Asia that, around 7,000 years ago, might have sunk like Atlantis into the sea!

Blaut claims that Diamond does not explain why the Mediterranean climate zone is particularly suited for the origins of agriculture; on the contrary, Diamond does, emphasizing that Mediterranean crops grow rapidly with the first winter rains and that they have large, edible seeds that can be stored. He does not deny that large-seeded crops grew elsewhere (see above) or that crops without large seeds could be domesticated. Eurasia just had the weight of numbers: of the 56 known large-seeded grass species, 32 could be found in the Mediterranean and just 11 in all of the Americas combined. Of the 14 species of ancestrally domesticated animals, 13 lived in Eurasia, none in Sub-Saharan Africa, and just one in the Americas. Seven of the Eurasian species were resident in or near the Fertile Crescent. In any event, the main significance of the Mediterranean climate zone was as a vector for the spread of agriculture.

Blaut then claims that Diamond is "not satisfied" with the "conventional scholarly answer" to the question of why Europeans conquered the Americas—that is, that the Americas suffered in part from lower technology vis-a-vis the Spaniards, but more from diseases. Diamond's explanation is if anything A) a moderate reweighting of the two factors and B) a revision of the ultimate causes behind them. Blaut thinks that the real answer is that the Americas were settled later than Eurasia. Fine. But how does that explain the disease disparity? And how does that do more to escape the trap of environmental determinism? Indeed, it poses an even stricter relationship between geography and technology—later-settled regions are behind earlier-settled ones in proportion to the difference in dates of settlement.

Blaut goes on to suggest that there is no desert barrier between northern Mexico and the central-eastern US. In fact, the Mexico-US border is almost entirely covered by three desert ecoregions: the Sonoran Desert to the west, the Chihuahuan Desert in the center, and the narrow band of the Tamaulipan Mezquital (still a desert) on the eastern side. His claim that Diamond "wants to show that Eurasia's importance in animal domestication was one of the primary reasons why temperate Eurasia (supposedly) gained superiority in subsequent cultural evolution" (163) is bemusing: Diamond is trying to extirpate the notion that Europe's cultural evolution was particularly important. He frequently resorts to historical anachronism: suggesting pathetically that the only attempt to domesticate the zebra was a 19th-century European failure (why hadn't it been domesticated in the previous few millennia?) and that modified disease-resistant cattle thrived in Africa (reminder to any time lords in the vicinity to teach pastoralists about germ theory).

After dismissing Diamond's arguments about continental axes and the scientific evidence on the origins of agriculture, Blaut concludes that there's not much left of Diamond's thesis. Unfortunately, the same can be said of Blaut—after we reject his dismissals, there is really nothing of substance left in his critique. Blaut concludes that "[g]eography is important, but not that important" (165). How important is that important?

Finally, we reach the only part of GGS that can justifiably be included in a critique of "Eurocentric" historians: Diamond's short epilogue comparing Europe and China. Aside from Blaut's sloppy characterization of the "development of a merchant class, capitalism, and patent protection for inventions" as cultural factors, I agree that they constitute a classically "Eurocentric" set of causes for European economic development. That doesn't necessarily mean that they're not important, but they are things that Eurocentric historians say. Blaut has Diamond saying that China was unified 2,000 years ago because it does not have high mountains like the Alps or a coastline with large bays and inlets that divided regions into separate cores; Europe, by contrast, could never be unified because of these features. Since empires must always be despotic, Chinese emperors oppressed and overtaxed their people, while Europeans slouched toward democracy. The former produced stagnation, the latter capitalist development.

Is that really what Diamond says? No, he doesn't just discuss "capes and bays," as Blaut suggests. Instead, Europe had five large peninsulas that developed into political, cultural, and linguistic zones, against East Asia's one (Korea), along with two large islands that were reasonably close to the mainland. European fragmentation was also facilitated by several mountain ranges—the Alps, Carpathians, Pyrenees, and Norwegian border ranges—that assisted in core formation. China's eastern mountain ranges were not as divisive. Additionally, the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers bound together the Chinese heartland with two fertile alluvial basins from east to west, and transit north-south between them was relatively straightforward (and eased by the construction of canals). Europe's two largest rivers, the Rhine and the Danube, are smaller and do not travel in directions that would assist in interconnecting core regions. Thus "China very early became dominated by two huge geographic core areas of high productivity, themselves only weakly separated from each other and eventually fused into a single core... Unlike China, Europe has many scattered small core areas, none big enough to dominate the others for long, and each the center of chronically independent states" (414).

Blaut completely misunderstands the argument. "[T]he historical processes Diamond is discussing pertain to the last 500 years of history, and most of the major developments of this period, those that are relevant to his argument, occurred mainly in northern and western Europe, which is rather flat" (169). But the four great powers of early modern Western Europe—Spain, France, the Dutch Republic, and England—can attribute their existence in part to the exact geographical boundaries that Diamond describes.10 Blaut adds that "[t]he idea that the pattern of multiple states somehow favored democracy is a misconception: each of these states was as despotic as—probably more despotic than—China" (169). This is not only a red herring—Diamond is not talking about democracy, but rather that interstate competition allowed innovators to escape to more friendly polities—but also just wrong. Early modern Europe housed multiple states that were much less despotic than China, Bourbon France, and Habsburg Spain, from the Dutch and Venetian Republics to, well, England. Interstate competition was, at least in some cases, a catalyst for democratization—the huge expenses incurred by raising militaries required monarchs to gain Parliamentary approval on extraordinary taxes.

Blaut compounds these errors by arguing—sans citation—that domestic peace and the lack of internal borders encouraged market development and innovation in China. But the critics of the "bellicist" view espoused by Diamond have contended the exact opposite—that China was at war just as much as Europe. According to Hoffman (2015), China was at war 56% of the time between 1500 and 1799; England 53%; France 52%; Spain 81%; and Austria 24%. And even if there was a common market effect, Blaut offers no evidence (just extrapolation even wilder than Diamond's) that it counterbalanced the "despotism" drag (or the simple disadvantage of only being able to try one style of economic policy at a time). In short, Blaut's critique fails in large part because he exacerbates Diamond's tendency to make unfounded generalizations about specialist historical literatures.

Like Blaut, many GGS critics seize upon the final chapter and claim that its weaknesses damn the book. That's a shoddy bit of legerdemain. While Diamond's discussion of the rise of Europe is undoubtedly one of the weaker parts of the book, it's also basically tangential to his main thesis, which is directed at the long-term origins of Eurasian political-economic primacy in the 16th century. Diamond himself calls it an "extension" of the model. Aaron Jakes, for example, just dismisses the first 410 pages—"a decent synthesis of existing literature on the historical conditions of differential immunity and technological endowments at the moment Europeans encountered the 'New World'"—to focus on pages 409-417 (assuming he read either segment).

Diamond explains the ecological difficulties of the Near East without recourse to "speculations about bumpy coastlines." Low rainfall meant that plant growth could not keep up with the rate of overgrazing and deforestation; this in turn led to erosion, the silting up of valleys, and salt accumulation. Forests and grasslands became deserts—thanks not to innate characteristics of Middle Eastern farmers, but a common tendency to deplete the environment interacted with a climate that was more sensitive to long-term exploitation (and got worse over time).

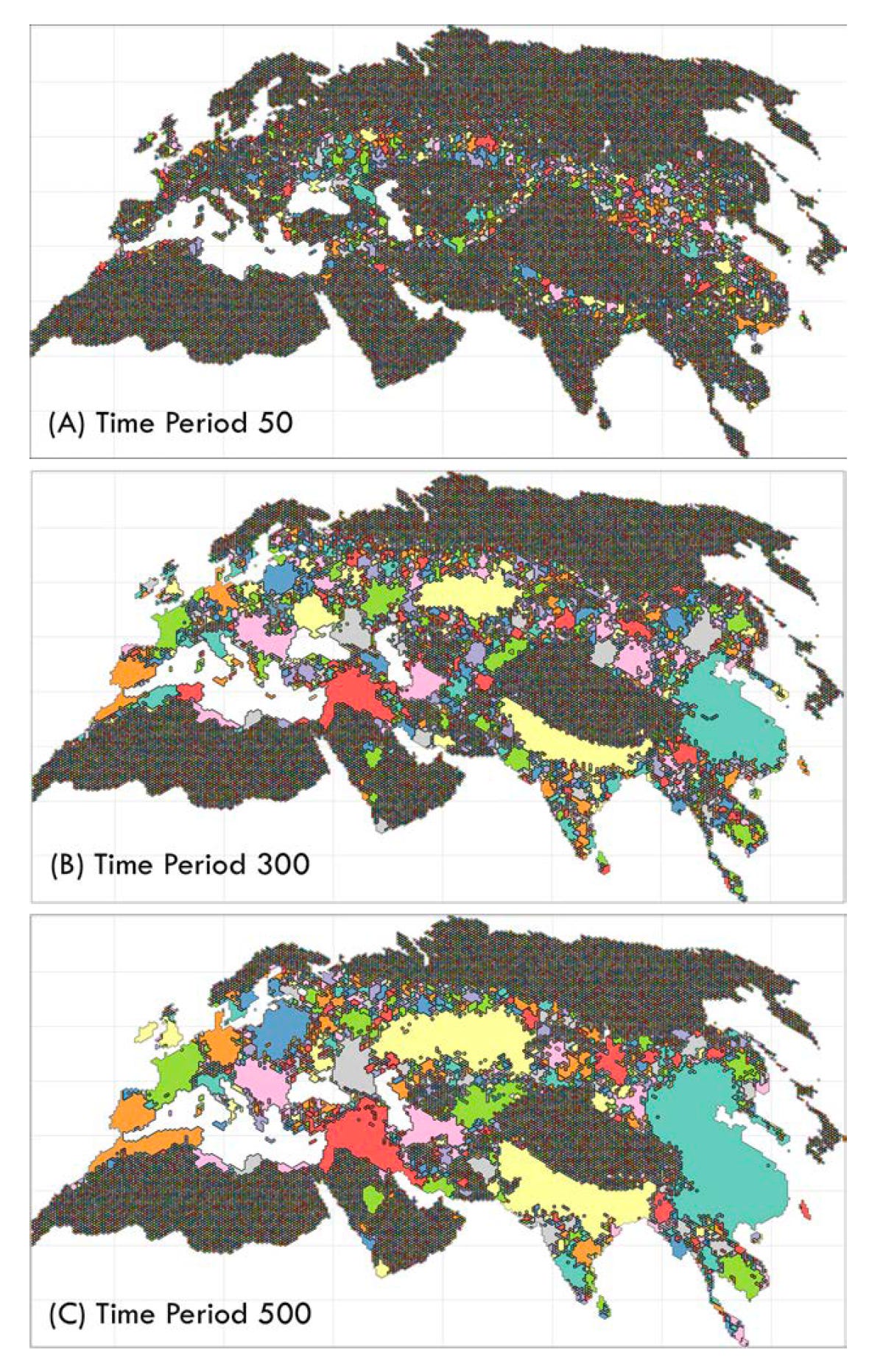

But how stupid are Diamond's "speculations" on the causes of European economic hegemony? The "fractured-land hypothesis" has bounced in and out of favor, but seems to have returned. Fernandez-Villaverde et al. (2022) recently revisited the question. Dividing the world into a hexagonal grid of polities to represent a world prior to state formation, they construct a probabilistic model of military conflict and territorial acquisition in which the productivity of each grid-cell influences the chance that the controlling polity will be able to absorb neighbors. The authors simulate the model and show that, lo and behold, this simple framework produces a very Diamond-like world by 1500. French, British, German, Iberian, and Northern Italian polities occupy the obvious core areas of Europe; an Ottoman Empire covers eastern Anatolia and the Levant; and super-states stretch across northern India and eastern China. The model—driven by agricultural productivity and topography—is almost blind to stylized historical facts that would tend to bias it toward the actual paths of agglomeration and fragmentation; thus its ability to produce European fragmentation and Asian integration along Diamond-esque lines (and for the same reasons) is telling.